Racism is not a ghost that travels the world, but an invisible factory of stereotypes, exclusions and deep wounds on a good portion of Humanity. It is not simple aversion, but a social machinery that thinks, submits and punishes in subtle or violent ways, depending on the case. It cuts across philosophies and cultures throughout the universe. And in Cuba it was hidden, as years ago it was done with handicapped children, political deserters and unfaithful women; none of them appeared in the family photo. Racism is a very familiar conflict in our society.

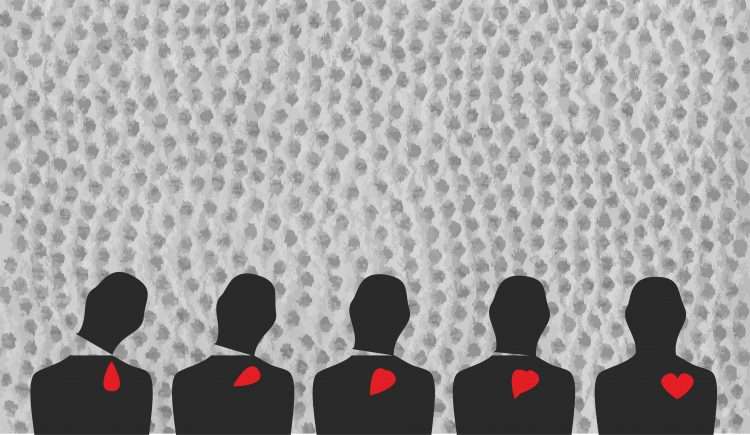

In the last thirty years, anti-racist criticism produced in Cuba has been accused of reproducing visions of other countries and cultures — read the United States or Brazil — and the most critical anti-racist activists are treated as radicals, dissidents or ungrateful; a triad that reduces the conflict to an overly simple analysis, more interested in diverting attention from the presence of a racism that emerged in the only socialist country in the Caribbean. I call this neo-racism, a series of exclusionary and humiliating actions normalized in our daily lives and assumed, even, by many black people.

It is curious how difficult it is to identify racism in Cuba; contrary to the sagacity with which we see any racist event in the world. Thus, we hide our aversion to talking about it here and compare ourselves to those places where black people are regularly imprisoned and killed — like Brazil or the United States. There is also racism in Spain, the Dominican Republic or Germany, but each racism is different, although equally painful. That is why in many countries it is denounced, discussed and laws and policies are designed, difficult to apply, but valuable achievements and tools of struggle: they are the recognition of a conflict, the level of discussion and consensus about it, plus the socialization of explanations and solutions that are lacking among us.

In Cuba, the debate on racism continues to be hijacked between halls, declarations and commissions that avoid any socialization of the subject. It is not the only black hole about which, intermittently, superficially and opportunistically, is usually talked about a couple of times a year in some media space. The lack of a racial policy expresses slowness, incoherence and insensitivity to a problem that has not achieved legal consistency in any court, nor is it recognized as a cultural or institutional practice. Talking about racism has been banned for so long that it is still considered a very sensitive issue.

The racist performance of Holguin’s Halloween was highly criticized, without offering the local context, marked by a high population of Hispanic origin. There is a Cuban racist past with illegally segregated public spaces such as various provincial parks: if someone broke that rule they could even be shot, as happened to many in Santa Clara’s Parque Vidal in 1924, or be assassinated, as happened to the young Justo Proveyer in Trinidad’s Parque Céspedes in 1935,1 among other events that took place in Cienfuegos or Camagüey, where, incidentally, in 1929 a sect named The Invisible Imperial Palace of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan was announced.2

The young people from Holguin who asked “Where are the blacks?” probably don’t know how the black soldiers of Fort Pillow were massacred, by order of a General of the Confederate troops, also a slave trader, named Nathan Bedford Forrest, who in 1886, in Pulaski, Tennessee, founded the Ku Klux Klan, a terrorist organization which later spread throughout the southern United States as a secret brotherhood of white men who hated blacks, illegally expropriated their property, raped their women, and terrorized their communities with two favorite rituals: hanging black people and burning their homes, schools and churches. They also assassinated some white politicians, allies of the blacks.

In the 20th century, starting in 1915, they attacked Jews and Catholics. In the 21st century, the so-called “Klan” recovers the Confederate flag, recruits hundreds of members and on its Internet platform stands as “a national-based movement, made up of white Christian men, women and children who support a return to government by white Christians.” In the same website they have campaigned against the return of the boy Elian, for the closure of U.S. borders and to eliminate laws against the possession of weapons. The KKK is a living force in the United States, linked to racism, xenophobia and white supremacy that Donald Trump exacerbated, also against white Cubans who, in the United States — although not in Miami — stop being white to become Hispanic or Latinos, by not classifying as WASPs, the founding ethnocentric code of that nation of immigrants.

