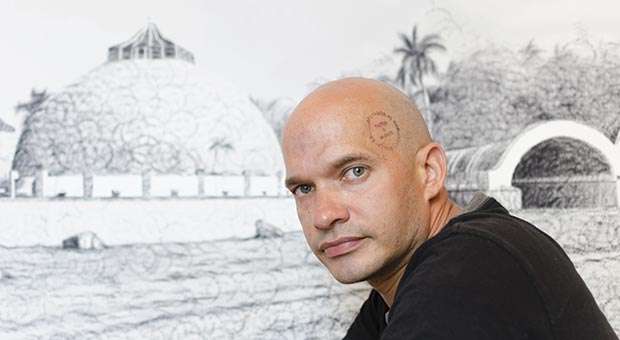

If there is anything that distinguishes the work of Kelvin López, it is the diversity of his styles: it’s as if his hands multiply—into several pairs—and form a set of images organized into perfectly differentiated series. “I don’t always want to be the same artist, and my interest in not having a style can become a style,” he said.

The young painter and engraver comes from a family where art and science converge: his mom was a math teacher at the School of the Arts, and it was perhaps from her that he inherited “a sense of analysis and rational thinking.” His brother, Kadir, is also a well-known artist (both brothers “snuck” into the academy’s workshops from a very young age). And his father has an innate capacity for correctly solving practical situations, along with many wonderful manual abilities. That context, Kelvin says, was the “motor force” of his development in the world of pictorial creation.

He was born in the eastern province of Las Tunas and admits that coming to the capital was a shock: “The ISA (University of the Arts) is an essential place for understanding creation from a different standpoint, and it was a gift that life gave me for five years to be totally free,” he says.

In his attempt to “stir up his own creative structures,” Kelvin believes that landscapes are his mode of expression, but he approaches them differently, trying to solve the same problem from different angles. It is like approaching, or outlining, a single idea in diverse ways, which is why he structures his work in series: Fantasmas zodiacales (Zodiac Fantasies), Tormentas (Storms), Plein Air, Arriving, Islas (Islands), Amigos comunes (Common Friends) and Achievements.

Fantasmas zodiacales plays with the idea of a lack of control over certain situations; Tormentas, devoted to the effects of hurricanes that have hit Cuba, captures the moment in which the country stands still and what has been lost must be recovered; Plein Air, is a tribute of today to the open air painters, a very well developed school in Europe that was born from landscapes that arrived via email, and which constitute a global connection, passing through the filter of technology; Arriving is a landscape that is more psychological than physical, a reencounter with family, with your place, and at the same time, very social, because every Cuban has a relative somewhere else in the world, and the issue is a constant one for Cuban families; Islas is centered on nostalgia, and revisits the island phenomenon from the standpoint of how to go or how to arrive; and Amigos comunes is a series of drawings that talk about how globalized children’s fantasies can become.

At this time Kelvis is very focused on the Achievements series, and he is using phrases and slogans that defined the revolutionary early days in 1960s Havana. Phrases, converted into seals, are utilized as tools for drawing specific scenes and contexts from the Cuban capital, where yesterday and today reorganize our perception of our surroundings and redefine social and cultural schemas. In other words: using photography, Kelvin reproduces the facades of homes that were abandoned by their owners when they left the country and that became senior citizens’ homes, clinics for children, childcare centers, etc.: “The Revolution that was faced by the country on a social level is a phenomenon that has always struck me, and that’s why I insist that Achievements is a temporary record,” he explains. Visually, it is very attractive, because using the seals makes it possible to use an engraving approach, and the work itself becomes a mold. Achievements, Kevin says, is a “return and a reencounter with its formation.” And that is true.

Kelvin’s work oozes intimacy, something that characterizes artists who tend toward introspection and constant personal review: “Sometimes, we are very selfish and we have an inner world and a personal relationship with ourselves that makes us so different and strange for common mortals. I recognize that I am a real homebody, and my connection to my own work is visceral.”

He defends the idea that conceiving a painting involves a lot of mental process, because meditating on “how I’m going to solve the work and begin to produce it is all very conscious. I never start something without knowing what its end will be, and even though I don’t do sketches, I am totally sure about where I want to go with it.”

Convinced that “you won’t be an artist if you copy or seem like someone else,” Kelvin continues digging, scratching, and immersing himself in that “other landscape” that he has set out to capture, because—he says—“if you aspire to be a solid artist, your work has to have unique conditions and characteristics that are the fruit of individual development. The formula has to be personal, and cannot exist in parallel. I think that is the key to success: to be yourself.”

And that element of not being like anybody else is, perhaps, one of the most personal keys to his work, to the style without style of Kelvin López.

Kelvin López (Las Tunas, 1976). Graduate of the University of the Arts in Cuba in 2000. Since his first solo exhibition, titled Who Dared to Look at the Cuban Landscape (1992), he has shown signs of a leaning toward landscape painting as a form of expression. Kelvin’s work is in various museums—Arizona State University Art Museum, Phoenix; Amistad Foundation, New York, and MoLAA (Museum of Latin American Art), California, all in the United States—and he has held solo shows at the Michael Connors Gallery in Manhattan; the Spence Gallery in Toronto, the Eye Lounge and Down Town galleries in Phoenix, and many more.