Private jet

These days flying, using the services of an airline, seems like an extraordinary and rare privilege. Now traveling on board a plane with hundreds of available seats but with only 11 people on board, as in American Airlines Flight 743 on Tuesday, March 24, gives the feeling that one is on a private jet. Or that you’ve gotten permission to do something forbidden, something already remote, although just a month ago the traffic of millions of people from point A to point B in almost the entire planet was still natural. The pandemic has filled us with ships in port and aircraft on land. Nothing sets sail, nothing takes off.

These days the world seems like a stage without actors, both open and closed spaces intended for large gatherings. In life, it is our ghosts that fill avenues, squares and stadiums.

Miami International Airport, where I made a stopover on the way to José Martí, was a set of large empty lounges. After witnessing the movement of thousands of people, the shops, the movement of luggage, welcomes and farewells, finding that scene of silence, corridors without passers-by and empty seats was a dystopian experience.

The Boeing was light. Perhaps it was my imagination, but I felt that it took flight easier than normal and, then, that it floated in the air.

However, when crossing the Straits, the water wall, the invisible iron curtain between Cuba and the United States, from the empire to the socialist homeland, or from the land of freedom to the totalitarian regime, the 45 minutes seemed longer. These are rare days of elastic time.

“Welcome to the homeland” and congratulations

Once we touched down in Havana and the plane reached the tunnel that leads to the airport gate, Cuban soil covered by a worn-out and stained carpet awaited us. So was the table where two people wrote down our 11 names and gave us a bus pass with a number. From there we went to wait for our luggage: the only suitcase allowed, weighing 23 kilograms.

The previous night it had been announced on Cuban television that only one suitcase per person would be allowed. I had been in the United States for several months, and returning to the “situation of shortage” and in the midst of an emergency like this, every pin that I or anyone could “enter the country” would be necessary and used. But it was not possible.

“There isn’t even a place to pee here,” a woman from Holguín shouted to her son by telephone from the room where we waited for a transport towards the unknown, so that he and everyone would know. “When they take me where-they-take-me, I’ll call to tell you if I’m alive or dead.”

The woman works as a nanny in the United States but thought it would be better to pass this crisis in her Cuban home. We left together from Phoenix, Arizona; I heard her crying at Sky Harbor: she had left two children behind, and their mother in Florida owes money and is out of a job.

There is no bathroom or drinking water in the waiting room where we are. But the preferred theme among newcomers is the sacrifice of the second suitcase. A man from Matanzas managed to bring a pellet shotgun anyway, to “shoot a little at the cans.” “Things are now bad and that’s it, you have to look for something to do for fun.” He bought it in a sale at Walmart, less than 60 dollars because it doesn’t have a telescopic sight.

In the United States, there were not only long lines in food establishments: the sale of firearms and ammunition has shot up, it’s worth saying. A Tulsa, Oklahoma, vendor reported an 800 percent increase in purchases. These suppliers have been exempted from total closure, using the argument of “safety.”

According to AFP, most are first-time buyers and have no preferences: they take whatever is available. Some do it encouraged by the same plan to shoot at cans in the midst of their boredom; but most are scared, fueled by apocalyptic paranoia that the State is collapsing, society is in chaos, and one group is imposing itself by force, as in Blindness―even if they don’t know it―or they simply foresee social instability as the pandemic crisis continues to escalate. There are all kinds of theories and projections. And a market that gets away with it.

Doris, from Alamar, took food out of her luggage and left it in Miami, but kept the stroller for her 3-year-old grandson. Transcendental decisions like that had to be made: food vs. stroller.

The first time I returned to Cuba I wondered if no one had named a type of phobia to pack luggage for the return to the island. We need everything, anything, a band-aid, a TV set, a package of coffee, some pills. Someone may question Doris’s choice, but no one can contest her decision “when it comes to the child.”

“Hand over,” the Customs officer said to me when asking for my passport. I thought about saying “Take it” but I stopped imitating her. I thanked her kindly and wished her a good day but she didn’t look at me.

Once we paid the import tax, they gave us a snack, without saying a word. Then we received the instruction to stop and wait for us to be called according to the province of our homes. Almost an hour had passed since we had left the plane.

