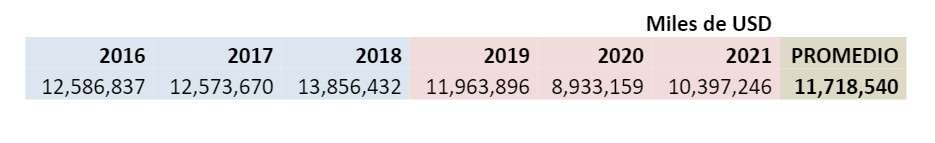

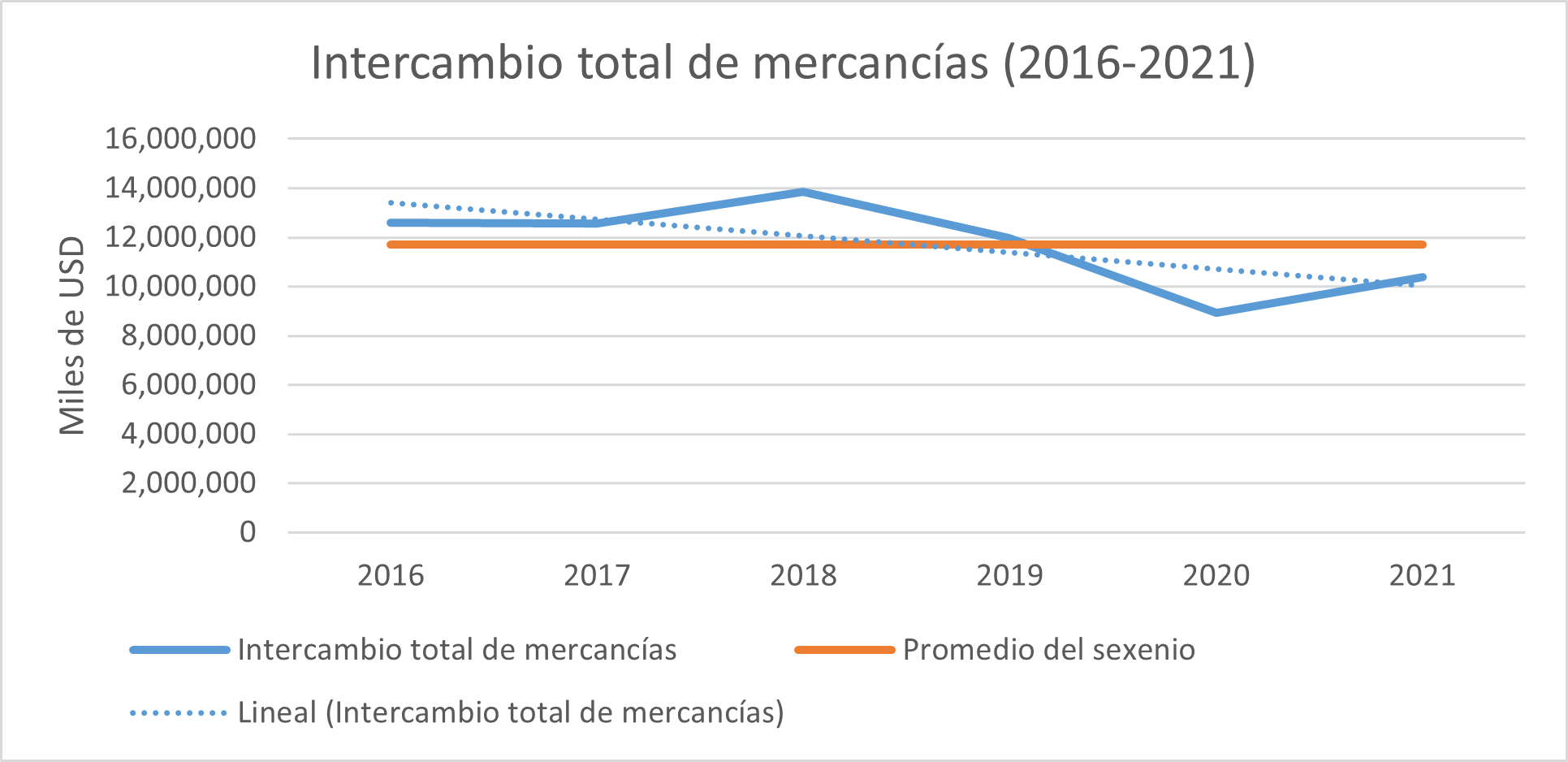

In correspondence with the three main scenarios of Cuban foreign policy towards 2030, outlined in a previous comment, I will consider here some relevant trends in Cuban trade exchange during the six-year period 2016-2021, through my own statistical analysis based on available official figures.1

