Arriving at the other bank of the river, the U.S. military were right there; they saw us even before we arrived. “Let’s get ready, these people are already crossing,” was what we all interpreted seeing them from the water. They caught us in the river and fixed their eyes on us. But they never made the slightest gesture to give us away, we realized that. They were just waiting for us to arrive. “If you arrive, I receive you, if the river takes you away, fine, but I’m not here to give you away, that’s not my job.” That’s how we understood the message they were sending us.

Central American migratory route: testimony of a Cuban migrant (I)

When we made landfall, they began to approach us. “Come on, come on, put on dry clothes because Immigration is coming to pick you up.” We changed right there, we saw bundles of clothes, shoes, backpacks that had been left by those who had passed through there before. We changed, we put the documents and cell phone in a bag. That’s when Immigration approached us. “You’re in the United States; we’re from Immigration. And you’re going to be prosecuted. Please turn off your cell phones. You’re dry, we’re leaving.” And they guide you and put you in a van. No handcuffs, no shackles. During that time, I managed to take a photo and record an audio to notify my family, both in the United States and in Cuba, that I had arrived in the United States, that I was safe and had not drowned in the river.

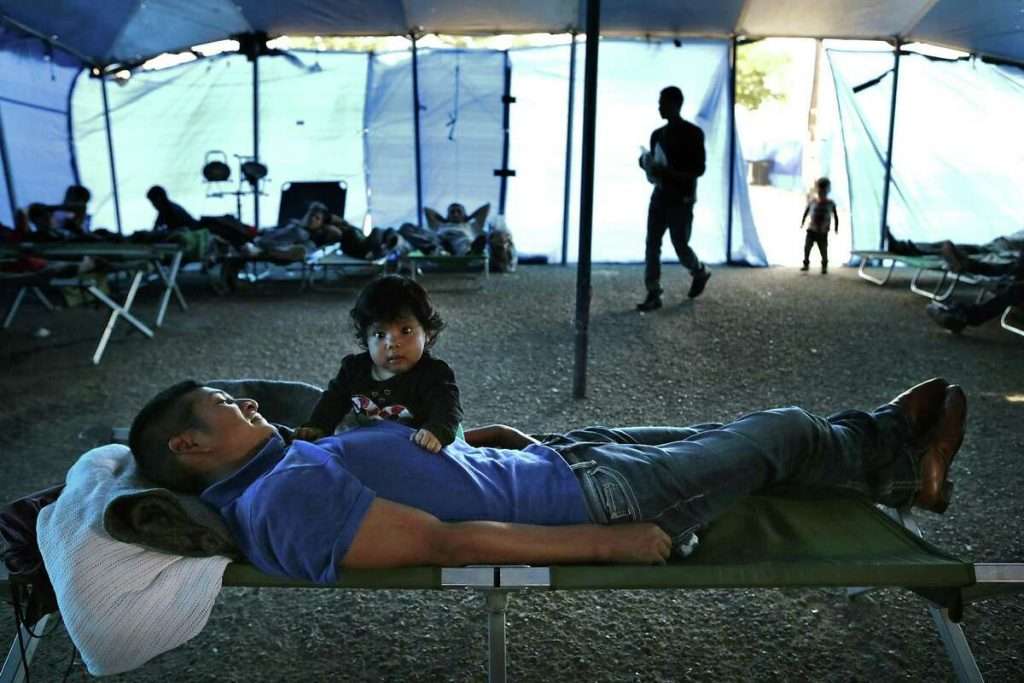

In the Eagle Pass tents

The officer who greeted us was a Mexican. I started crying with joy and he told me: “Don’t worry, you’re here, you’re Cuban, don’t worry, nothing’s going to happen to you. They will accept you in this country. I know that you are here because of Biden, but please, when you’re in there, vote for Trump.” That caught my attention because the last thing we wanted at that moment was to talk politics.

They gave us a bag and told us to put everything we were carrying in there, they took our hair bands, shoelaces, earrings, clothes, everything. And they told us: “you’re going to a detention center where you will be processed.” We reached that place in a few minutes.