This is, broadly speaking, the context that seems foreign to the young people of Holguín. I think they are guilty with extenuating circumstances, because they are the result of ignorance, that is, of their education. They are strange fruits of the Cuban neoliberal harvest of the 21st century. His Halloween walk became a boomerang for the ambitions of a middle class with economic power, culturally deceitful and inclined to the American dream in its vernacular variant. Beyond inserting Halloween among the few Cuban holidays, there is an economic, political and cultural model that, since the end of the last century, accommodates its exclusive values and reproduces them in the face of the shortcomings of the old verticalized model of the nation, little given to critically socializing inside and outside values. Both models coincide in their dependence on the Yankee commercial framework, despite the blockade and its remakes. (The cultural and self-critical analysis of the blockade is pending).

Behind this absurd youthful provocation, but equally racist, hides the paternalism and secrecy with which the racial issue continues to be treated in Cuba. In addition to the sugary idealism of certain television spots that persist in idealizing that narrow, outdated and unscientific idea of Cuban color; valid in the thought of Nicolás Guillen in the 1930s, when he launched very successful ideas and others not so much, such as his thesis on the celebration of racial miscegenation, mulattoism and the Cuban color itself; today assumed as a romantic anti-racist campaign.

The current Cuban racism is also renewed under other actors and spaces that do not name it but use and control it as they please. It is a covert racism, sophisticated when it comes to gentrifying our cities or making certain neighborhoods and communities more precarious. Imposing new norms, tariffs and imaginaries, to which high bureaucrats, new entrepreneurs and nightclub doormen quickly adapt, regardless of their public or private status and the color of their skin.

The growing implosion of racist events in the country incorporates all the signs of the current political crisis. And vice versa: each of the signs of the crisis — although some do not take up the racial question — make visible the many variables that affect the black population and mark their absence in key debates and sectors. On the other hand, the already exhausted, fragmented and co-opted Cuban anti-racist activism has a hard time raising its voices beyond the issues of black entrepreneurship and aesthetics, its academic niches and new self-promotional projects and actions, with black middle-class aspirations. without much racial awareness or other capital required for it.

They are legitimate aspirations, but they lack the critical edge with which anti-racism was born in the 1990s in the midst of debates open to the public; with denunciations, catharsis and the recognition of a publicly aired social malaise. In less than a decade it became an anti-racist movement, with various tendencies, which ended up creating a political space, if not its own, very unique. That activism was dismantled by a strategy of power that eroded the anti-racist discourse to the point of seeing it surrendered by the promises, fears and uncertainties of the moment. The silencing or abandonment of critical discourse opened the way to a racist language that, in turn, reactivates the classist language that emerged in many post-J11 discourses, not only when talking about black men and women, but also when referring to poor people, marginalized and protesters.

That activism died, whose greatest inability was not to turn anti-racism into a cultural practice, in part of the civility that we need to explain other conflicts. It was difficult to assume a culture of public responsibility and vigilance, as feminisms have achieved in Cuba, in spite of everything. Today this possibility is more distant than 15 years ago when Cuban anti-racism emerged as a criticism of the coloniality of domestic politics, that coloniality that configures socialist domination that I explain in a 2015 text, where I warn that: “The coloniality of power has three great accomplices in Cuba: neoconservatism, internal colonialism and neo-racism, about which there is not enough public questioning.”3

Understand that racism and anti-racism are simply permanent experiences in our private and public lives. Not isolated or exceptional events, as the culturalist view usually sees it; but every day and profound, structural and transcendent. Only racial prejudice, political cowardice and ignorance will evade the mechanisms of that vile social machinery that is racism, beyond those who reject or reproduce it.

If the civic forces of a society cannot express their discomfort and aspirations, participating and debating ideas or proposals, they will find their own ways of defending and celebrating the nation, their own spaces for political criticism and resistance. This is how a new anti-racism emerges that blindly denies the previous one, although it feeds on its small achievements and learnings. The forecasts are not reassuring. Some rumberos from the neighborhood answered my question “Where are the blacks?” with ingenious street responses: “We are not invisible. You know where we are. I don’t have a passport.” They don’t know about strange fruits or cheap lemons. They live a reality without masks. Lacking. Hot.…

In Cayo Hueso, Havana, November, 2022.

Roberto Zurbano. Cultural critic and anti-racist activist.

***

Notes:

1 Zurbano, Roberto: Cruzando el parque ¿Hacia una política racial en Cuba? in Humania del Sur. Journal of Latin American, African and Asian studies of the Univ. of Los Andes, Venezuela, no. 31 (Jul.-Dec., 2021), p. 137-170.

2 Henry Night, Kezia Sabrina: “La revista Minerva. Una voz contra el Ku Klux Klan en Camaguey,” in the Bulletin of the Office of the Historian of the City of Camagüey in www.ohcamaguey. Accessed November 1, 2022.

3 Zurbano, Roberto: “Racismo vs. Socialismo en Cuba: un conflicto fuera de lugar” (notes on/against internal colonialism) in Revista Meridional (Chile), April 2015. There is a Cuban edition in Revista Cubana de Ciencias Sociales, número 54, Institute of Philosophy of Cuba, 2021, p . 243.