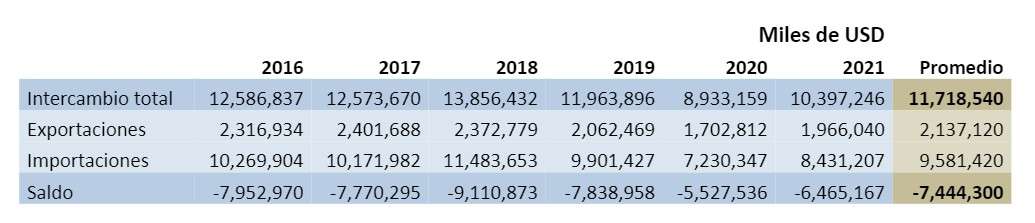

During the second part of this six-year period, there was a notable contraction in the value in U.S. dollars2 of the goods exchanged by Cuba with other countries. Although in 2021 there was a slight rebound, it was not enough to reach the six-year average, much less to come close to the highest record achieved in 2018.

It should be noted that the sharp decline in Cuban foreign trade began in 2019, a pre-pandemic year, and is attributable to the tightening of U.S. sanctions and the accumulated effects of the chronic crisis of the Cuban economic system. Subsequently, the pandemic exacerbated this trend.

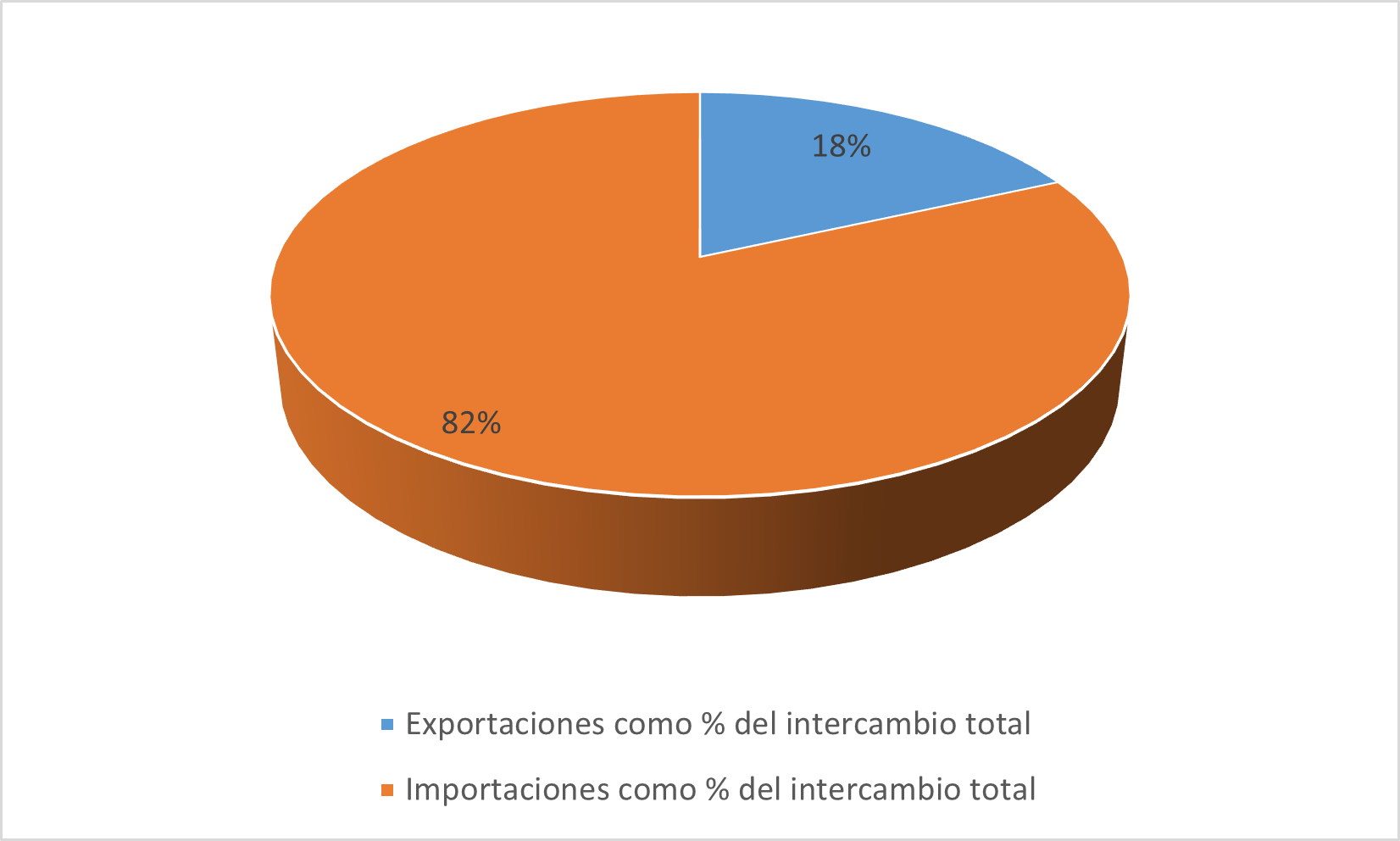

During the six-year term, the long-standing historical trend related to the persistent trade imbalance in favor of the import of goods was maintained, which as an annual average represented 82% of total trade.

In order to evaluate the possible implications of Cuba’s trade in goods from the point of view of international politics, I propose a classification into three groups of the 193 member states of the United Nations, as follows:

United States + European Union (EU) + allies and partners (54)

Albania, Germany, Andorra, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Canada, Czechia, Cyprus, South Korea, Croatia, Denmark, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, United States, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Iceland, Marshall Islands, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, North Macedonia, Malta, Micronesia, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Norway, New Zealand, Netherlands, Palau, Poland, Portugal, United Kingdom, Romania, San Marino, Serbia, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and Ukraine.

China + Russia and their allies (7)

Armenia, Belarus, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan

Non-aligned countries (132)

Afghanistan, Angola, Antigua and Barbuda, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Argentina, Azerbaijan, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados, Bahrain, Belize, Benin, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Brunei, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Bhutan, Cape Verde, Cambodia, Cameroon , Chad, Chile, Colombia, Comoros, Congo, North Korea, Ivory Coast, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, United Arab