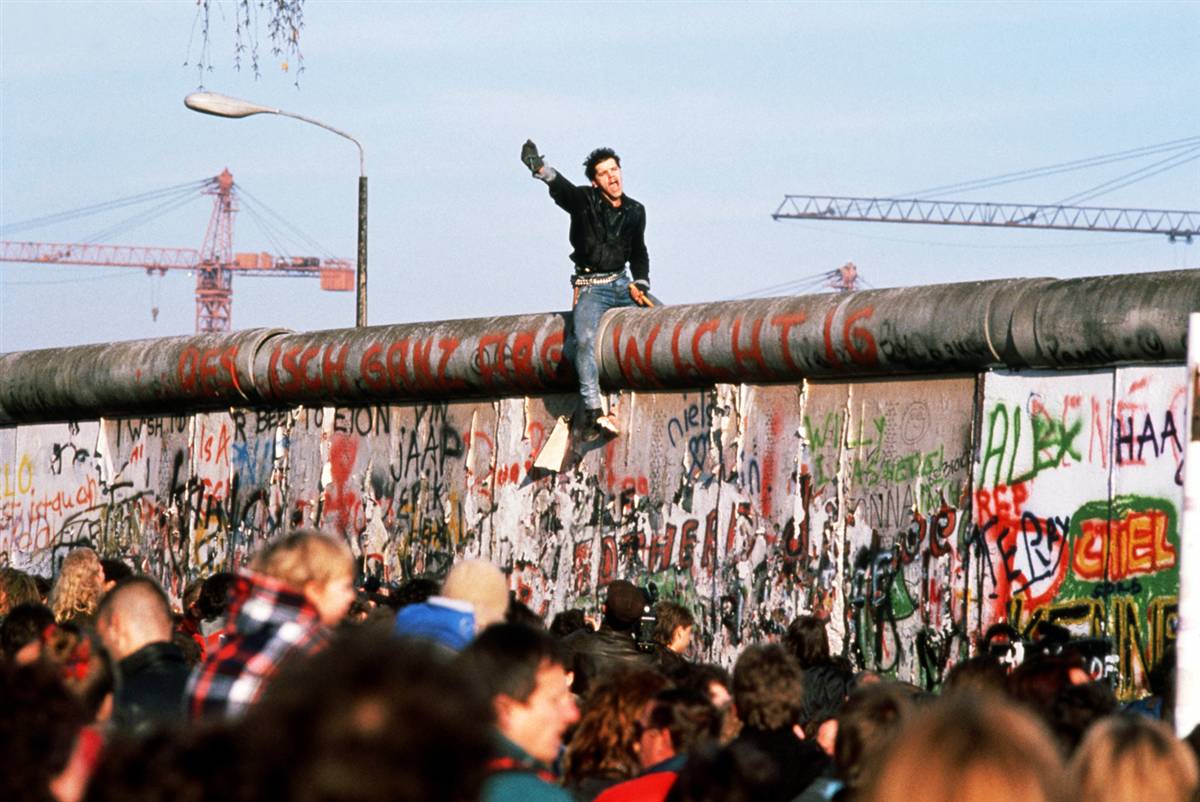

The fall of the Berlin Wall (November 9, 1989) and the disintegration of the USSR (December 26, 1991) fueled in the United States a kind of in crescendo in public information about Cuba. Expectations were built around this platform regarding the possible evolution of internal events in a context of economic and social crisis with deep repercussions that continue to this day. Socialism on a single island? For how long? Could Cuba survive the disappearance of Soviet subsidy? Peaceful or violent transition?

The above were, basically, the big questions planted in politics and the media at that time. In its answers, the predictions about the duration of the Cuban regime were usual, which, if generous, came to grant it only a 50-50 chance of survival in the new century. A strongly negative image about the socialist system was reinforced then, built on the general consensus in politics and the media, granting it little space for alternative points of view within the mainstream. This in turn led to the idea of celebrating Christmas Eve in Havana or predicting that Fidel Castro would fall three months after the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (LIBERTAD) Act, better known as the Helms-Burton Act, was approved by the U.S. Congress (1996).

In this context, there was an overestimation of the role of contacts with the West in the events of Eastern Europe, since, according to this logic, what worked there would inexorably work in Cuba, a card that was bet on in reports, recommendations and the media. That is where the so-called “track two” emerged, understood as a way to get rid of the prevailing system through the logic of contacts: in Cuba it was characterized as “the kiss of death.” “We are trying to open more communication channels,” said a State Department official in the Clinton administration. “We expect that what is seen in Eastern Europe will help refresh the island’s society. We are trying to help the Cuban people for when the inevitable transition occurs.”

