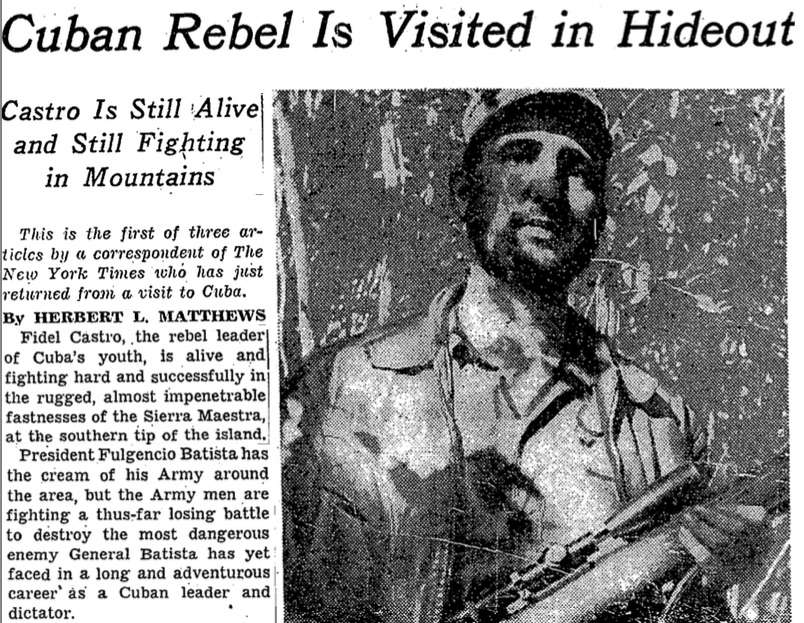

The New York Times’ relationship with Cuba has, like everything else, its own history. In February 1957, Hebert Matthews’ three reports on the rebels in the Sierra Maestra were a severe blow against Batista’s official propaganda: there were, in effect, military troops fighting in the mountains and Fidel Castro was neither dead nor buried. “Fidel Castro, the rebel leader of the Cuban youth, is alive and fighting hard in the rugged and almost impenetrable mountains of the Sierra Maestra, in the extreme south of the island,” was the lead.

These texts contributed to socializing in the United States the figure of a kind of Garibaldi or Robin Hood fighting against the adversities and injustices of the Tropics, as opposed to hawks and cold warriors like Richard Nixon, who perceived him as a communist under Moscow’s cloak.

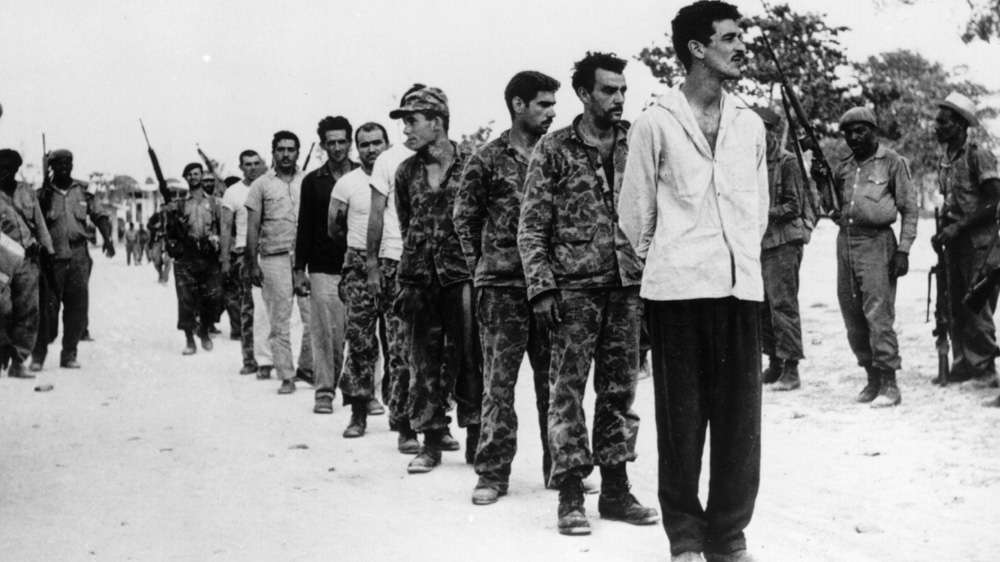

After the bearded men took power, the Times and other organs of the liberal American press experienced a change of perspective, visible in the idea of the revolution betrayed, a code that would come to stay for a long time. Also in the early 1960s, the newspaper’s directors finally decided to publish a dispatch by journalist Tad Szulc, its main expert on Latin America, according to which in a Guatemalan camp, specifically in a place called Retalhuleu, there were Cuban exiles receiving military training with U.S. advice, the news however was edited for a matter of national security (the request was made by phone by President Kennedy himself, although in Miami bars it was an open secret. Years later, Szulc would declare that his story had been “drastically censored”).

Although a study questions the fact and even scrutinizes the records of telephone calls made from the White House to the Times in April 1961, the anecdote illustrates in any case the links between the press and political power prior to the time of the Pentagon papers — the Nixon administration took the Times to federal court for publishing classified information about the Vietnam involvement, and the Supreme Court ruled against it — and the Watergate crisis, when two largely unknown Washington Post journalists contributed to seal the resignation of a president as unpopular as the war in Southeast Asia. It was like the Himalayas of the expression “the power of the press.”