The center was not a building but tents. Some very big, huge premises in Eagle Pass, Texas. Upon arrival we were searched. They ordered me to raise the coat I was wearing to see my arms, and the sweater to see my torso. That’s when I found out I had bruises. They immediately showed great interest in knowing if I was a victim, if I had been mistreated, beaten or raped. I told the truth: no, they were bruises I had gotten on the road.

Then they gave us a form: name of father and mother, country of birth, address, if you have an address in the United States, where are you going, telephone number of the person who is going to take care of you in the United States…. They begin to take you away everything you have in the bag and to throw away the things that are not necessary. I had my passport hidden because I thought that I could lose it, and someone had suggested that I turn myself in with my ID card. I then sewed it between two facemasks. That’s how I got it through.

From there they take you to a huge room, where the wait begins for them to call you. A long wait, but a peaceful feeling invades you: “I’m here.” But it is not for an interview but only to register you in the system. They take photos and fingerprints, then they take you to another room and you have to wait for your name to be called. When they call you, they put a bracelet on your wrist with the information of the place where you entered and with your name. From there they take you to another room, where you have to wait for them to tell you where you’re going.

There they divided our group. They put the men on one side, the mother with the girl on another, and the women on another. They are like cubicles.

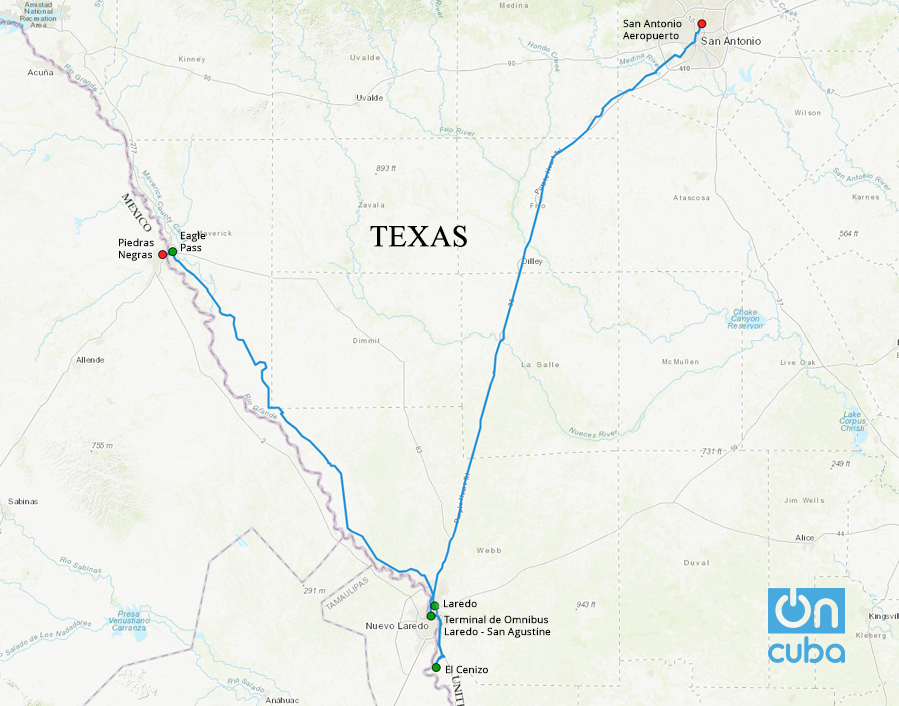

Laredo

Then they transferred us to Laredo. Quite a short trip. In the Eagle Pass tent there was a little more freedom, you could move, you could go out…not so in Laredo. It was a feeling like being imprisoned, detained. We were there for four days and in those four days we ran into all kinds of officials. The one who only spoke English and told you that he didn’t speak Spanish, but deep down you knew that he understood you.

At a certain moment, due to something I did without realizing it, but nothing out of this world, one of them told me: “ma’am, this is not your house, you are under arrest, you are a criminal.” I kept quiet because I was afraid that the process would affect me and they wouldn’t give me the papers. But the next day we ran into officials of Mexican origin. And it was the opposite. They gave us food and even differentiated attention to a pregnant woman, and they even let us watch movies on TV.

