When Fernando Ortiz differentiated the Cuban condition―cubanidad and cubanía―he did not establish ideological distinctions. And when he spoke of belonging to a culture, inside and outside the island, it was not limited to the taste for sleeping black beans or not being able to control the movement of the waist when hearing certain irresistible beats, but to the self-awareness and the will to remain as part of a real community, not only evoked in phrases and images, which claimed its Cuban identity.

Here, however, we don’t find all the answers, but rather the path of difficult questions begins. When some propose to place the Cuban condition as something superior to differences and interests, “with all and for the good of all,” and other Martí quotes, and declare their adherence to “the nation,” they are opening a Pandora’s box which, far from verbally solving the equation of national unity, complicates it.

Of course, among the landowners and bankers, and other partners of American capital and their employees, who began to leave the island since 1959, there were Cubans of a certain cubanía. So were those representatives of the Batista dictatorship or even that of Machado. In the same way that the Third Reich and the Krupp family were unquestionably German, with their own awareness of national interest and Germania. Since cubanía or Hispania do not involve any civic or moral condition, much less ideological, nor a single and common nation project. (When in doubt, ask the “Spaniards” about what defines the Hispania, and see what they say.)

The big owners and segments of the Cuban upper middle class, who were leaving the country until the October Crisis ordered the stop of direct flights, with the hopeful certainty that the U.S. government would resolve the headache of Castroism, were not only bearers of anti-communism, but they had a certain political culture. There was no simple ideological loathing in them, but rather powerful and very concrete reasons to leave.

The same happened to all those who, having opposed the Batista dictatorship, reacted to the measures of social justice of the revolutionary program, from the Agrarian Reform onwards, turning against them. For them, the changes were not only too radical, but alien to “their revolution,” which they declared had been betrayed, kidnapped by “the communists.”

This reaction, unleashed even before the Soviet Union understood what was happening in Cuba, where the Popular Socialist Party still spoke of “the January revolution,” set off a formidable counterrevolutionary force, which spread throughout cities and fields across the country.

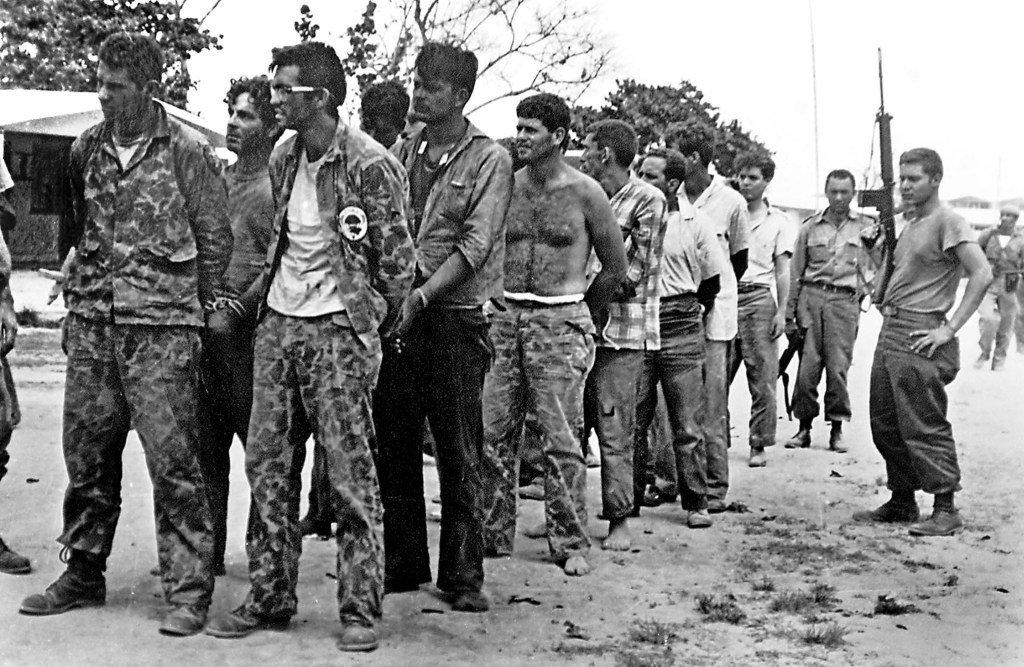

With the unrestricted support of the upper class and the United States, and encouraged by a kind of visceral feeling generically identified as “anti-communist,” rather than by a coherent ideology, that current, just in the rural areas, led to arms almost 4,000 counterrevolutionary insurgents, who got to cover all the provinces of the country.

Their military defeat was achieved only after five years of a stubborn civil war, which survived the Bay of Pigs and the October Crisis, and even the rise of undercover operations of the United States government known as Operation Mongoose.

That war, whose complex social and political fabric has been documented in just some published research (and tangentially, in a recent Cuban television series), would leave a national security mark on the island’s immune system that would condition the treatment of emigration in later years.