The measure to isolate the newcomers was applied as of Tuesday, March 24, the day of my arrival, because the self-isolation order was not working. The dozens of contacts of those infected who had come from abroad show that once in Cuba and before having symptoms, they did not limit their meetings with family and friends.

The entry or exit from the air terminal was not allowed, except for the personnel involved in the transfer operation, and us, of course.

We finally found out that those from Havana would go to Cotorro. Once the signal was given, we carried our luggage to the bus, despite being surrounded by idle people. They said they had instructions not to interact with us or our bags, which had already been disinfected twice with a jet of chlorinated water.

During the journey one who knows the municipality “like the back of his hand” criticized the inefficiency of the route, even without knowing exactly where we were going. He jokingly fantasized about an escape plan. Earlier he had asked if we wanted him to hijack the bus, at a time when the driver got off. All laughed, behind facemasks.

Six persons had escaped from their isolation center in Sancti Spíritus and are facing two criminal charges. They say that one tested positive for the virus.

After a slightly bumpy ride, guided by a police patrol and attracting attention in the still crowded streets, the bus arrived at the Fermín Valdés Domínguez student residence.

A doctor greeted us and gave us details about meal times and more. “Honey, bring that over here, nobody is going to take it from you,” said a nurse to a lady who kept her packages by her side, in the sun and on the other side of the small street at the entrance.

There are about four buildings of up to three floors, connected by corridors with granite floors. There is air conditioning but the indication is that the spaces be ventilated only through the windows. There’s a breeze, but there are mosquitoes, and to cover ourselves we only have a bedspread. Between mosquitoes and heat, most choose heat.

We begin to mix with other travelers. Some countries of origin do not arouse much congeniality among the group. The United States the least, after Italy and Spain.

In cubicles of 12 people distributed in bunks about three meters away from each other, video calls didn’t take long to start. Twenty-two voices could be heard at once. No one was wearing headphones. I, without a line or Internet, had time to observe them.

We are about 300, as someone on duty told me. The staff devotes itself to preparing and serving us breakfast, lunch and supper, they risk being in contact with people who come from all over the world. They will have to remain 14 more days in isolation after our departure from the residence.

The health workers in charge of the place have little capacity to impose a regimen of discipline, and for each of us separately it is difficult to have any influence on the group in general. Most self-impose a distancing routine; but there are also people who, determined to spend these days as if they were on a recreational retreat, crowd, shout, have a good time.

Until March 30, there were 2,837 people―73 foreigners―admitted for clinical-epidemiological surveillance in this type of center, used for the time being for this isolation.

The bathrooms are mixed: men and women of different ages can bathe in the same showers, which among them have only one or two drains. They use the same toilets and the same personal hygiene space. One lady laughed as she had just seen a naked man, another woman was seen in a bra. That one doesn’t think it’s funny.

A third cries. She throws herself on the floor and says she’s not going to stay here. She talks on the phone all the time. Finally, she stays and little by little her mood improves. I’m seeing everything, as if I were reporting and I was not, as I am, one more. Feeling in that position unintentionally gives me the advantage of placing myself on another plane, I distance myself from my own situation.

In my cubicle we are all women, from the Dominican Republic, Russia and the United States. Some just bring winter clothes; no one was prepared to come directly from the plane to the internment. Others who come from Nicaragua complain about having to share space with people who come from countries with higher contagion rates. “Where we come from there are two cases!”

We are surrounded by coconut trees, palms and royal poinciana trees full of birds. From my bed by the window I see and hear cows, sparrows, and bee hummingbirds. After an overexposure to the news, the silence and disinformation in which we immerse ourselves in this school in the countryside hides the crisis. Nature runs its course apart from us, from our anguish and instills a strange peace; things regain some meaning. It seems impossible after so much alteration of what for us is normal.

Let the sun keep coming out, the breeze blowing, the rain falling, and the birds flying, making their nests or whatever occupies them in their daily hustle and bustle here and there, send a reassuring autopilot signal that indeed order beyond human control is, in spite of everything, ensuring that this world continues to rotate.

