Music in Cuba

The Cuban musical panorama is very interesting. There are many people, especially young people, who are doing good things and taking risks. The country opened up quite a bit to information. And it has done so from the outside in, but also from Cuba to the world.

We are in a time of great need, above all economic need, and some people want to get into the market, make a splash and be an overnight success. That way they’d acquire another means of income. Some of those people don’t care as much about artistic quality as about the numbers—views, likes, etc.

There is a group out there that’s on top of that type of dynamic, but there is another group interested in using these Internet tools to show the value of our music and culture. If you ask me, Roberto Fonseca, I am convinced that the latter is the way to go.

The Cuban Cliché

Cuban culture is very rich and it’s respected world-wde. Nothing bothers me more when I’m outside of Cuba than people who say to me: “You’re from Cuba? How great—women, cigars, and rum!” Well, look, I don’t drink rum. Someone always says jokingly to me, “ah, then, you’re not Cuban.”

Some people treat us a certain way because there’s a market interested in showing only positions contrary to what happened in Cuba after 1959. Many times that market does crude things. I’m not talking about if the music is bad. I’m talking about responding to a certain interest.

By going in another direction, I am very involved in Cuban jazz festivals. I am the musical director of the Jazz Plaza Festival and the president of the Santiago de Cuba Jazz Festival. My hope is not only that the audience listens to the international guest artists but that they listen to the Cubans and hear everything that is produced here in different genres and styles.

I’m not the only one with that goal. Chucho Valdés is the best Latin jazz musician. He had all the tools, he put them on the market and he was instrumental in getting Cuba to the place where we’re at today. Chano Pozo and Dizzy Gillespie were the creators of Latin jazz, but Chucho took it to the level of saying, “I am Cuban and in Cuba all these things happen, we have this jazz, this musical history.”

Reggaeton, and How to Talk about Culture

I am one of those people who are opposed to criticizing reggaeton. Just like with trap music, this genre has, from the sound point of view, an incredible rhythm, it’s super contagious.

The problem, it’s true, is in its lyrics and its video clips. But it’s important to note that the popularity of this genre is because a certain audience responds to it.

It’s not a topic just for criticizing reggaeton. It’s more about how we “talk” about culture. If you live in the house of rock, and I want to talk with you, I can’t tell you “rock is rubbish, the truth is traditional Cuban music.” On the contrary, if I want to converse with you, I should say: “Look, I’m going to bring you some of the rock you listen to, but from my point of view.”

All music is interesting. I have no problem with making trap music, but I don’t want to lose the essence that is central. The point is that we cannot converse with a closed mind. We must converse with an open mind.

Roots and Tradition

There are musicians, including myself, who are working on our roots. A song like “Afro Mambo” is one example. If you put on a mambo everybody dances to it, but it’s not played frequently. My goal is not to “rescue” that music—because it hasn’t been lost—but to bring it to the present day with my way of seeing Cuban culture, and the world of today.

I was lucky to enter a real traditional music school. I’m referring to all the musicians that convened around the Buena Vista Social Club project. You’ve reminded me of the controversies over this endeavor and how some authors have argued that perhaps it was part of the exploitation of a certain market nostalgia for pre-1959 Cuba, but I will tell you what I experienced there from the inside.

I’m being honest. It’s true that to make a product that you want to sell in the market, you have to create a story. You always have to do marketing, and there are markets that exploit the Cuba of yesteryear, as well as others that do the same with post-revolutionary Cuba.

Trends arrive, and displace others, even though they have had good and lasting moments. However, that story wasn’t made up. They were doing what they liked to do. I never saw them trying to sell a nostalgic Cuba. Nothing like that. At the concerts, politics was never discussed. We went on stage and it was always a party, given what they knew how to do, because in large part it was what they had created.

Although I began after the Buena Vista boom, each concert was still an event. The shows were completely sold out more than six months in advance. Ibrahim Ferrer, in particular, didn’t know how to “dance” as it is usually understood that one dances here. He had his little movements, his style, but I swear to you: when he sang and acted he was literally Michael Jackson before that audience.

I fed on that. They were jokers, but they lived for music all the time. That’s where I heard their stories, which allowed me to understand why they thought the way they did and why they did what they did. I’ll go even further: it’s a whole philosophy. They played like that, because they thought in a certain way.

