|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

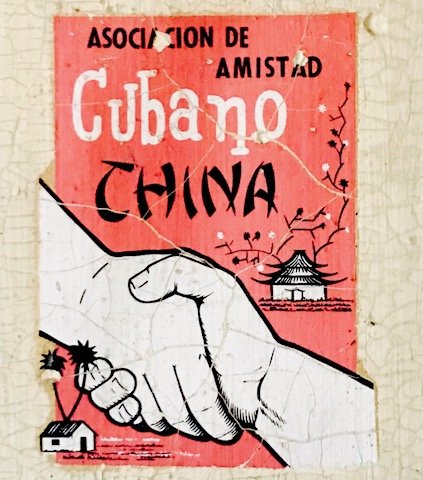

Now that China (and Vietnam) have become political debate referents in Cuba, taking a look at the ups and downs in relations with the People’s Republic and its presence in the Cuban process could contribute to a more enlightened debate about their real meaning.

After the Chinese invasion of Vietnam (1979), as a result of the Vietnamese intervention in the Kampuchea of the Red Khmers, and the heated political confrontation that this provoked between the governments of Cuba and China; the end of the conflict in Southwest Africa (1988), where both socialist nations aligned with opposite political actors; and the advance of the post-Mao and post-Deng transition (1989), bilateral relations would begin an upward turn, which would take them to their highest level since the early 1960s.

The echo of those ideological and political disagreements would still resonate, however, 20 years after the collapse of the USSR, when Cuba had already launched the Updating of the Socialist Model (6th Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba, 2011), and 15 years after Deng Xiao Ping’s death, when Fidel Castro last remembered him in his “Reflections” (June 14, 2012): “He boasted of being a wise man and, undoubtedly, he was. But he made a small mistake. ‘Cuba must be punished,’ he said one day. Our country never even mentioned his name. It was an absolutely unwarranted offense.”

This kind of epitaph, which many Cubans who didn’t know about its antecedents did not understand, reflects the contradictory and very complex nature of relations between the two countries, which is often simplified.

Some illustrious historians of the Cuban economy have called the second half of the 1960s the “Sino-Guevara stage,” as if what really happened in economic policy was then explained by the influence of Mao or the very Che, supposedly a “Maoist” (who was already outside Cuba in 1965). On the contrary, according to others, Cuba’s differences with China are explained by its alignment with the USSR in the dispute that separated the two socialist powers. For this vision, the nationalization of almost 60,000 small businesses during the Revolutionary Offensive (1968) responded to the influence of Stalinism; and even the very state-centered conception of socialism was only its ideological reflection in the Cuba of that time.

According to all aforementioned, the errors or excesses of Cuban politics were due to the fact that, in those 1960s, Cuba had aligned itself (simultaneously?!) with a concept of socialism typical of China’s Great Leap Forward and Stalin’s Marxism-Leninism. This peculiar account ignores Fidel’s public disagreements with Mao (since 1966) and with Soviet politics and ideology (since 1962); and seems to be unaware that the Offensive took place just three months after the trial against a pro-Soviet group from the old Popular Socialist Party (called the Microfraction), in which the embassy of the USSR had been involved. It is also inconsistent with the open Cuban opposition (Fidel and Che) to the Sino-Soviet discrepancy, and the pressure on third parties to become customers of one or the other.

Understanding Cuba’s relations with the two socialist powers requires not only placing them in the polarities of the Cold War, but a fourth leg: the Third World. Since then, it represented a strategic axis, which Cuba saw as essential to balance the enormous geopolitical asymmetry with the United States, as well as to build a space of autonomy in its necessary, although not sufficient, alliances with the USSR and the People’s Republic of China.

Access to declassified documentation from the Tricontinental Conference (January 1966) provides a high-definition view of Cuba’s real relations with these two powers, both present at the meeting, and participants, through their “non-governmental organizations,” in the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL).