But we were all treated the same, regardless of our nationalities. The only difference was when asking what was going to happen to you because you spend hours and hours not knowing. And in there people speculate and speak without knowing. So when you went to look for information with them, the official always asked you: “where are you from? Cuban? Don’t worry, don’t worry, Cubans are not deported, Cubans enter this country easily.” It was the only difference. To those who answered: “I’m Venezuelan, Colombian, Brazilian…” they were told: “well, you have to wait, they are going to interview you, it is going to be difficult,” etc. But the ones that had the worst were the Mexicans. They were deported in bulk.

In there the only colors you see are white and gray. You don’t know when it’s night and when it’s day. There were people from El Paso, Mexicali, Piedras Negras.… Mexicans, Colombians, Venezuelans, Brazilians.… A Mexican woman was traumatized because she had been kidnapped, but not even because of that did they allow her to enter the country because before they gave us the answer of whether ee were going to enter or not, they gave her the deportation order. And they did that with all the Mexicans.

We thought that they were going to interview us because of the credible fear, but that was not the case. They called us by groups of 15, 20 people. They accommodated us in some telephone booths, they asked me the same thing that was already on the form. And that’s it. I tried to talk about my credible fear, but the officer told me: “no, no, no, no, you have to tell the judge that when it’s your court date.”

They gave me the date: December 12, 2023. I got nervous because it was a long time. I started to cry, many things went through my head and they gave me medical assistance. Very different from the tent. There were hardly any medines, too many people inside. They told me to drink water and put ice packs on my forehead.

Well, the day after that interview they called me. I was put in a group with over 40 people. That’s when they told us how we were going to get out of the Laredo detention center. They had given me an I-220 A form, but they never explained to me what the hell it was. That’s when they did explain: “You’re signing a document that says the United States government allows you to stay in the country until your court date arrives and you can show a judge your credible fear. He is going to determine what to do with you, whether you stay or get deported. Meanwhile, the government is going to give you a phone to keep you under its radar.”

And so it was: once a week I have to send them a photo with my location so that they know that I am where I promised I would be. I only have clearance to move within 70 miles of where I’m staying here in Florida.

From El Cenizo to San Antonio International Airport

Returning to Laredo, they then give you all your personal items and put you on a bus after telling you that they are going to take you to a church or to an institution for helping migrants. In my case, I went to a church in a place called El Cenizo. There they told me that there were 35 such institutions in the town. But it’s not entirely free, you have to pay for certain things.

After spending time with them, that depends on your conditions and family support, they move you to the town terminal to take a bus and get to the airport so you can land at your destination. But, again, you have to pay for that trip, the same way you have to pay for the plane ticket, which was covered, naturally, by my relatives in this country.

In short, they left me at that terminal in Laredo to take a bus to the one in San Antonio, Texas. About a three-hour trip. Once in the terminal, you have to manage by yourself how to get to the airport to get on the plane.

I walked out of the detention center in a daze. All I wanted was to reach my destination and be once and for all with my family. When I left the terminal I started seeing the buildings, the skyscrapers. I started seeing the United States. “I’m in the United States,” I told myself as if it wasn’t true. I left Cuba with the idea that I was going to enjoy the things of this country, that I was going to have everything that I didn’t have in Cuba, that I was going to be dazzled. And it was not so.

When I got off at the airport, the first thing that struck me was the air on my face. I had never enjoyed it so much. I don’t know if it was because I spent five days in detention, not knowing when it was day or night. And along with that air on my face, a feeling of freedom, I don’t know if it was because of that or because of how suffocated I felt in Cuba. Walking freely, without any fear, was a wonderful feeling.

I had the electronic ticket for the next day, but I preferred to leave earlier, sleep at the airport and not stay in that hostel; nor did I want to run the risk of missing the flight in the event of a setback on the stretch from Laredo to San Antonio.

The airport closes the cafes and restaurants at a certain time, but the police there have a place where they give snacks to migrants, there are so many of them. I wanted to print the electronic ticket and I approached an airport official. Apart from printing it, he put a sticker on my cell phone that said in English: “I don’t speak English, please help me find the door.” They give it to you because many people have to make connecting flights at different airports to reach their destinations and they don’t even know the language.

I didn’t have that problem because I speak it a bit. I made a stopover in Houston and got on the other plane that took me to my destination. I had never seen such a large airport, nor such a large traffic of planes. That caught my attention.

And here I am, I had practically just gotten here. And with a world of things ahead.