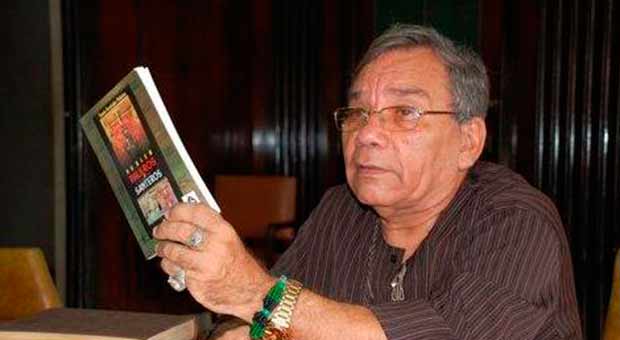

Bob Marley once said: “wars will go on as long as the color of the skin continues to be more important than the eyes”. Such subliminal phrase synthesizes the work and personality of Tomas Fernandez Robaina, Tomasito, a 70-year old man many consider the academician in town and who has been working at the Jose Marti National Library for more than half a century (51 years): “moving rocks and trash away–doing some work– this little happy man is always turning dirt in gold”.

He is the author of a considerable number of books on the social history of black people in Cuba and has also tackled different topics on popular religiousness and already holds three literary testimonies. He is multifaceted as to the topics he writes about and hedaily leaves home in the municipality of Cerro in Havana to make a living.

In an exclusive interview for OnCuba, he agreed to share some of his countless experiences.

What’s your assessment on the current state of the topics you have defended in your books, talks and courses?

There has been a lot of progress, now there are more spaces for discussing subjects that were not mentioned before, particularly on the racial issue in Cuba. One of the achievements is raising awareness on the fact that there are actually racial issues in Cuba in the form of unconscious prejudice and discrimination and that these must be fought back with energy. Another aspect that should be noted is that this struggle against discrimination should not be limited to race, but it should rather expand to current and more visible or hidden ways of discrimination in terms of religion, gender, homophobia, and regional matters. I’m optimist in these regards and with the inclusion of youngsters from all over the country that study and research these topics and call the attention of authorities about what they should fight objectively.

In your opinion, what are the greatest challenges to come?

First of all, understanding that everything we do individually or as part of the Brotherhood of the Blacks, the Regional Articulation of Afro-descendants from Latin America and the Caribbean, the Afro-Cuban group, or UNEAC’s Aponte Commission, among others, is guided by the main purpose of fighting racism and its effects. Secondly, assessing objectively the viewpoints of different individuals and groups that are against racism and all sorts of discrimination and prejudices. Achieving consensus in what brings us together with the purpose of safekeeping the progress we have had so far withthe triumph of the Revolution. And there is another important challenge: believing that spreading analytical and critical knowledge on our historic and contemporary reality among the neediest for that knowledge so that they can join our struggle actively means unleashing chaos and danger. We cannot retake the idea that talking about these issues means creating chaos. Community actions are necessary for supporting racial measures and policies our government will adopt taking into account the advanced level debateshave reached in view of such issues.

On what are you working on today both, as to researches and social activism?

As to research, I’m preparing a course and its book on periodical publications of black Cuban societies; modestly I’d like to pay homage to Carlos Manuel Trelles, Pedro Deschamps Chapeaux, Carmen Montejo and Oilda Hevia Lanier, among others, who contributed with paradigmatic works in this part of our historiography or our hemerography. I will continue my work as activist, which is very linked to teaching; I make the most of every space where I have the opportunity to talk about our fight in order to raise awareness on the need of taking part in that fight with love, hoping that the next generations won’t have to deal with such obstacles. That’s why, it is so important to take the first steps so as to eliminate prejudices from the root, which are hidden to prevent them from being abolished.

For many years you have had important exchanges in universities and institutions in the United States. What’s your appraisal on these experiences?

These have been important experiences for me and they have made me fell more Cuban and identify myself more deeply with our culture and our history. We give seminars, talks on our history and our present and our achievements and deficiencies objectively, honestly, making emphasis on awareness and decisions taken to overcome them, which nowadays are more visible. These have been a great opportunity.

To what extent do you consider they have contributed with your professional and personal development?