For Cuba, the project to build the OSPAAAL faced several problems, especially the concertation of a common agenda, and reducing the impact of the Sino-Soviet discrepancy, especially its multiplied effect on the states and political organizations of the three regions. According to Cuban domestic reports, the two great socialist powers had turned the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Asia and Africa (OSPAA) into an “arena of confrontation,” whose course inclined to one side or the other as the majority aligned with one of the two, as well as in a “bureaucratic, inept and ineffective structure for national liberation.” Thus, the United Arab Republic (Egypt) under Nasser was typically aligned with the USSR; meanwhile, Pakistan and North Korea did it with China. African states, for their part, associated themselves with one or the other according to the situation, and in many cases they were followed by national liberation movements,

The Cuban strategy in the arduous process of the creation of OSPAAAL consisted in negotiating bilaterally with key actors, including the big ones (USSR, China), the middle ones (UAR/Egypt), and the small ones (Africans and National Liberation Movement), as well as with allies (Democratic Republic of Vietnam, South Vietnam, Laos). Along these lines, Cuba would be forced to deploy flexible diplomacy to win the support of pro-Chinese (Indonesia) and pro-Soviet (Guinea) countries.

Although some interpreters by ear of Cuban politics still identify those years with “the shooting stage,” the main Cuban objective in this tricontinental meeting was not support for armed struggle, but an alliance against imperialism, colonialism, neocolonialism; and the reaffirmation of an agenda of peace, disarmament and peaceful coexistence for all, not only the great powers, as the Non-Aligned Movement had advocated since its founding. It was also, of course, getting support to achieve and defend national liberation.

But this concept was not reduced to the armed struggle or the differences that arose in the Tricontinenal debate around it revolved around accepting or denying it. These debates only reflected the reluctance on the part of some organizations and governments to adopt a position that excluded other forms of political struggle. In fact, numerous movements identified with national liberation, which did not advocate guerrilla warfare, participated in the founding of OSPAAAL, such as those represented by socialists Salvador Allende (Chile), Heberto Castillo (Mexico), John William Cooke (Argentina), Cheddi Jagan (Guyana), or by the delegations from Uruguay, Costa Rica, Honduras or Haiti, just to speak of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Because of all the above, the differences with China and the USSR were neuralgic for the central question of unity, in a movement characterized by its very diverse and plural composition.

This quick and incomplete look at some aspects of Sino-Cuban relations is just a sample, or rather, the tip of the iceberg, in a history of understandings and misunderstandings in the making.

While that history is being made, it is necessary to advance in a more substantial understanding of politics―Cuban, Chinese, everyone’s―that goes beyond the rule of common places. Identifying the analysis of politics with its ideological contents, reducing those contents to a philosophical doctrine such as Marxism-Leninism, and putting everyone with a single party in the same bag of communist political systems, doesn’t allow for understanding it in perspective, in particular, to appreciate the nature of past alliances and divergences between Cuba and the two socialist powers, or, let’s say, neither the current discrepancies between Vietnam and the People’s Republic of China.

Nor, by the way, does it allow for understanding that the normalization of these socialist regimes’ diplomatic and commercial relations with the United States doesn’t derive simply from having begun a process of reforms, which has not advanced enough in Cuba. Both China and Vietnam followed their own route, motivations and interests for this approach, not without tension, and very different from the conflict that separates the island from its neighbor. The political reasons and logics that led Nixon (1972) and Carter (1978), as well as Clinton (1996) to normalize relations with the People’s Republic of China and with Vietnam were not created with the Reform and Opening or the Doi Moi.

On the other hand, however, it is worth asking to what extent the Cuba-China-U.S. triangle, in an enlarged picture of their current interrelations, has significance for the two powers, and also for the outline of Cuban foreign policy.

To conclude, of course the end of the USSR and the African wars, the crisis of the Special Period and its consequences, the successive change of the Chinese leadership, and also of Cuba’s, are part of the context of the Sino-Cuban rapprochement, which started what a Chinese newspaper called a “completely new and constant period of development,” and has turned the People’s Republic of China into the island’s first trading partner.

It is also evident that, for Cuba, updating the socialist model does not simply mean catching up with China and Vietnam, but evaluating past practices, in order to formulate new ones, including citizen participation, expansion of the public sphere, institutional revitalization, and especially, take advantage of its own social and cultural potential. To what extent do these other features bring it closer to or distance it from particular historical experiences, inherited cultures, social structures, demographics, geopolitical and geoeconomic contexts, in which reform processes take place in China and Vietnam, is key to interpreting the lessons that all three can learn, both in their successes and in their mistakes.