Cockfights are very archaic, they date back to antiquity, and in Cuba it is speculated that it was Christopher Columbus who brought the first fighting specimens.

Cuban authors and foreign travelers have described in detail the breeding, training and fights of these singulars birds, and they have referred to their unquestionable roots in our country, despite the government bans, in diverse times, or the serious criticisms of the fights by eminent fellow countrymen. There’s philosopher José Antonio Saco, who in his treaty El juego y la vagancia en Cuba (Gambling and Laziness in Cuba; 1830) alludes briefly to “the pernicious galleries,” a social phenomenon that seemed to him “a perfect democracy,” since they all crowed in the ring, with no social, race, gender or age distinction.

Saco, in the first edition, dealt very little on the issue, since he later recognized that the very Captain General Francisco Dionisio Vives owned a gallery in the lands of La Fuerza Castle, and his warnings about that practice, he admits, “no matter how much temperance and dexterity with which I would have handled the pen, was not able to escape the anathema that would have been fulminated against Memoria sobre la vagancia en Cuba.”

Another suggestive data is that not even during the wars of independence against Spain did these fights stop and thus we have the testimony of Colonel Fermín Valdés Domínguez that the rebels carried, together with their impedimenta and weapon, fighting cocks to pit them in championships: “it a shameful thing but also funny to see the rings in the camps…, during the marches, the ridiculous picture of the soldiers carrying the usual cock by the side of their rifles.”

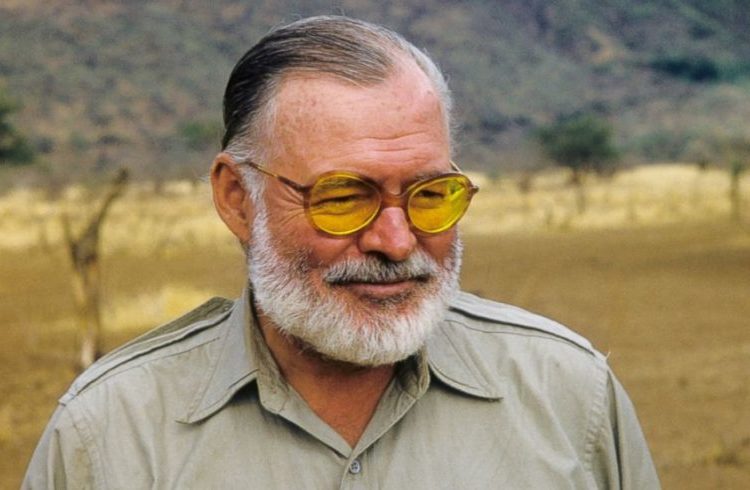

With this preamble, let’s thus say that the author of The Old Man and the Sea, of solid ties with Cuba, in addition to his predilection for fishing and hunting, or for bullfighting, liked cockfights. In a chronicle from 1949, when saying why he lived on the island, he confessed: “It’s not necessary to explain the possibility offered to us of breeding fighting cocks, training them and participating in the competition wherever they are organized, since it’s a legal matter. It is one of the reasons I live on that island.”

Norberto Fuentes tells us that in his Finca Vigía, in San Francisco de Paula, Hemingway ordered that a small cockfighting ring be built and he partnered with José Herrera, alias Pichilo, who cared for his specimens and was at his side since 1942. There he used to breed some 20 cocks to fight in competitions. Pichilo affirmed that Hemingway liked to bet a lot, but his end was not profits, and he mentioned one of his phrases: “What I like is watching the fight.”

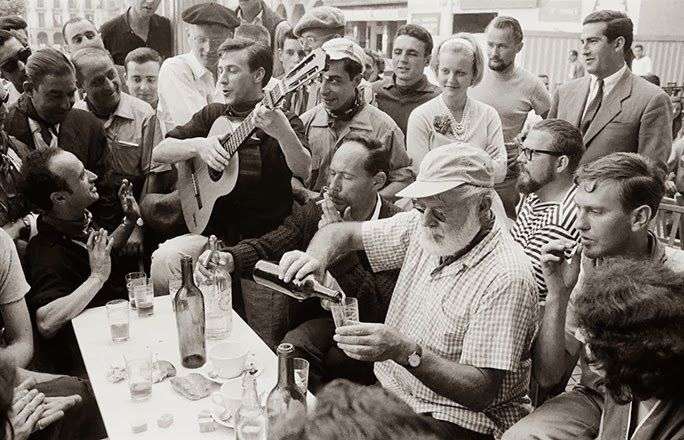

When he won his fights he would invite all those present to the bar of the ring in question and great amounts of alcohol were consumed. The writer warned that he would drink until he was blue in the face, but that they shouldn’t be a pest: “I drink and I get drunk every day, but I don’t bother anybody.” The idea was to drink with the moral of the story included.

The passion for cockfighting, so related to Cubans from all times, also infected Hemingway, to the point of recognizing that it was one of the reasons, not the only one, of course, why he chose Cuba as his home for many years.