When Rafael Zarza – October 2, 1944 – was barely a child and was in primary education in La Vibora’s José Miguel Gómez School, he was fascinated by a mural that had been ordered from the brilliant Carlos Enríquez: “the shape of the horses, the way of representing the Mambí independence fighters and the green hues” impressed him. A bit later he felt “truly dazzled” when he stopped before a painting of Armando Menocal that recreated the death of Cuban National Hero Antonio Maceo. There was a third encounter, this time with the landscapes of Miguel Melero: it was in the 1950s and those antecedents – plus a correspondence course in a U.S. school – led him to go to a competitive examination convocation and, finally, he was able to enroll in the prestigious San Alejandro Arts Academy in Havana, from where he graduated in painting and drawing. However, in the academy he did not learn the techniques of engraving, a specialty in which he has developed a resounding and continuous work for more than half a century.

Zarza has been linked to art, especially engraving, for 50 years. First he was a cartographic draftsman and that work gave him the rudiments of the printing techniques and he also learned to engrave in acetate.

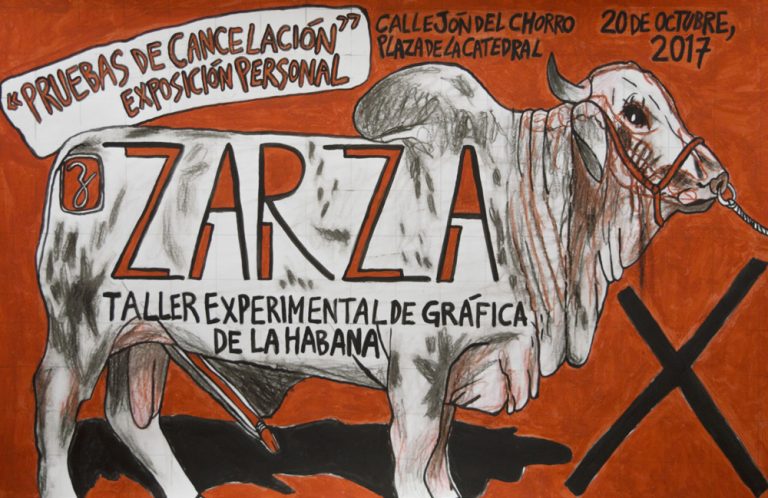

The 1960s came and he started a brief career as a poster artist in the former National Council of Culture, located in the Palace of the Second Corporal, in Old Havana, very close to the Engraving Experimental Workshop: that was precisely the moment of takeoff, because he “discovered” lithography, one of the engraving manifestations that he has made his and which he manages with the dexterity of a maestro, a maestro who has already turned 73 well-carried years of life.

His relationship with stone – lithography’s support or base – was and is so strong that for more than five decades it has been his means of expression and he has been able to dominate the resilient surface of the support as if it were a sheet of paper or a canvas. “I have tried,” he says in a conversation with OnCuba in his studio/workshop in Havana’s El Vedado district, “to eliminate the boundaries between making a painting or a drawing or a lithographic stone; I work as follows: first a place all the colors and the last one is the most intense, which generally is the color black.”

He makes sketches, but he works them the other way around and that way gives each piece a great deal of freshness because of the color: “it honestly fascinates me because with lithography I can obtain the same movement as in a drawing. The only inconvenience is that you have to take into account that the result is the other way around, that is, that you draw it on the right, and it comes out on the left when you print it. You have to foresee that.”

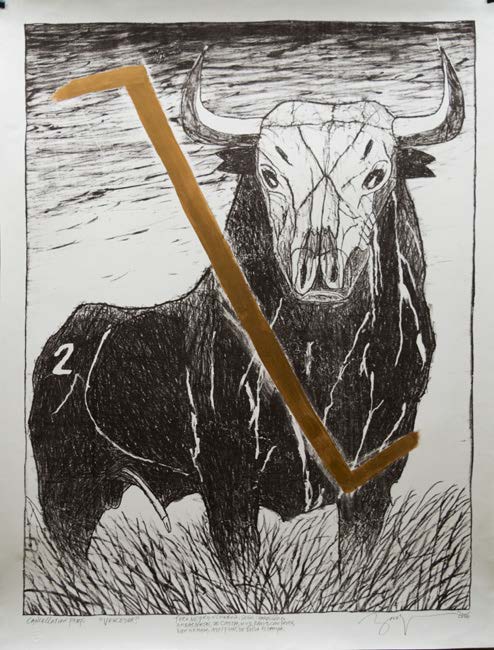

One of the defining moments in the artistic life of Zarza occurred in 1966, when in a Latin American contest summoned by Casa de las Américas he won the Portinari Award for lithography with the piece “El rapto de Europa” (Europe’s Rape). Starting then the taurean theme became almost an obsession and was “the seed of my entire pictorial world, which is characterized by a certain irony,” he affirms.

Zarza’s work undoubtedly has its mark, its seal, and he manages the icon of the bull with an impressive ease and sagacity: one could think that it is a bit repetitive, but if the work is carefully analyzed one becomes aware that the bull or the animal are only the pretext that allows him to delve into the human and the divine. For example, in one of the permanent rooms of the Museum of Fine Arts one finds a work by Zarza that belongs to the “Tauro-retratos” (Taurus-portraits) series: in it he takes the face of a Spanish captain general and turns it into a head of cattle: “when I made the series of the ‘Tauros-retratos’ and ‘Vaca-retratos’ [Cow-portraits] I worked with the faces of the Spanish colonialists, that is to say, persons who were very reluctant and reactionary toward Cuban culture, like Miguel Tacón and other captains general; I usurped their portraits and attacked them and placed horns on them and turned them into oxen, which was their aim with us and I turned Queen Isabella into the “horny cow,” as Martí called her. Cuba never submitted and this series is a way – my way – of paying tribute to all those men and women who, throughout our history, did not give in.”

His meeting with the African continent took place in 1977 and it was a “discovery” because when he came face to face with the masks it opened a world of concerns and it is when he understands that German expressionism and the cubist movement had drunk from that first fountain: “Africa was summed up in the African masks’ smell of the dancer, the taste, the dust…and also elements that make up the Cuban nationality, which is a legacy of the Black continent. I started to study the masks – of great beauty and strength – and to try to combine the African with European influences, and I incorporate all that wealth to my world of cattle and oxen. Most of those masks are used in circumcision rites and that’s why many of them have of phalluses. It could seem a rough topic, but it is full of energy and beauty.”

And although he is known for his solid work as a lithographer, he has also carried out, in parallel, a career as painter: “I am very intimate with the brush, perhaps more withdrawn, but not behind or bogged down,” he confesses. And he immediately starts to show a very thick roll of cloth in which bulls and more bulls of multiple colors start appearing in all possible positions, full of force, haughtiness, energy and bravery. As well as obstinacy, the same that has led Rafael Zarza to stay absolutely faithful to the stone and a devotee of the bull.

LOCALIZATION

Studio/workshop: Calle 29, no. 161, apto 1, e/ C y D, El Vedado, Plaza de la Revolución, Havana, Cuba

Tel.: 7 832 23 01

Email: zartgui@cubarte.cult.cu