Last week, the president of BioCubaFarma and other senior officials from the sector attended the Mesa Redonda TV program to report on the situation of medicine production in Cuba. Doctor of Science Eduardo Martínez Díaz, president of the aforementioned business group, explained that BioCubaFarma develops 996 products, including medicines, vaccines, diagnostic tools, and medical devices. Of these, 757 are for the public health system, including 60% (369) of the 627 medicines and vaccines in the basic list, 10 more than the previous year.

The official stated that during 2021 “50% of the financial and material resources were used in the production of protocol medicines for COVID-19, as well as for the development of Cuban vaccines —which successfully managed to control the disease on the island. Consequently, “we were not able to have the resources to produce the full range of medicines in order to guarantee the basic list.” This situation “has continued and has worsened in 2022,” he said, while stating that 94% of medicine shortages have occurred because the country does not have the raw materials and materials necessary to produce them.

The medicine crisis in Cuba, as well as the appearances of the officials of BioCubaFarma and the Ministry of Public Health on the evening program of Cuban television to explain it, are far from being something new. This was confirmed by the fact that on June 7, 2019, Dr. Emilio Delgado Iznaga, then director of Medicines and Medical Technologies of MINSAP, attended the Mesa Redonda, where he explained that in 2016 some 100 shortages of medicines were reported due to financial problems, while in 2017 and 2018 there was a trend towards “gradual decrease” in shortages and low medicine coverage. This meant that in 2018 “the least amount in recent years” was reported, with only 38 medicines missing. On that occasion, the M.Sc. Rita María García Almaguer, director of Operations and Technologies of BioCubaFarma, pointed out that at the end of April 2019, “85 shortages were reported, including 16 controlled card medicines.”

A year later, on July 3, 2020, current Cuban Minister of Public Health Dr. José Ángel Portal Miranda and the president of BioCubaFarma appeared to “update on the situation of medicines in the country.” On that occasion, Portal Miranda explained that “at the end of June” “116 medicines were missing (16% of the Basic Table of Medications)” were reported. The situation two years later is even worse. According to an EFE report, dated in Havana on July 19, Tania Urquiza Rodríguez, vice president of BioCubaFarma, explained that the business group “has had an average monthly deficit of 142 products.” Note that this refers only to the medicines that her group produces, so the shortages are surely greater.

During these years, the fundamental causes that cause the shortage of medicines on the island have been maintained. In the first place, “not having the necessary and timely financing to buy them,” as well as problems for the payment to the suppliers due to the refusal of banks to work with Cuba,” according to the officials. All this coupled with the non-compliance of regular suppliers “who stop supplying due to actions related to the blockade.” To the above reasons are added on this occasion: “world deficit of some raw materials and materials for pharmaceutical use, which has worsened in the period of the pandemic” and “effects on international logistics due to COVID-19.” These realities, according to the president of the business group, are aggravated by the fact that the U.S. government has Cuba included in the list of countries that sponsor terrorism.

The impact of this crisis on the life of the country has been enormous; especially because the Cuban population, markedly aging, requires increasing levels of medicines and health services. To give an idea, the demand for blood pressure medicines such as Enalapril went from 151 million tablets in 2010 to 400 million in 2019; Amlodipine (10 mg), increased from 15 million to 87 million; Metformin 500 mg, a medication used in diabetes, went from 42 million tablets to 152 million in the same period, as an expression of two of the most frequent health problems of the population. Another very popular medication, Dipirona 300 mg, also doubled its demand, in this case from 450 million in 2010 to 1 billion tablets in 2018, without the industry being able to meet the demand.

This became especially sensitive in the summer of 2021, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the population’s medicine needs became critical. With the intention of alleviating the situation, after the social protests of July 11 the government authorized “exceptionally and temporarily” the import of food, toiletries and medicines, “without limit of import value and free of payment of tariffs,” until December 31 of that year, a measure that has been extended twice. I remember that in those months the prices of a cycle of Rocephin and Azithromycin, two antibiotics with an auxiliary use in COVID-19, reached exorbitant prices on the island’s black market.