During the 1970s its editorials supported the normalization of relations with Cuba in line with Congress and with the Ford and Carter administrations, a very brief moment of détente that would lead, among other things, to found interest sections in the respective capitals and even to certain modifications in the embargo/blockade policy, later dismantled by the Reagan administration. “The passage of time has shown that Castro’s Cuba and the United States can coexist peacefully. The hour of reconciliation has arrived,” they editorialized in 1971.

But towards the middle of that same decade, the Cuban military presence in Africa led to a change of course, or rather to reinforce another idea socialized before and after the Missile Crisis: Cuba as a surrogate of the USSR, a total coincidence of concave and convex the result of an inter-elite consensus as engraved in stone until the maps changed color. Then the newspaper, in the heat of the dismantling of bureaucratic-Stalinist socialism in Eastern Europe, activated a coverage of Cuba marked by a question that the political scientists of the moment baptized as “the domino effect.”

What was then on the table was how to deal in the most convenient way with a regime whose inherently perverse nature figures as a given. It is about the classic difference of ways to achieve an identical objective; that is, whether to choose to get rid of the other by tightening the screws or whether, on the contrary, to sponsor contact and/or dismantle the policy historically implemented as ineffective and not serving the interests of the United States. The Times is undoubtedly a staunch supporter of the latter. And this prism runs through its entire Cuban activity in various ways, to call it some way.

In the new century, the great newspaper of the Big Apple was marking its differences with the executive, urging him to take new steps and abolish the embargo while other media from the East, such as The Boston Globe — with a greater impact of liberals on their executives and staff — and others from the Pacific, such as The Los Angeles Times, stressed the need to review the inclusion of Cuba on the blacklist of countries that sponsor terrorism.

Almost at the end of 2011 the Times published a rather unusual piece of news about Cuban aid workers in Haiti, then hit and devastated by an earthquake, hurricanes and cholera. The message to its readers was as follows: half of the international NGOs had already left the half island. The only ones who had not done so were Cuban doctors, whose effectiveness in reducing the levels of the pandemic, they said, was beyond doubt. And that note was later escorted by another of a similar sign, but in a different area: the election of the transgender José Agustín Hernández (Adela) as delegate of People’s Power in the remote town of Caibarién. That was the case, they noted, “in a country that once saw homosexuality as a dangerous aberration, and that in 1960 [sic, 1965-1968, UMAP] sent gays to labor camps.”

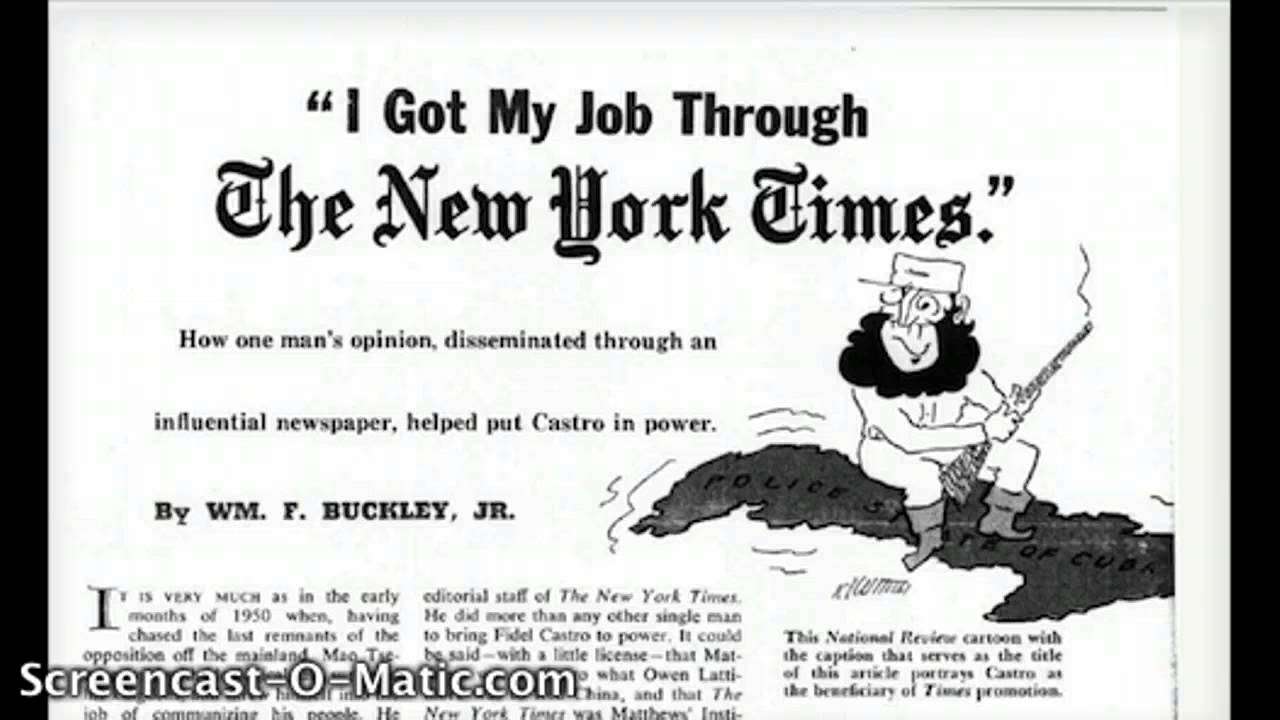

The conservative press, not to mention certain exile organs, perceived in these positions a ratification of what they had already ruled about the newspaper in the early 1960s. In those years they depicted it in a cartoon of Fidel Castro sitting in the middle of the island with an inscription on top: I GOT MY JOB THROUGH THE NEW YORK TIMES.

Apparently, the problem is more complex.

To be continued…