U.S. films’ fascination with Cuba and Cuban things is almost as old as cinema itself.

First the island was a landscape, an open lens to shoot diverse scenarios of the Spanish-American War.

Then it was epiphany, music, tourism and romance, perhaps Hollywood’s most used historical perspective, typical of movies like Weekend in Havana (Walter Lang, 1941), with Alice Falle and Carmen Miranda; Guys and Dolls (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1955), with Marlon Brando, Jean Simmons and Frank Sinatra, and Habana by Sidney Pollack, with Robert Redford (1990).

More recently, Chico and Rita (Errando, Trueba and Mariscal, 2010), an animated cartoon whose action takes place in several of the world’s capitals, a sort of peculiar turn of Buena Vista Social Club.

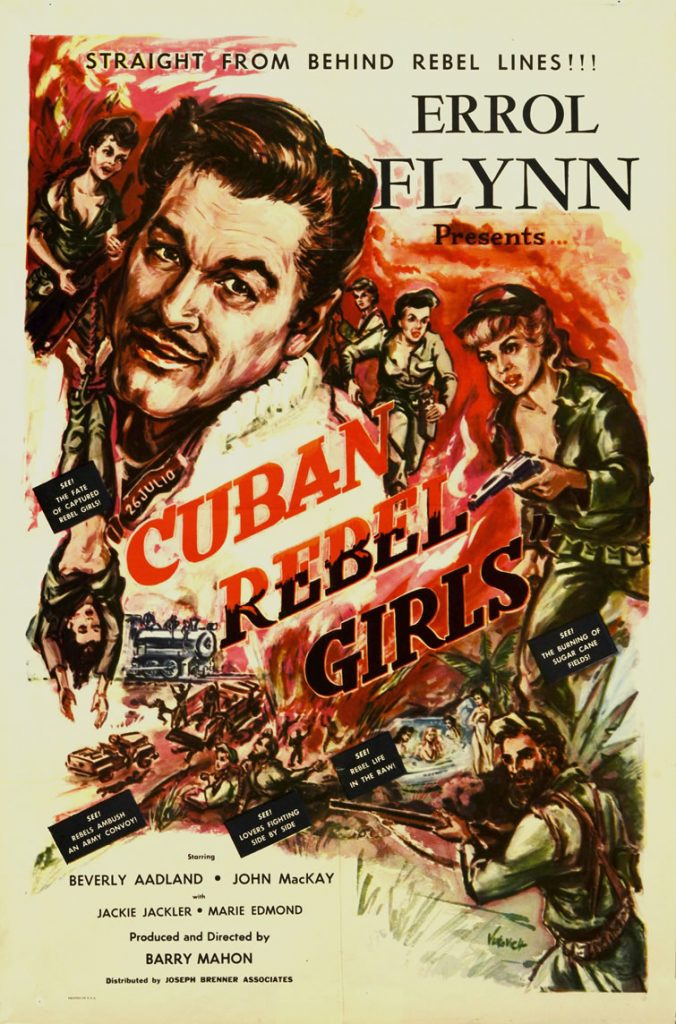

Cuba was also favorable ground to reflect social and revolutionary upheaval, such as We Were Strangers (John Huston, 1949), an anti-Machado drama that logically culminates in what is probably one of the most disastrous attempts at political cinema in the world like: Cuban Rebel Girls (Barry Mahon, 1959), a soap in the very middle of the Sierra Maestra starring an Errol Flynn who’s Robin Hood cape was by then too worn out and his elbow too broken.

But the empire of the pre- and post-revolutionary Cuban mafias has been one of the main courses of that view, except in Scarface (Brian de Palma, 1983), the story of Tony Montana (Al Pacino), especially evoked to reflect Miami’s level of violence after Mariel.

To amplify this last perspective, Paramount acquired the copyright for The Corporation (2018), a book by Irish-American T.J. English that follows a non-faction line cultivated by Truman Capote (In Cold Blood, 1966), but not about violence itself but rather migrations and the mafias in the United States.