Popular culture and academic culture

Popular music is a label. When we mention it, we run the risk that Chaplin summed up like this: “where there’s a jury there’s an injustice.”

Classical music can also be popular. It is not easy to define something as popular music. Right now reggaeton and trap are very popular. Now, if you’re talking about traditional music—María Teresa Vera, Miguel Matamoros or Arsenio Rodríguez—it’s very complex music.

Its complexity lies in the transparency with which it is interpreted. It sounds easy, but it is not. I made that interpretive mistake. When I was in school, I liked it, but I said “that’s easy.” It seemed like just a couple of tumbaíto rhythms, and I was looking for other depths.

By the way, let me tell a story. When I was getting into Buena Vista, we were going to record an album by El Guajiro Mirabal. When we came to the song “No me llores más,” by Arsenio Rodríguez, they said: “let’s listen to the song first.” At that moment, that’s when they gave me the sheet music. I looked at it and thought, “well, this is easy.” Suddenly, in the original recording, someone said “Arriba Lilí.” And then came Lilí Martínez’s solo.

It is the most amazing solo that you can hear in the history of traditional Cuban music. I simply prayed that they wouldn’t make me do it. Call it whatever you want to, but there is a something out there that listens to you. It heard me. I was convinced that it would be the biggest humiliation of my life if I had to play that solo. But, look, the thing is that I had graduated from classical music school, I was a professional, I had gone head to head with many greats in Cuba and in the world, playing jazz. And I listened to that song, which had two chords, played by an amazing pianist, and there I was, praying not to have to play it at that moment.

Popular music is responsible for a very important problem that always has philosophy in the background. It means understanding this: I have this thing inside me, it’s beautiful, I’m going to share it with you and it will go straight to your heart. It is much easier said than done.

Cuban Music and the Afro-Cuban Heritage

For me, Cuban music is everything. The jazz we play is Cuban jazz. But to be Cuban music it must have the clave and tumbao. The cliché with Cuban music is that it has to be dance music or son montuno.

There are many ways to make something sound Cuban. For me everything that comes from Cuba, is made in Cuba or is made by Cubans, is Cuban music.

For me, recognizing myself as black is everything. Thank God I’m black. That awareness gives you many things. Many mistakes have been made about people who have this skin color. We also have to recognize that we have made mistakes. We have not only been victims. For example, there is a racism exerted by blacks themselves.

But I am not one of those people who say, “if you aren’t black you can’t understand this.” We are all the same, we’re all human beings, whether we think differently or not, but I don’t make my skin color a flag. For me it is an awareness, a matter of rights, and a culture. It is not a flag with which to crush someone and say, “you can’t understand rumba because you are not black, because you don’t have it in you.”

The same, on the contrary, can be said about the kind of sayings like the one I heard in school about myself. They told me that I was black on the outside but white on the inside. Actually, I feel super proud of being black and I try to make sure that all that culture, all the Afro that is in me, is in my music. The word Afro-Cuban explains what I am. I do not consider its use as a copy from the United States or any other place. My music is Afro-Cuban music.

Creation and Innovation

When you create something you can go through everything. You can spend years playing in some “lost” place somewhere, which happened to Bebo Valdés, but you always sound like the first time. That’s why traditional music, as Bebo played it, always sounds pure. It was something he created. There is no copy in it.

Bebo has his stamp. So do Chucho, Lilí Martínez, Rubén González, Peruchín, Emiliano Salvador. They created a style. In jazz, you can find this with Miles Davis. He can go from one style to another, but you always know it’s him. In Cuba, this also happens with Manuel Galván.

It’s very difficult to innovate. Music has a long history and it has patterns. It is not about composing something and saying “I am the creator of this thing.” To do so, you need a lot of preparation and knowledge. You have to master what you are doing and know a lot about what you think you are going to innovate on.

Now, there are those who are born with a gift, who without having all the training, all the knowledge, are capable of creating. They have the talent to do something different. In any case, daring is essential, the risk of breaking with patterns. It is not enough to just have preparation, knowledge, talent. One must also have the courage to face all the risks involved in the process.