The survivors of that civil war went to nurture a recalcitrant exile, which fed paramilitary groups for decades, less and less effective in overthrowing revolutionary power, although they did harass it and made it pay a price.

Constituted as a modus vivendi, these Cold War hardliners symbolized the unyielding spirit of an exile that had a hard time recognizing their defeat. However, an increasing number of those who once set out to fight with weapons, deep down inside already knew that their status as exiles or refugees from communism had become permanent.

Decanted and quintessential in that cystic exile, and subjected to the frustration of all their hopes, the old political culture of the expropriated class and its former army was distilled into an exile’s kind of Bacardi, which permeated the cultural codes of emigration, not only within the scope of that powerful elite that had come down in the world, but also outside the country.

The intransigence and the indistinct rejection of everything that smelled of “Castro’s Cuba” has been the password to that distillation.

I remember that when a young Cuban-American woman, a descendant of a family of renowned bankers, who had been my student at an American university, invited me to eat with her family in Coral Gables, her mother decided to leave the house, claiming that she couldn’t share with “one of those who had stolen my parents’ properties.” It was no use for my student to tell her that I was twelve when they had nationalized that bank, since for the lady I was as responsible as Fidel Castro himself.

However, not everyone who went into exile in the 1960s shared an active militancy. Since the Cuban Refugee Program inaugurated by President Kennedy in 1961, many who had no link to the organic counterrevolution chose to send their children to the North so “they wouldn’t be brainwashed” or “sent to the Soviet Union.”

Many others, also disconnected from that active opposition, decided to flee the economic hardships and the cost of the isolation of those years, and accepted Kennedy’s invitation to share the American dream, including exceptional privileges and advantages, which not even those who had previously escaped from the “iron curtain” in Europe had enjoyed.

When the Cuban government forced the signing of an immigration agreement, the first, through the opening of the port of Camarioca, near Varadero, in 1965, more than 300,000 aspirants to get out of the siege to which the island was subjected in the middle of a hostile hemisphere, took advantage of the occasion.

So, when Nixon canceled the agreement and the airlift, in 1973, not only those who had waited since October 1962, but a growing segment of the lower middle class and direct workers, many of whom responded more to family reunification and scarcity than to ideological motivations, had left.

All that heterogeneous group of new migrants had in common with those who had left before the common condition of not being able to return. Unlike most of the exiles in the world, Cubans entered a permanent refugee status, in which they would remain from then on.

As is known, the first scratch in that perfect glass of anti-Castro exile occurred when the Cuban government issued an invitation to a dialogue, in 1978-79, where a very heterogeneous group, in which there wasn’t a lack of veterans of Brigade 2506, paramilitary operators, conspirators of the Catholic organizations, bankers and youths taken by their parents when they were minors, met with Fidel Castro in person.

This scratch on the supposedly homogeneous mass of the exile, would impose an equally sudden 180-degree turn within the island: the “worms” became butterflies, that is, “the Cuban community abroad.” The phrase that sealed that dialogue, just two years after a Miami-based anti-Castro paramilitary group attacked a Cubana de Aviacion civilian aircraft in full flight off Barbados, was said by him, as if to crown the bold turn of that policy: “The homeland has grown.”

Among the many causes and hazards of Mariel, the most extraordinary migratory explosion of all these years, a few months after that phrase, was not a counterrevolutionary rebellion or an economic crisis, but the simple notion that, after all, the door was no longer so closed for those who were leaving. And that it was possible to overcome the accumulated rage and the legacy of resentment, the culture of the predominant exile there, and even the intact revolutionary combativeness (as it would be demonstrated in 1980), to maintain the spirit of good will and conquered coexistence.

The return of the new “community members,” and the beginning of family reconciliation, was not enlivened by any mea culpa, hint of triumph, revanchism or reproach, but by the mute language of suitcases loaded with gifts (hitherto prohibited by revolutionary ethics), a supposed reflection of their standard of living and consumption status in that country.

In the typical way of those Spaniards, who returned to the motherland telling the stories of their splendid life in the hacienda they owned in New Spain, the emigrants, conveniently stripped of all the stripes of exile, returned in peace and harmony. Subsequent studies would show that their level of indebtedness with Miami banks had skyrocketed since 1979.

That reunion, however, would not be free of antagonisms. On the Miami side, the standard bearers of exile declared war―and this is no metaphor―on the “dialogists.” On this side, despite Fidel’s enormous authority and convincing ability (in a very long speech at the Karl Marx theater addressed to the members of the Communist Party of Cuba), many good revolutionaries confessed in private that it was not easy to swallow that 180-degree political turn they were chewing.

All that was there when, in the middle of the 1979 and 1980 thaw with the Carter administration, the Peruvian embassy crisis broke out. What came next, the Mariel crisis, was already another chapter in the history of emigration and exile.