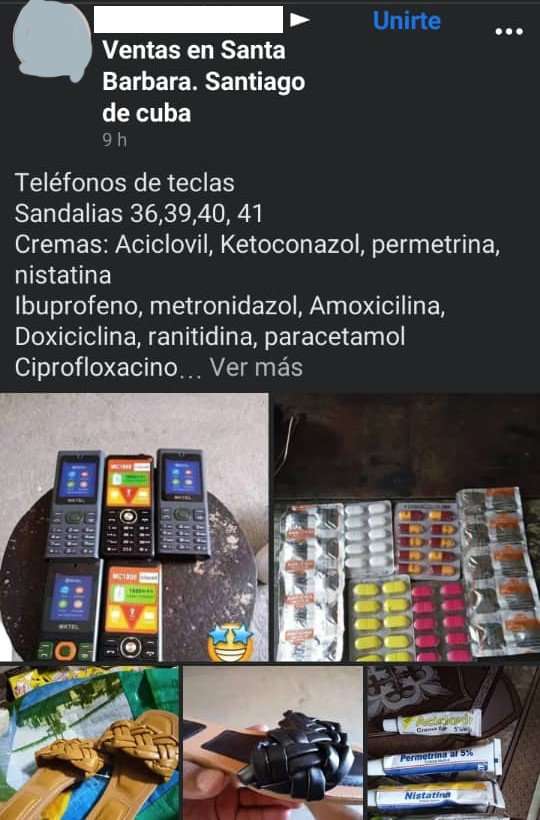

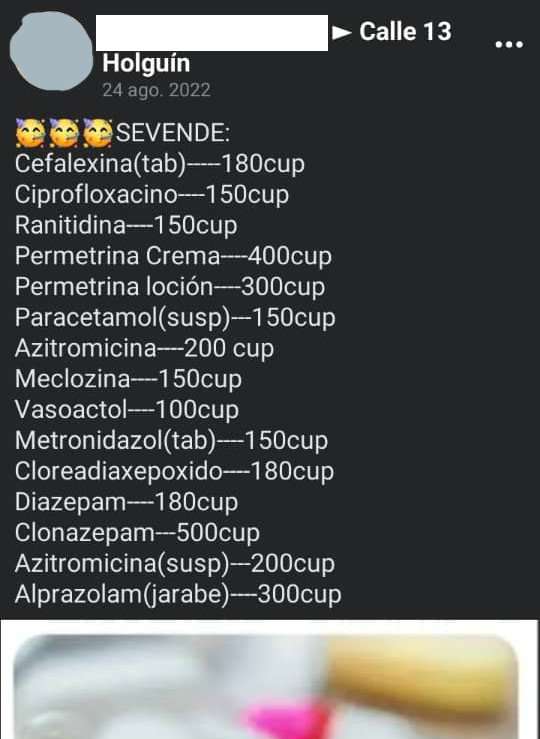

Although the import of pharmaceuticals is explicitly “non-commercial,” these products are sold freely on the informal market. The mechanism is very simple: just enter some of the sales groups that exist on Facebook, look for an offer, request a price list or a specific medicine. The service sometimes includes home sales. In some cases, these are people who are “specialized,” while others market an assortment of products that may also include shoes, cell phones, facemasks, condiments…

In this market, the offer may exceed that of many state pharmacies in terms of diversity of products, which judging by the catalogs include: antibiotics, anxiolytics, vitamins, antacids, analgesics, antihistamines, vitamins, and blood pressure drugs. However, the issue is the prices: a blister with ten Loratadine tablets, a popular antihistamine — widely used by people with allergies, which also has practically no adverse effects —, is worth 170 pesos. Ten Sulfraprim tablets, a very useful antibiotic in urinary tract infections, cost 220 pesos; a complete treatment would reach a value of 880 pesos. Keep in mind that this happens in a context where the pension of an average retiree ranges between 1,528 and 1,733 pesos and can exceptionally reach 2,000 pesos. In these circumstances, the family has to purchase the medicines.

An additional risk is in the commercialization of low-quality, adulterated or expired medicines. Those who are in this business are not people with deep knowledge on the matter, nor is there any type of regulation regarding them. Hence, intoxications and other medical complications can occur from the consumption of medicines without the required supervision.

According to the officials of BioCubaFarma in the aforementioned Mesa Redonda, “there is an import substitution program until 2030 that includes medicines, raw materials…” Along the same lines, Luis Armando Alarcón Camejo, general director of Medsol, a company that produces 35% of the basic table of national production and 77.8% of controlled medicines, specified at the Mesa Redonda that they are working with “nationally produced corn starch thanks to the import substitution program.”

It seems chimerical that the country’s financial situation will improve significantly in the coming months or that the U.S. government removes Cuba from the list of countries that sponsor terrorism, therefore the problems with suppliers and the actions related to the blockade will continue. Solutions will require new ideas and new strategies, otherwise, it is likely that shortages and low coverage will continue, and it is possible that next year the officials of the national pharmaceutical industry will be called to a new Mesa Redonda for “an update on the medicine situation in the country.”