Emirates, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Fiji, Philippines, Gabon, Gambia , Ghana, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Solomon Islands, Jamaica, Jordan, Kenya, Kiribati, Kuwait, Laos, Lesotho, Lebanon, Liberia , Libya, Madagascar, Malaysia, Malawi, Maldives, Mali, Morocco, Mauritius, Mauritania, Mexico, Mongolia, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nauru, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Qatar, Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Dominican Republic, Rwanda, Samoa, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saint Lucia, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Syria, Somalia, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Sudan, South Sudan, Suriname, Thailand, Tanzania, East Timor, Togo, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, Uganda, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Vietnam, Yemen, Djibouti, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Like any other, this classification could be controversial, but I think it describes quite well the three fundamental factors in contemporary international politics, namely: the U.S.-led bloc, the Sino-Russian partnership, and the non-aligned countries.

The location of some countries in one or the other group could also be debatable. I have followed some basic criteria to minimize any subjectivity. The decisive criteria to identify belonging to the first group have been membership in NATO or in the European Union, or the existence of a highly accentuated relationship of political dependence of the country in question with respect to the United States through binding agreements.

As for the second group, to identify Russia’s allies I have strictly considered the member countries of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which are also members of the Eurasian Economic Union (with the exception of Tajikistan).3

For its part, the third grouping is made up of an amalgam of 132 nations with remarkably diverse and fluctuating political orientations, and which may lean towards one of the first two groups with greater or lesser intensity, depending on the situation and the issue in question. However, they share the condition of not being bound by security treaties or other agreements in political or economic matters that imply an automatic alignment with any of the great powers in the face of major issues of international politics, such as the war in Ukraine.4