It’s about a cycle inaugurated by this author in 1990 with The Westies, about the Irish mafia in New York, continuing with Born to Kill (1995) – this time about a Vietnamese gang in the Big Apple’s Chinatown – and 10 years later with Paddy Whacked, a history of Irish gangsterism since the times of the grand famine (1845-1849) until our days.

Havana Nocturne (2008) is English’s first incursion into Cuban themes, in this case the U.S. mafia and its alliance with Fulgencio Batista during the 1950s, those years in which glamour, music and six were mixed without distinction with conspiracy and death.

The experience, without a doubt, became the sting to write The Conspirator, which delves into the Cuban mafia in the United States, a rather very little known subject for the public at large, although with a history that, contrary to what could be assumed, did not begin in 1959 but rather dates back to the second half of the 19th century with the foundation of Ybor City, the arrival from the island of the bolita (a type of illegal numbers game played in Cuba) to that city, and the contraband of alcoholic beverages during Prohibition.

Under the rule of Santo Trafficante Jr., the mafioso who went on to head the family businesses after his father’s death, characters like Cuban American George “Saturday” Zarate, born in Tampa from a cigar-maker father and who stood out for his role in the trafficking of cocaine from South America using Cuba as a springboard to introduce it into the United States, made their debut in the underground world.

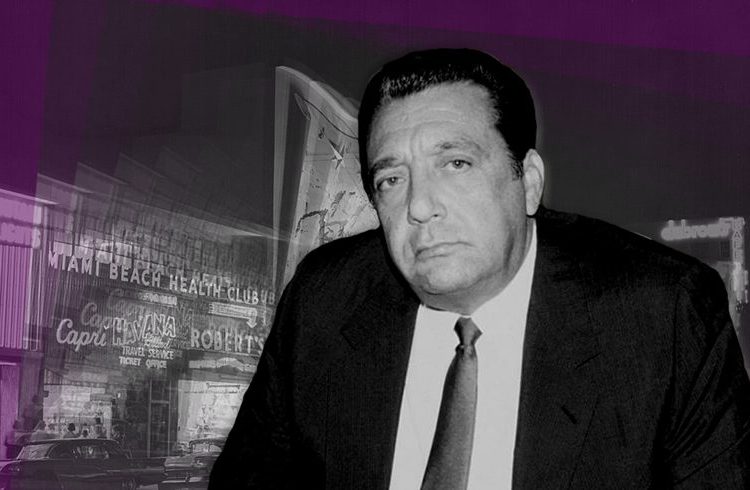

The film’s story is centered on José Miguel Battle (Havana, 1929-South Carolina, 2007), known as “The Godfather” or “Sir Corporation,” a character that will be played by Benicio del Toro, whose connections with all things Cuban come from way back, among other things for having incarnated Che Guevara in a performance that many consider legendary.

Based on his condition of belonging to Batista’s police and participating in the Bay of Pigs adventure, on his return to the United States after being imprisoned for two years Battle started building an empire – built on the “bolita,” drug and blood – between New Jersey, New York and Miami that would get to manage an annual 45 million dollars and to spread its tentacles through South America, Central America and Spain. Of course, with the corresponding and inevitable coordination with politics.

In relation to this English says that the Corporation members were not seen as criminals in their own communities. They were all left destitute by the Revolution and in some way due to the U.S. government’s participation in the island’s domestic affairs. Since they were not here or there, they protected themselves in Miami by holding on to their language and their fierce devotion to the land of their birth.

The 1980s marked the highest point of their achievement: the new century, his fall, that is, his death in a South Carolina prison while he was being transferred to another federal prison with a 20-year sentence.

A peculiarity of this endeavor consists in that the book was bought by Hollywood before being written, an unusual but also esoteric data. According to English, he sent a 120-page draft about the book he was planning to write. He had conceptualized it in his head from beginning to end…and in his experience it’s always worthwhile to write a longer draft. And he added that based on the strength of that draft, the tender began, which put greater pressure on him. It wasn’t an optimum situation in terms of writing the book, and he also started working almost immediately on the script, but he said he was obviously happy that it happened.

The long journey from literature to the image is already there. As is known, a relationship that is as difficult and ungrateful as it is risky and dangerous.

We’ll see if this new Hollywood experience finally measures up.