Seen in retrospect, perhaps one of the most vulnerable points in the entire process of rearranging the image was to present Cuban culture as a closed culture without interactions with external dynamics, precisely in a context characterized by the multilateral relationship with the world, not only from tourism and foreign investment, which in 1993 began to make their way in Cuba as part of an agonizing process of adjustments and reforms, which has shown, to date, more resilience than progress.

But the idea of isolation had a powerful support in the construction of the image: Buena Vista Social Club (1997). Captained by the Beach Boy Ry Cooder and Cuban Juan de Marcos, the producers of the CD and the homonymous film by Wim Wenders (1999) recycled a group of past musicians, oblivious to any sense of modernity even in the instruments they played, an ideal force to prop up the image of a country where neither McDonald’s nor Coca-Cola advertisements are part of the visual horizon. In that atypicality lay its power of convocation, that is, in the idea that globalization, supposedly, had not appeared in Cuban lands, even at the level of the media in which that wonderful music sounded, but stopped in time, well away from electronics and synthesizer sound.

And along with Buena Vista came two correlates, the first painfully real: the image of a Havana ruled by ruins and old cars, converted from that moment into what tourism experts call “a brand.” But, in all cases, one thing was clear: the Cubans were a dark smiling people waiting for a new Rudyard Kipling photographer.

The case of Elián González (1999) constituted, as before those of Lorena Babbitt, O.J. Simpson and Monica Lewinsky, a kind of national obsession in the United States that put the pre-eminence of Cuba and Cubans from both shores in the United States on the agenda, in public spaces, in everyday conversations, workplaces and home kitchens. It was a complex matter, where not only the fate of a minor claimed by his father was at stake, but also the problem of values and the right to custody, the latter of lacerating importance for American society, given its high divorce rates and litigation associated with the problem of who gets to keep the children after the breakup.

After the events of September 11 (2001) and the passage of Hurricane Michelle (2001) through the United States, there was a specific event, but unprecedented since the enactment of the blockade in 1962, which, however, did not mean the dismantling of the current scheme: Congress authorized the sale of food, medicine, and agricultural products to Cuba, which once again gave the island important coverage in the media with the subsequent debate about the rationality or not of the framework applied in relations.

Later, the transfer of Afghan prisoners and those of other nationalities to the Guantanamo Naval Base, and the lines of communication maintained in this regard between the Cuban and U.S. military, placed the island in an unusual public visibility, perhaps as it had not had since the time of Ethiopia and Angola.

As was to be expected, the opponents of any rapprochement recorded their position by highlighting not only the previous events, but also after George W. Bush postponed for the second time, since the beginning of his term, the application of the Title III of the Helms-Burton Act, for which — among other things — a sector of the exile had accused of being a communist Democrat William Jefferson Clinton, a former governor of Arkansas who had defeated George Bush (Sr.) despite high rates of popularity gained by him during the Gulf War.

The truth is that at the beginning of the new century all this accumulated temporary situation led to what some called then, with good reason, “Cuban fashion” in the United States. “Cuba is in fashion. Cuban things are fashionable and in vogue” — confirmed the prominent Cuban-American historian Louis A. Pérez, Jr. — “Cuba is way too cool,” declared singer Bonnie Rait after an experience with Cuban musicians, who met in 1999 at the Hotel Nacional de Cuba for a jam session at the Music Bridges event, in which artists such as Burt Bacharach, Gladys Knight, James Taylor, Jimmy Buffet and Mick Fleetwood, among others, participated.

On the other hand, the visit to Cuba by former President James Carter in May 2002 had the effect of recycling public perceptions of the island in the mainstream media and, above all, on TV. From this angle, what was distinctive was the public emergence of the existing debate among sectors of the U.S. political class about how to deal with Cuba. Both inside and outside the media, “doves” and “hawks,” as usual, differed in methods, but there was a coincidence in purpose: President Fidel Castro had been in power for too long and politics had failed to get rid of him, something that had to be corrected after more than four decades. Thomas Shannon, undersecretary of state in the George W. Bush administration then (again) predicted the imminent end of the regime. “Authoritarian regimes are like helicopters. If the rotor fails, you fall,” he said. “When an authoritarian leader disappears from an authoritarian regime, the authoritarian regime falters…. This is what we are seeing at the moment.”

At that very moment, Cuba’s image of bête noire reemerged, this time with the idea that it would have the potential to produce bioterrorist weapons against the United States, a construct formulated by former Undersecretary of State for International Organization Affairs, John Bolton, in the Heritage Foundation, a think tank that had served as one of the ideopolitical bases of Reaganism.

That idea did not prosper much, but it was clear that the “hard” sector was blocking its mechanisms of public opinion in order to maintain the status quo, appealing to the very sensitive issue of terrorism after 9/11.