Someone comments that a bus full of people who came from Spain is on the way. “Oh no!” says a woman who comes from Russia. When she was going to enter, others said “Oh no!” too. When I arrived and they asked where I was coming from and I said “United States” they said “Dear me!”

At night there is an update of soap operas. Those who were out of Cuba for a month update those who had been several months. I was not very aware, but I know that the character of Gloria Pires donated an organ to a daughter who had rejected her, there is some sordid story of mother and daughter unknowingly sharing the same couple, and there are, properly, illegitimate children and hidden fortunes.

They don’t know it, but in their company on this first day of confinement under sanitary surveillance I turned 31 years old.

In another world and its pandemic

On March 26, in the dining room I met a photographer I know on Facebook. We got to talking and we got to criticizing the social networks when he told me that someone was trying to demonstrate his point that Elpidio Valdés was a sexist character. I ask him what all that was about and that’s how I found out that Juan Padrón had died on March 24.

The next day I learned that French cartoonist Uderzo, “father” of Asterix and Obelix, had also died on my birthday. When I studied at the Alliance Française we could get the book we wanted from the media library. I always took out Asterix and nothing else.

After exploring some options, I came up with the idea of recharging my bedside neighbor’s cell phone so I could use it as a Wi-Fi point. There are two networks at this school, but we don’t have access to the password.

As soon as I connect to the Internet, the torrent of information of all kinds opens: quality and precarious, trustworthy and fake; with the limitations of an expensive connection, with blockades and not always fast. I find out that an Italian nurse committed suicide. She worked in intensive care, tested positive for the virus and decided to kill herself. One in Venice too.

I know through the Cuban press the protocol for handling corpses in the country. The bodies will go into a zippered bag and there will be no contact with them. The decision to bury or cremate them will be up to the families.

I know that my roommate from Montenegro has already left Phoenix and is in Podgorica, also isolated, in a tiny room with three other people, prevented from leaving. I think I’m not that bad off after all. Especially now that we were moved from the cubicle of 12 to one of 4 with the same space, after many complaints about the conditions we were in, and that someone filmed and published the scandal caused by a group that came from Europe, for the same reasons.

Since then the staff has insisted on being sweet, caring and monitoring have become much more systematic, including more temperature control and constant changing of the facemasks.

Time is so condensed now that it can be kneaded. You could get eight soap operas out of it by inventing layers and layers of reality in the middle of this pause, using as many possible plots, so many events to take place.

For example, I came up with one: it is the story of two who meet in an isolation center. Only the eyes have been seen from above the facemask; they talk a lot but two meters away, and they only have the makeup and adornments that a hand luggage has allowed them, poorly matched garments, the only shoes…. When the time comes they won’t be able to caress or touch each other, much less kiss. Pure containment.

“Name and temperature, girls,” the nurse asks us a few minutes after leaving us with the thermometers on. Thirty-seven degrees are enough to be referred to another center. There would be no use lying, they check.

A doctor passes by with two bags, one for used facemasks, one for clean ones. “Watch out you don’t get confused, bro,” one jokingly provokes him.

A young woman likes to guess things about the person who previously used her facemask, if he/she smoked, if he/she ate meat or something that was greasy, if he/she used perfume. I always smell the same thing from the ironing. I have no complaints.

They put soaps in the bathroom sinks and reduced the concentration of people per cubicle. Even the dining room trays look cleaner. Everyone has calmed down; some are even happy. The atmosphere of insurrection of the first two nights has been completely diluted.

Moving to another block has had other advantages for me and the other three that came. We left behind a group of bullies who dominated the floor, bathroom included. They played loud music and we could hear from “Bajanda” to “Another Brick in the Wall.” I like both songs, but I don’t miss them.

When they saw us leave with our bundles they even made a couple of dirty jokes. It was predictable, and it’s not in short supply. Today a young woman from a window asked two men who were sitting very close on the ground floor to distance each other, please 2 meters. “We have two meters, yes…between the two!” They replied.

On our floor there are now only two men.

Another language

I learned that my mom started making facemasks by hand. I imagine her with needle and thread, engaged in sewing with the sweet face that she puts on when she does this. “I’m like Penelope,” she says, but without undoing what she sewed at night.