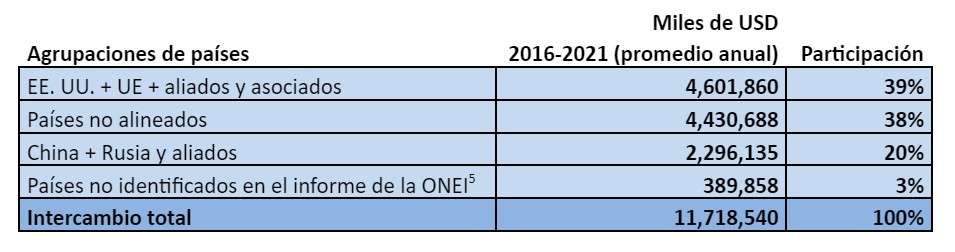

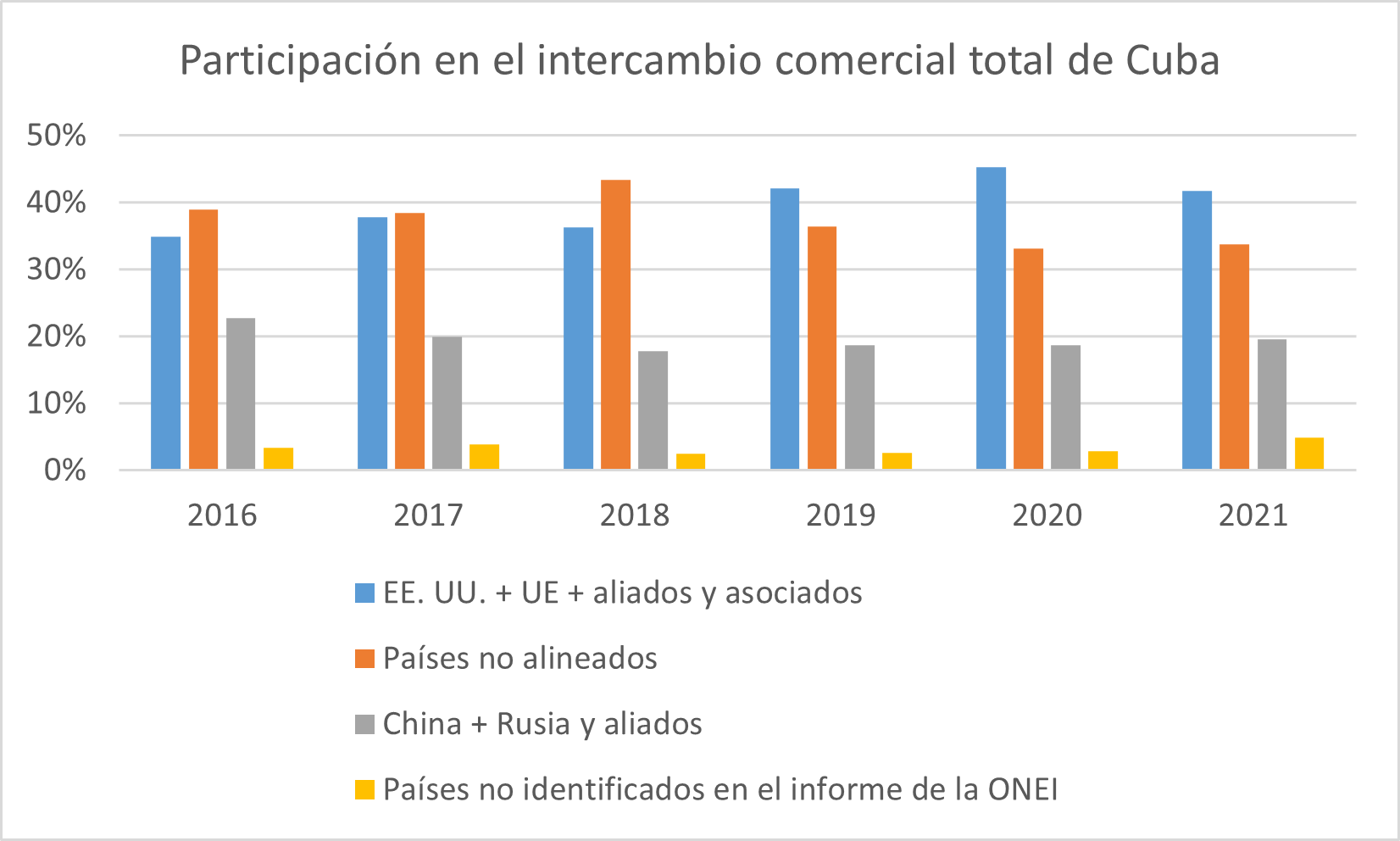

As an annual average in the six-year period analyzed, Cuba’s trade in goods was distributed among these three groups as follows:

The most notable trend was the increase in the participation of the bloc led by the United States, mainly to the detriment of the non-aligned countries, since the participation of the Sino-Russian group remained relatively constant. A decisive factor in this evolution was the marked decrease in trade with Venezuela (which went from 3.103 billion in 2018 to 1.349 billion in 2021).