When Astor Piazzolla started doing his thing they said he was destroying music. The same happened with Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk. Now Monk is considered a very revolutionary pianist. Same thing with Arturo Sandoval. It’s just that they were moving with codes that people were not used to listening to. Human beings, when faced with something unknown to them, tend to feel fear. And the normal response is criticism.

The market generates many problems with quality and with tradition. Unfortunately, it is what has made people play in a certain way. People want to eat and they don’t want to struggle every day by trying to do something new.

The Things I Believe In

I don’t like injustices. I don’t like that human beings try to destroy other human beings. It’s something I despise. I don’t like to impose things either. As long as something doesn’t affect you, don’t disrespect, don’t attack, everyone should let everyone else do their thing. I respect everyone who struggles to create something they believe in.

I feel a deep pride in the culture of this country. I believe that the musician-producing factory is one of the ones that is still working well in Cuba. I’m not talking about logistics, infrastructure; I mean the artistic creation itself. Cultural creation must be free, but I also believe that we must be careful not to hurt sensitivities. It’s a subject that depends on the interests, spirituality, information, culture, of those who must make judgements about that creation.

Being a musician makes me a privileged person. The world we live in grew out of vibrations. What I do produces vibrations on several planes. A very important one is moods: music makes you suffer, cry, it makes you happy, it produces sensations. However, not everything is joy. The musician who decides not to be behind a lectern, but rather tries to be at the vanguard, will almost always have a tough time.

It’s not about you becoming a slave to the market. If you believe in what you do, and what you do is pure, you will always make it. I am talking about the “purity” of the place where what you do is born, the quality of your emotions and your commitment. It’s like life, with its ups and downs. You have to be smart: when you’re on the downhill, you have to learn from the fall, from the things that push you down, and then load yourself up with information and emotions, and then, when the time comes for the climb, walk with that experience and that baggage.

But it is important to always remember this: he who decides to have a voice of his own will almost always have a hard time. It is your decision and the consequences are yours.

SOLO DISCOGRAPHY

Tiene que ver (1999); Temperamento: En el comienzo (1999); Roberto Fonseca: No Limit (2001); Roberto Fonseca: Elengo (2001); Roberto Fonseca: Zamazu (2007); Roberto Fonseca: Akokan (2009); Enja Records Roberto Fonseca: Live in Marciac (2010); Roberto Fonseca: Yo (2012) Nominated to a Grammy in 2014 in the category of Best Latin Jazz Album; Roberto Fonseca: Abuc (2016).

COLLABORATIONS

Black P. Marabal Bandasonora (2000); Cuando yo sea grande –Augusto Enríquez– 1998 (Egrem); Cachaíto –Orlando Cachaíto López– 2001 (World Circuit Records); Felicidad –Asa Feeston– 2002 (Inter Records Co Ltd); Buenos hermanos –Ibrahim Ferrer– 2003 (World Circuit Records); Guajiro Mirabal –Guajiro Mirabal– 2004 (World Circuit Records); Flor de amor –Omara Portuondo– 2004 (World Circuit Records); Angá Echumingua –Angá Díaz– 2005 (World Circuit Records); Javier Zalba –Javier Zalba– 2006 (Colibrí); Timbalada –Carlinhos Brown– 2006 (Candyall Music); Mi sueño –Ibrahim Ferrer– 2007 (World Circuit Records); Absolument Latino song Zamazamazu 2007; Gracias –Omara Portuondo– 2008 (Montuno / Harmonia Mundi), Latin Grammy Award; Omara & Maria Bethânia– 2008 (Biscoito Fino); Etxea –Kepa Junkera– 2008 (Warner Music Spain); Gilles Peterson presents Havana Cultura New Cuban Sound– 2009 (Brownswood Recordings); Gilles Peterson presents Havana Cultura Remixed– 2010 (Brownswood Recordings).

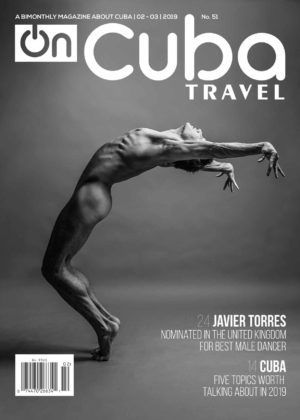

This interview is included in the 51st Edition of OnCubaTravel Magazine: