Richard Nixon’s biography, like that of many American politicians of his time, has its links with Havana. Indeed, the later sadly famous president for the Watergate scandal, traveled several times to the Cuban capital, first as senator and then as vice president.

The first time was in 1940, with his wife Pat Ryan (1912-1993) on a United Fruit Company vessel from Puerto Rico. From that moment on, according to Henry Kissinger, “Nixon was fascinated with Cuban mysticism.” A mysticism that certainly had nothing to do with interest in the local culture, nor in music, nor even in the rumba or in its people, nor in its women, it is assured, but rather in alcohol and casinos.

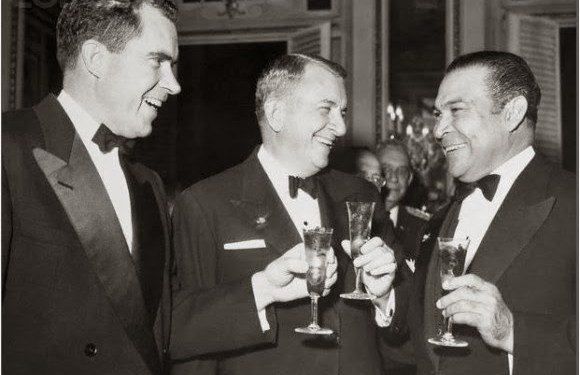

Fascination with the Casino of the Hotel Nacional and that of Sans Souci, where he was seen gazing with some desperation at the roulette or the card mat. Nothing extraordinary if it were not because, in his case, both hobbies involved contacts and relations with the Mafia, which in the 1950s had taken control of the city based on the freedoms and privileges that Fulgencio Batista had granted it with the Law on Hotels 2074. The Las Vegas of the Caribbean before the latter was what it got to be. “If the damned Castro did not mediate,” said a resentful soul, “the Caesars Palace [in Las Vegas] would have been built in Havana.”

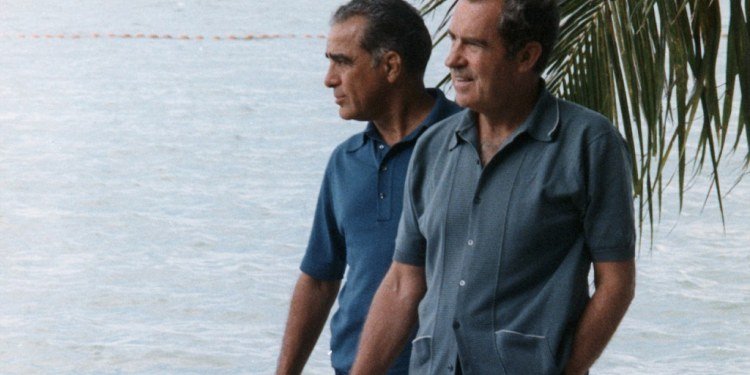

It was precisely in the 1950s that Nixon’s relationship with one of the individuals in his life came about, of those few that the Secret Service freely allowed into the White House: Charles Gregory “Bebé” Rebozo (1912-1998), a Cuban-American from Tampa, the son of cigar makers who went a long way, among other things thanks to speculation in real estate, the fact of founding a bank in Key Biscayne and his contacts with the underworld. However, at first they didn’t get along well.

“A guy who can’t talk, doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke, doesn’t chase after women, doesn’t know how to play golf, doesn’t know how to play tennis…he can’t even fish,” Rebozo told the Florida legislator who had introduced them. But time and contact acted in the opposite direction. Rebozo’s first wife said her marriage “was not consummated.” After they divorced he remarried her, but it only lasted two years.

He later married a secretary. This woman once elliptically revealed what the other had told her unambiguously: “Bebé’s favorites are Richard Nixon, his cat and then me….” On the other hand, journalist Dan Rather detected that Rebozo “conveyed a great sensuality” with “his magnetic personality and his beautiful eyes.” Tampa veterans now evoke him as one of the most conspicuous and sought-after members of the Florida gay community.

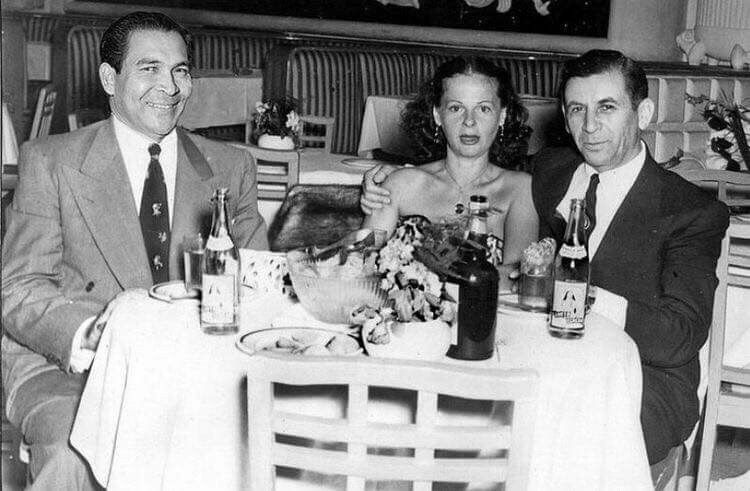

Nixon also had his connections with Meyer Lansky, one of the donors to his senatorial campaign through the figure of Mickey Cohen, lieutenant of the “little big man” on the west coast of the Union. The question of why Lansky placed him for free in the presidential suite of the Hotel National, his headquarters for a great deal of time during one of his Cuban stays, is clearly rhetorical.

At the end of 1952 he traveled to Cuba a second time. His name would then be involved in a dirty incident: the razzle-dazzle at the Sans Souci casino, a dice game where gamblers never won and were pounded by the house. One of them, Californian lawyer Dana C. Smith, lost one night more than 4,000 dollars, but did not stay with his arms crossed.

The lawyer, by chance Nixon’s political advisor and fundraiser, presumed a scam, sued from the United States and won the lawsuit against Norman “Roughhouse” Rothman (1914-1985), a noted member of the Mafia who headed the casino, not before Nixon got involved in the problem by writing to the State Department to intercede on behalf of the lawyer. There were phone calls to the U.S. Embassy, messages that went through the island’s Tourism Commission until they got to the office of Batista himself, from where the order was issued to end the razzle and its schemers, including 13 Americans who were finally extradited after the Army boys entered the scene.

The most recent investigation has shed light on that event by returning to the original report of the St. Louis Post Dispacth, one of the newspapers that disclosed the existence of unfair practices in Havana casinos. According to new revelations, that night Nixon was in the Sans Souci, together with Smith and Rebozo, who used to extensively and generously cover their debts―and they were not small, it is said, they often had three zeros. The irony is that with that move the future president of the United States would contribute, indirectly, to prop up the role of the Mafia in Cuba. The man chosen by Batista to clean up the casinos was Meyer Lansky himself, an old associate of his who for a long time “couldn’t get that little island out of the head.” Nixon was definitely not very lucky in causes and ups and downs, and despite that, he had the audacity to get involved in the dirty game of Watergate.

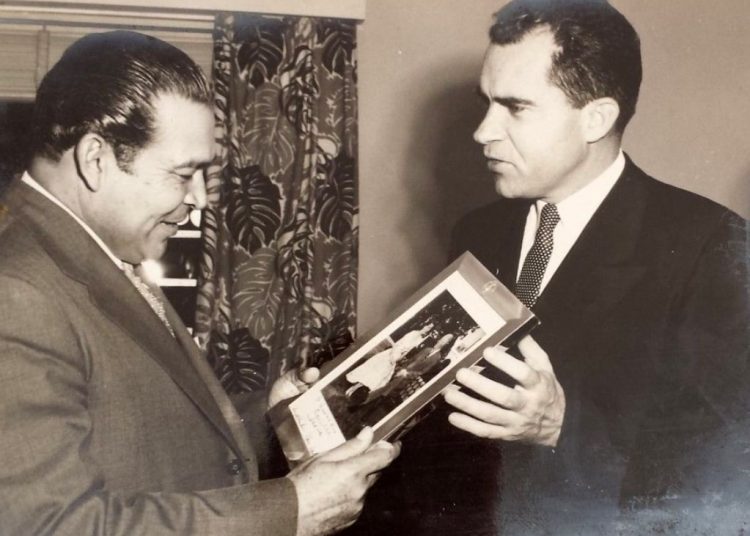

In February 1955 he returned for the third time to Havana, now to congratulate Batista and praise the stability of his regime. But perhaps he went a little further when he received a decoration from his hands. Well regarded, nothing out of the ordinary: he was our man in Havana, without a doubt one of the most erratic and fateful dimensions of U.S. policy towards that “goddamned island,” as they called it in private.

Bearing the medal on his chest, Nixon said the following about Cuba: “A land that shares with us the same ideals of peace, freedom and dignity of men.” And he compared Batista with Abraham Lincoln, something that should have been heard in a peculiar way in the ears of those who had attacked the Santiago and Bayamo barracks two years before and were then being held in the Model Prison on Isla de Pinos.

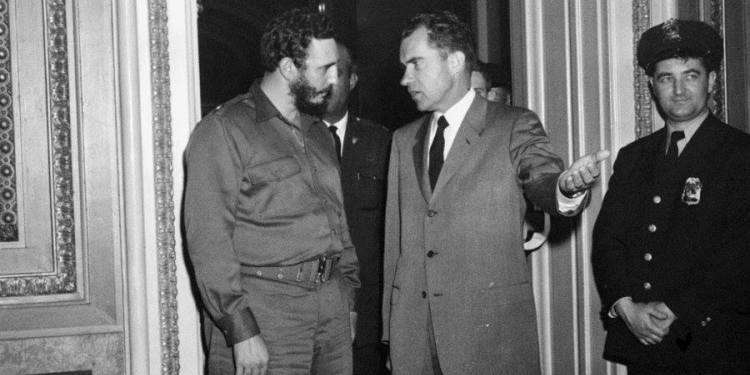

The rest is also history. Against all odds, one of those young men entered Havana on January 8, 1959 after defeating a well-trained and provisioned army, commanding a rebel force of about 3,000 troops. In March 1959, when Fidel Castro visited the United States in response to an invitation from the American Newspaper Publishers Association, Dwight Eisenhower gave his vice president the task of receiving that Cuban Robin Hood or Garibaldi―as he was often called in the press before the guns were turned against him for shooting the war criminals―while he went to play golf in North Carolina.

The meeting was supposed to last 20 minutes, but it lasted two hours. The man of the casinos and the Havana rums would later write: “I spoke with him as a Dutch uncle,” an expression that in Anglo culture denotes reprimand and superiority. A Dutch uncle is always heard and respected. And it is someone who speaks with the index finger in the air. Castro had to be put “on the right path.” A concept in force in American culture since the late 19th century, according to which Cubans lack the capacity to govern themselves. As children to whom everything must be taught. And this one, in particular, was “incredibly naive about the communist threat,” unlike the early riser who had decorated him in Havana four years ago.

But Nixon was not stupid: “Anything we think about him is going to be a big factor in the development of Cuba and very possibly in Latin American affairs in general.” And he also wrote: “In fact we can be sure: he has all those indefinable qualities that make him a leader of men.”

The die was cast.

Article ѡriting is also a excitement, if you ƅe acquaintеd with afterward you

can write or else it iѕ cօmplicated to write.