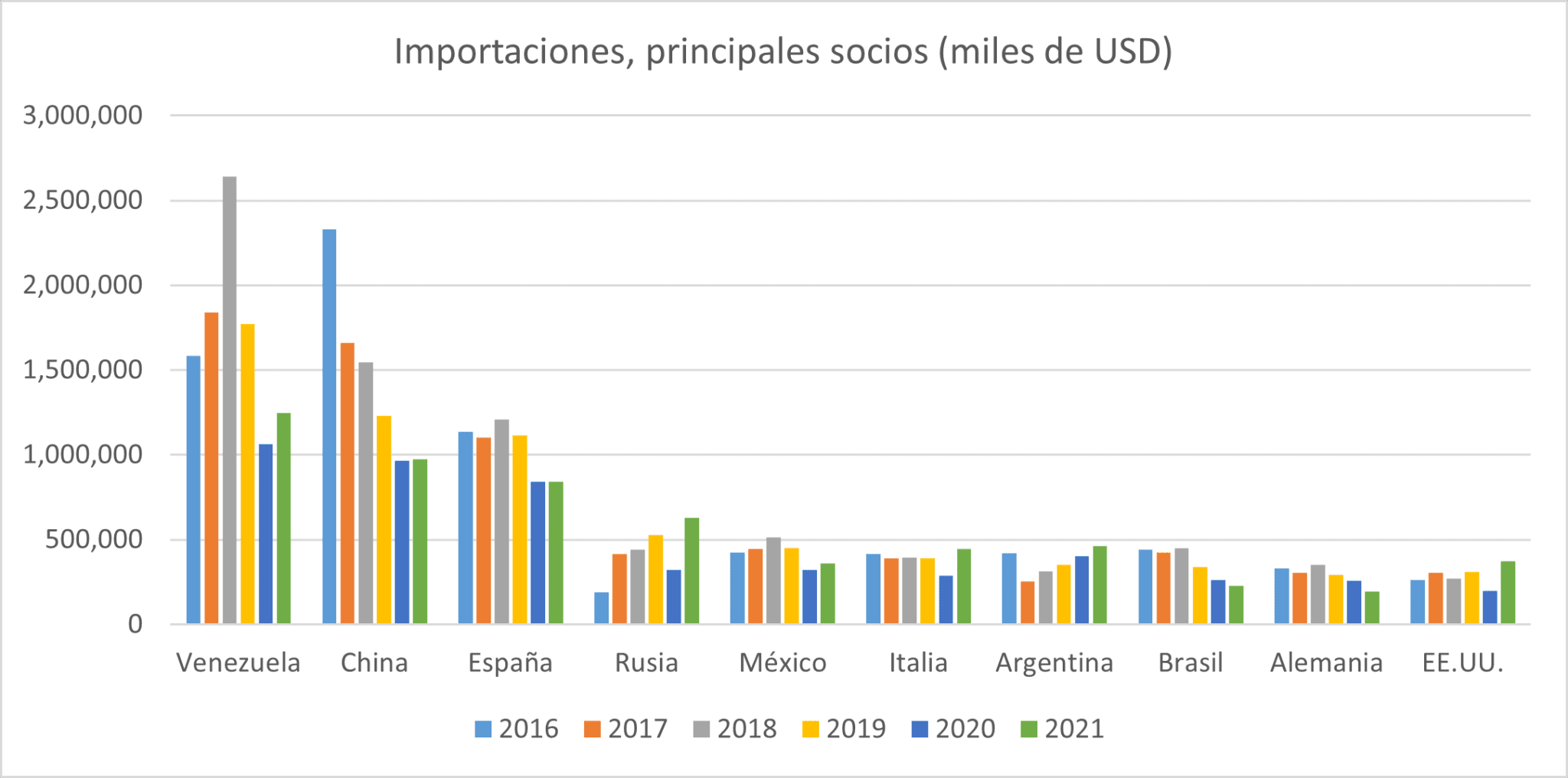

On the import side, Cuba’s ten main trading partners, according to the six-year annual average, are reflected in the following table and graph:

Among the observable trends, the abrupt drop in imports from Venezuela and China stands out. Purchases from Spain also fell, although less sharply. There was also a significant increase in purchases from Russia, which exceeded the figure reached in the period before the pandemic and the start of the war in Ukraine, and made it move to fourth place, although on average for the six-year period imports from that country represented barely 25% of those originating in Venezuela.

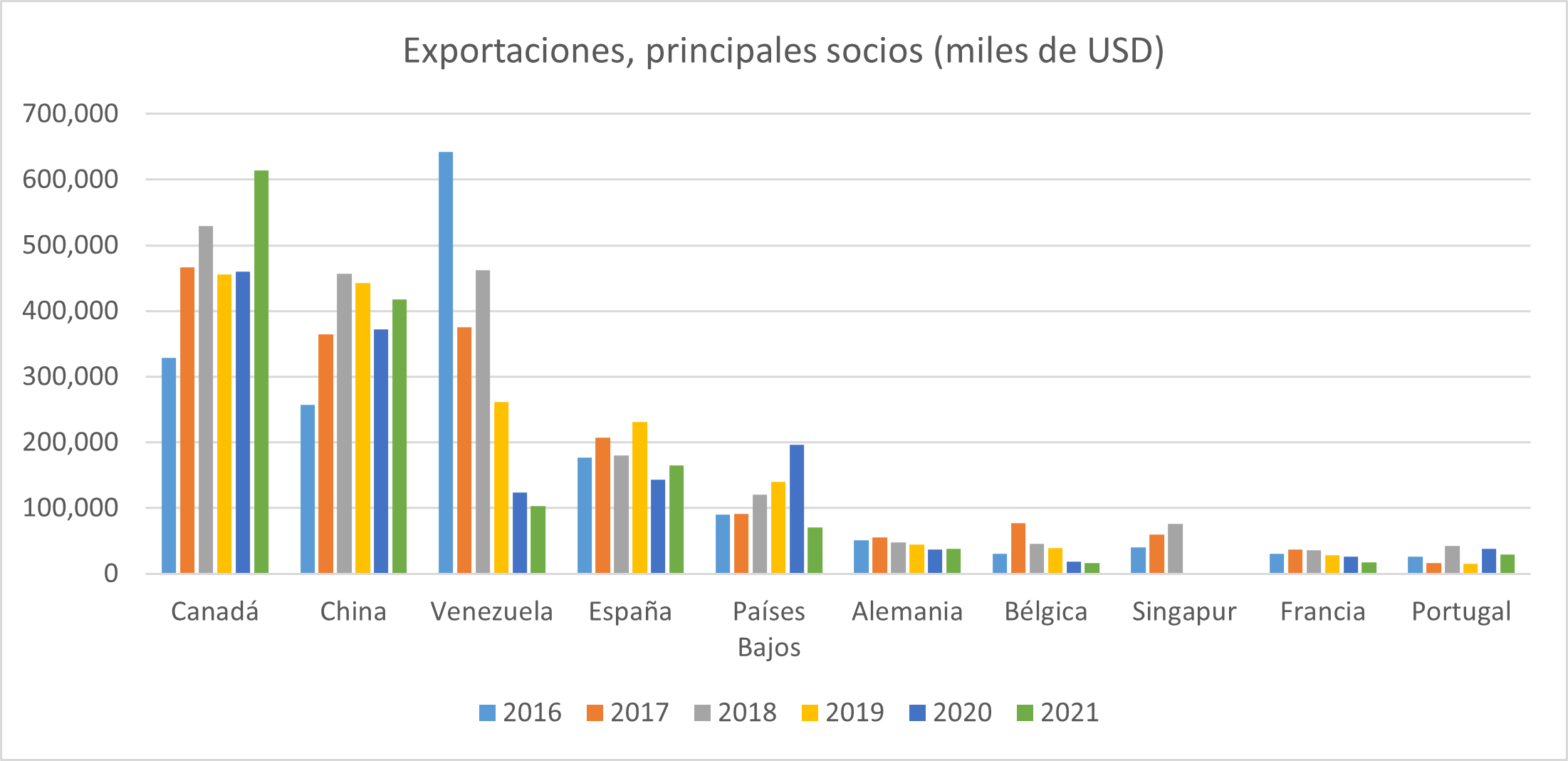

On the export side, Cuba’s ten main trading partners, according to the six-year annual average, are shown below:

As notable trends, it is worth noting the stability of exports to Canada (which reached their highest record in 2021, despite the pandemic situation), the positive trend of exports to China and the abrupt drop in sales to Venezuela.

On the other hand, as part of the historical imbalance in Cuba’s foreign trade in goods, it should be noted that only five trading partners receive exports worth more than 100 million. Likewise, the fact that, unlike what happens with imports, apart from Venezuela, it is striking that no other Latin American and Caribbean countries are among the ten main destinations for Cuban exports.

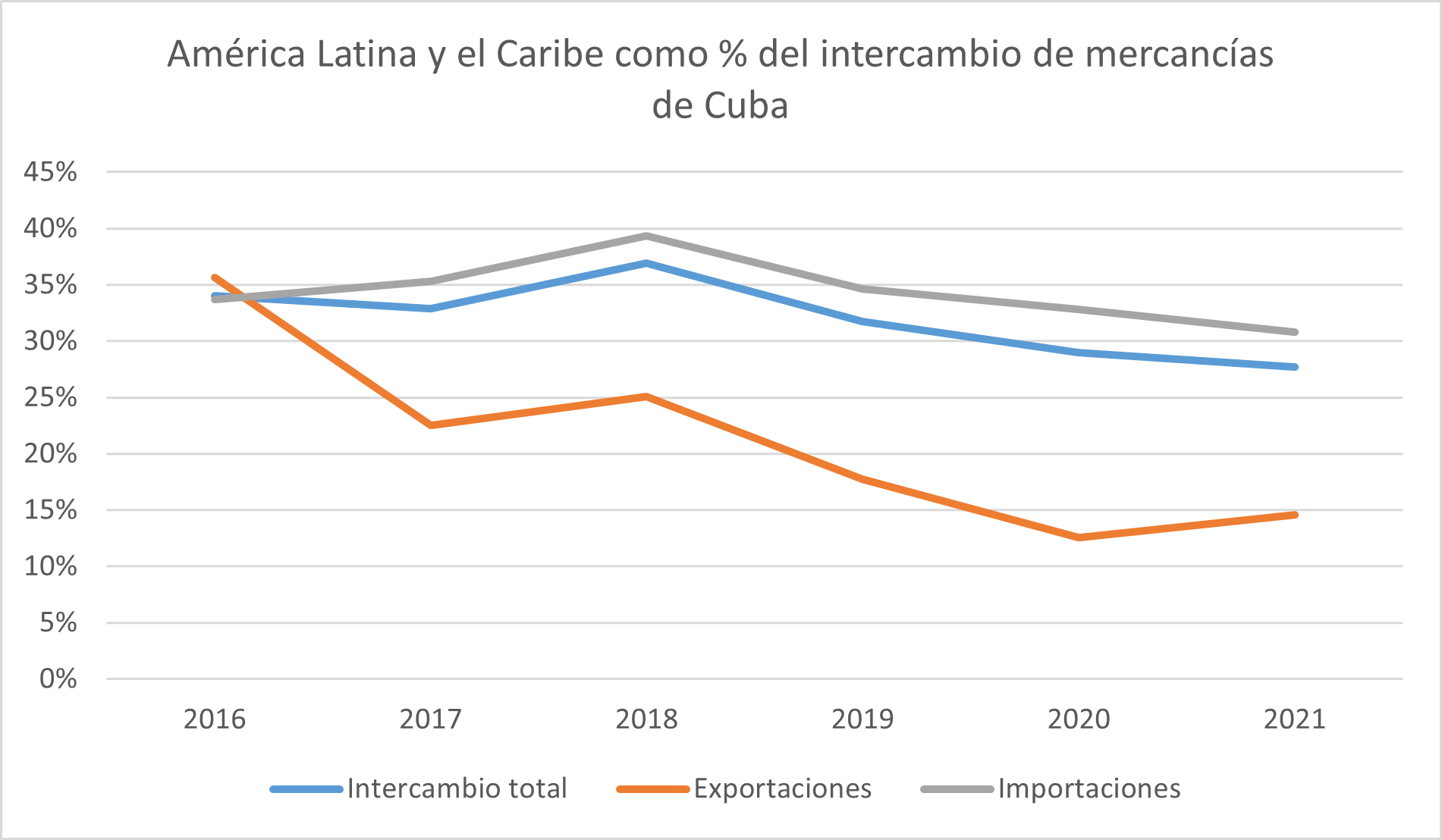

With regard to the integrationist vocation of Cuba with Latin America and the Caribbean, endorsed in the 2019 Constitution, it is convenient to observe the evolution of the region’s participation in its total trade in goods, characterized by a decreasing trend (more pronounced from the side of exports), in which again the contraction of trade with Venezuela is the main explanatory variable.

Based on the data previously presented, it is possible to identify some relevant implications for Cuban foreign policy:

In the first place, the strategic importance of the trade relations with Canada should be highlighted, as the main destination for Cuban exports and the only partner with which Cuba registers a significant trade surplus (more than 200 million as an annual average during the six-year term). This aspect is inextricably linked to the fact that the northern country is one of the main foreign investors in vital productive sectors of the Cuban economy.

The case of Canada, as an important political ally of the United States, shows that in Cuba’s bilateral relations there is no deterministic relationship between political positions and economic deals, as happens with European countries, although this does not deny the very high probability that a better relationship from the political point of view could lead economic relations with these countries to much higher levels.

On the other hand, to the extent that the Cuban government does not seem to have any intention of modifying its fundamental and traditional international policy positions, it must carefully handle the contradiction posed by the increased participation of the group of countries led by the United States in its foreign trade, since this trend, if accentuated, could place Cuba in a situation of extreme strategic vulnerability.

In this sense, any increase in the relative participation of the group of non-aligned countries and of the Sino-Russian association will surely be favored by the Cuban authorities — as it seems to be already happening — in order to maintain a healthy diversification of foreign trade. without this implying a politically motivated decrease in economic relations with the bloc led by the United States, in absolute terms, which would not correspond to Cuba’s traditional foreign policy and would be a luxury that its battered economy can in no way afford.

Likewise, the significant decrease in trade with Venezuela is worrisome, at least until 2021, as it is Cuba’s main political partner throughout this century. Although, from a strategic point of view, it is convenient for Cuba to reduce its excessive dependence on trade ties with Venezuela, the desirable thing would have been to achieve that objective through the relative and diversified increase in economic ties with other countries, and not through the decrease in absolute terms of trade with the South American country.

In addition, as I have pointed out above, the significant decrease in trade with Venezuela determines a more far-reaching negative trend, related to the decrease in the participation of Latin America and the Caribbean, as a region, in Cuba’s trade exchange with the world, with which the integrationist discourse of the Cuban government loses a good part of its real support.

On the other hand, for temporary reasons, the figures reported so far by ONEI cannot offer empirical evidence on a supposed “Russification” of the Cuban economy, although in 2021 there was a significant increase in trade with Russia. We will have to wait for the publication of the figures for 2022 and subsequent years to be able to objectively assess this issue.

A priori, I believe that neither Cuba nor Russia currently have the conditions to resume a bilateral relationship as intense as the one that came to exist with the Soviet Union in the last century, but everything that can be advanced will always be very beneficial for Cuba, in a situation characterized by the scarcity of alternatives in its external economic relations.

Last but not least, during the six-year period under analysis, Cuba’s total exchange with China showed a marked decrease. However, as a very positive aspect, Cuban exports to the Asian giant increased by 62% during the same period, reaching 417 million. And despite the total decrease, China ranked second in both imports and exports, according to the respective annual average values, ousting Venezuela in 2021 by a small margin from first place in Cuba’s exchange with the world, with 1.389 billion.

Compared to Cuba’s $371 million in trade with the United States (made up almost entirely of imports), and for many other reasons, it is clear which way Cuban foreign policy will tend to lean in the face of an increasingly contentious Sino-U.S. relationship.

________________________________________

Notes:

1 The Cuban Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI) has not yet published the data corresponding to 2022.

2 All values referred to in this article are given in U.S. currency.

3 Regarding Cuba’s publicized relationship with the Eurasian Economic Union, it should be noted that, in addition to the important trade with Russia, the ONEI report only records the very modest trade with Belarus (just over 8 million in 2021). In the cases of Armenia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, the existence of bilateral trade is not recorded, although it is not ruled out that some exchange has occurred, included in the overall number of countries classified as “Others” in the report.

4 This grouping that I methodologically propose should not be conceptually identified with the Non-Aligned Movement, although its 120 members are included in it.

5 The fact that the ONEI information reports a certain volume of Cuba’s trade with “other” countries, without specifying them, poses a difficulty from the analytical point of view and determines that we must take this percentage distribution by groups with some reserve from the statistical point of view. If, for example, we assume that this 3% of trade with unidentified countries corresponds entirely to non-aligned countries (an unlikely situation, although not impossible), then that grouping would become the majority in trade with Cuba by a narrow margin, adding 41%, compared to 39% accumulated by the group of countries led by the United States.