Facemasks, isolated, quarantine, infections, rapid tests…are the words of the language these days here, the virulent vocabulary that is heard at random if you walk down a hallway, or you hear the person in the next room talking loudly on the cell phone.

All kinds of rumors circulate from room to room, from sudden changes in the lunch schedule to alleged confirmations of last-minute contagion. The sources are most diverse, almost always direct and of unquestionable attributed authority. As they say in Spain, “everyone here has a buddy.”

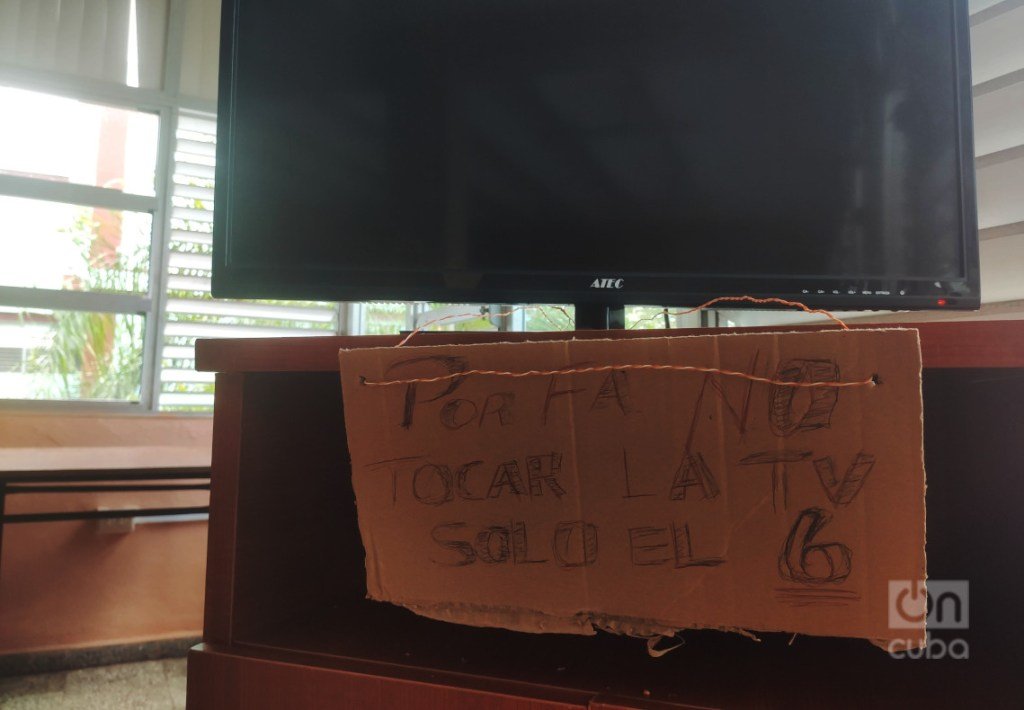

We follow on Worldometers the coronavirus cases in the United States, in batches of thousands. The National Television Newscast that we see on the floor’s collective television, keeping distance between us, also brings us the bad news of “the rich northern nation” and “the developed Europe,” forcing a certain vengeful irony against capitalism.

Life as movement, quarantine as death

I dreamed about my dad again. This time we weren’t talking, he was lying in the room where I grew up, sleeping in his usual position. I wanted to be with him to take care of him. The first night I spent in isolation here I dreamed that we were at a beach, in Caleta Buena, and he leaned back to float on the water. I was holding him by the back. At that moment I started to cry and he asked me if I couldn’t sleep, I told him that it wasn’t that, but that I really missed him. My dad answered me “well, no human being will be with you all your life, just so you know.” “Wow, sounds like something he would say,” my sister confirmed when I told her the other day by chat.

Life is fragile, the only thing it takes to die is to be alive, death is part of life, death is natural, and so on. They were things that he used to say. But we have never dealt with that truth on a daily basis as in the past few months. That it’s enough to touch someone once so that something that we cannot even see unleashes an important lethal effect, and that our daily routine has been so violently disorganized.