Part of what I said earlier answers your question. However, I have to insist in that these experiences in the US where some sort of political training. I haven’t been to big tourist centers everyone longs to visit.They took me to see every contradiction in the US lifestyle; they took me to talk with Haitian, Dominican, Puerto Rican and other communitiesof people from Latin America, Europe and Africa. This allowed me to perceive positive and negative aspects of the US society. As I listened to them, I recalled the words by my professor Walterio Carbonell, as to dialectical presence. I can assure you that I have been able to better understand social processes that are taking place in our continent thanks to that knowledge on the US social reality; let’s not forget that our National Hero was not mistaken when analyzing the essence of the US of his time and what was coming for Latin America as it occurred in the US first imperial war invading Philippines, Puerto Rico and Cuba.

Can you mention some of those universities and institutions that have had a significant role in your life?

My first talk was in the University of Texas, in Austin, in November 1991, is unforgettable as well as my visit to Chicago University, where I returned for a second time for a seminar, as I have done in many others, but those universities, which I visited during the 90’s, as well as Miami’s impressed me the most and impacted me professionally. We must not forget that in the Library of Miami’s University in the Cuban Heritage section not one but the first and most important bibliographical collection on Cuba in the US. My 19 trips to the US have enhanced my knowledge on that nation, they have allowed me to observe the imperial policy they use and the men and women fighting against that imperial power are different things. This is revealed in the support by many sectors of that people of the Cuban revolution with its ups and downs. I’m proud of the fact that my first trips were promoted by colleagues such as Ben Jones, Fannie Rushing, Laurence Glasco, Aline Helg, who absolutely trusted in me and invited me to their events in their universities. There is also the Arturo Schomburg Library, which belongs to the system of Public Libraries, in the city of New York, which I consider my home. Since 1992 I researched its fabulous collections and I collaborated and shared wonderful formative moments because there I expanded my knowledge on the Caribbean by exchanging professional and personal experiences with specialists and technicians that talked to me about their places of origin, their political ideas, always looking to the future, sporadically. Thanks to Howard Dodson, the director of the library, and Miriam Jiménez Romaní, and Diana Lachatañeré, every time I got there it became a classroom where I learned a lot about black people in our hemisphere. Another institution I have to mention is New York’s Buildner Center and its director, Mauricio Font; this is a space where I have debated vehemently and passionately on our current reality. I have something to say about all the universities and institutions I have visited, but that’s the content of a book where I will share my experiences in Mark Twain’s land.

There was a broad debate somehow questioning your work as activist and some others’ a few weeks ago, in an important meeting, on the occasion of the International Day against Racial Discrimination. What do you have to say about it?

That was sad and regrettable; I didn’t say anything I hadn’t said before. I noted I was sorry for the misinterpretation of my words. I didn’t mean to be an agitator by expressing my view that racial debate and debate against all kinds of discrimination should come out from the academic space to the parks and community houses, to the neighborhoods. I don’t believe that goes against the premise that everything should be made from power. I think that open and public debates in the bases of our society are vital. I know that they are creating new programs for the different levels of our educational system, which is an objective means to create conditions for shaping students and teachers more objectively in the short and long term. That shows we are making some progress.

I think we must work more in what brings us together, rather than thinking that differing criteria can be damaging when such criteria are raised by people objectively committed and identified with our struggle as usual. This incident has allowed me to confirm not all the people present there misinterpreted my words because the messages on the internet prove so. Furthermore, my colleagues from the Anthropology course, run byDr. Antonio Martínez, made amends during the class on March 27. I’m of the opinion that as a result from this regrettable event, we are all stronger and more optimist and confident in the struggle we still have to fight.

At present, Tomasito remain an incessant fighter, despite all his years of hard work. Can we assure he will continue his line of work? Or is he bringing in new things?

I always have to go back to me Professor Walterio Carbonell; I don’t know what may come up in our struggle that I should pay attention to and add as fundamental in my struggle for a better work. But there is an undeniable truth: conditions that make us claim from revolutionary stands against all kinds of discrimination, which have survived despite the efforts made by the Revolution to fight them, are powerful reasons to continue our fight, which will stop as the surrounding reality shows a decreaseand until they are completely abolished.