The confinement makes me think of inmates, the hidden Jews, the zoos and the aquariums, in which they are in absolute rest, with the differences of each case. I think of “Letter to a young lady in Paris,” of how many bunnies would be born in this universal seclusion, how many hairs will grow, how much beard, how many hours will pile up, how much muscle will be stunted, how much money will not be produced, earned or spent, money-stopped-is-dead-money, so much tiredness from resting. I wonder what rarefied world is inhabited by those who cannot seclude themselves or completely or incompletely vegetate.

There are several things in common between this home confinement and death, especially fantasizing about some form of post-mortem consciousness that must resemble what we feel now when we think of our pre-pandemic life. What we had perhaps was not perfect, but it was close, like the song says―it seems to us now―to what we simply dreamed of.

We have taken for granted many things that would be a luxury today: freedom of movement, visiting people, filling places, eating and drinking in company, listening to music or dancing together, seeing each other without a screen, touching each other.… There were very simple plans and very complex plans, to be carried out in the short, medium or long term, tourism or emigration trips, weddings, baptisms and birthdays, with more or less resources, produced with better or worse resources, with many guests or with few. Some have been postponed, and others have had to be canceled.

If we could have known, if we could have taken advantage, if we had understood how all this could end suddenly, without warning.

Where were the in-between hours going, and where are all these overlapping cycles going now? Life is surely not this, but was it that? The mechanism, the alarm that sounds in the morning and is reprogrammed at night.

“It’s already later than you think,” “Life is what happens to you while you are busy making other plans,” “I laugh, because tomorrow maybe there’s a funeral, a panther bite in my most intimate self”… everyone has said it their own way.

Perhaps with this essay the lesson will be learned the hard way, that it’s still not the worst because, for most, it’s still an essay. Nothing and no one is forever. And it is that silent destruction, that transience, that makes us valuable. We are because we are not eternal.

Numbers and letters

The deaths from the coronavirus have been older than people. “Two more died,” someone says, and the essential question doesn’t take long in coming: “How old were they?” “Do you know the ages of those from Italy?” The drama is estimated in how old the dead were. The number enters your head and then comes the quick review: how old is my mom, how old is my grandfather…how old am I.

A friend from the Philippines knows two who died, a journalist and a teacher, and another who has just tested positive, a doctor. For her, the pandemic has manifested itself in a very specific way. This is how I also imagine it is for Clara Paone, my Italian doctor friend, who for weeks has been caring for patients with COVID-19 in Bologna.

Today the gentleman in Turin died. He owned the bar on the ground floor of my boyfriend’s company. The company circulated a message among all, giving the news and expressing condolences. People used to have lunch there, and to have a drink and talk after work. I like those Italian places where the owner is the one who takes care of you, as if you were at home. And if the owner is old, it means that for a long time many people had been visiting his home. Or that’s what it seems, and that’s enough.

Fausto Lazzaretti is the first person to die of the coronavirus about whom we have such a direct reference. And it’s barely necessary for this tragedy to cease being just a number, because there is a time when 694 already seemed equal to 873 and then 11,000. But it’s enough that a single one of those units stops being encoded in digits and becomes a combination of letters, a face with a story, so that the account adjusts more to this truth.

Routine

It’s raining. Here we hope that the stray dog that runs around the dining room waiting for leftovers has a place to shelter with her puppies. Me, with a week of isolation away from home. I have seven days left.

Every day I apply water and soap thoroughly and put on some lotion afterwards, to alleviate a little my skin’s dehydration, only until the next hand wash. It’s such a repetitive act that it now seems permanent. Hand washing, lotion, washing…. At 9, applause for the doctors, also here. But that doesn’t tire us like washing our hands.

It is the moment of maximum connection that we can have, being part of a network, of something bigger and more numerous than ourselves, now that a virus forces us to impose distance. We are because we are not eternal, and also because we are more than one.

***

Postscript…

This afternoon of April 1 they have started using the rapid test on the people who are in this isolation throughout Cuba.

The test allows us to know, through a blood sample, if we are infected with the coronavirus.

This test detects in less than half an hour whether our immune systems have responded to the infection by generating antibodies.

The good news is that my test was negative as well as that of those who accompany me in this isolation.