When in January of this year the Family Attention System (SAF) put into effect a new price scale, raising the value of its menus up to 15 times, Julio Antonio Manresa had been six months requesting a place in one of the system’s dining rooms in Ciego de Ávila, his municipality of residence.

The lack of places, first; and then, the mobilization to face the pandemic of the social workers who cared for his community, had closed the doors for him. “Don’t despair, Grandpa. The lists are organized again every beginning of the year and we will surely find a way to accommodate you,” they had encouraged him, however.

Julio Antonio didn’t even have to wait for the promised review of the list. Midway through the second week of January, one of the social workers handling his case visited him to find out if he was still interested in joining the SAF. “It’s that a lot of diners have dropped out after the prices went up,” she told him.

Regarding the Family Attention System, the Monetary Reorganization policy in Cuba proposed the elimination of subsidies as a premise. Since January 1 of this year, the State only assumes the cost of the menus consumed by people receiving Social Assistance (15.9% of the beneficiaries of the program).

The exponential increase in the bill made thousands of people stop going to the dining rooms, or did it fewer days a week and only to buy a part of what was offered. Ciego de Ávila was the second province with the highest amount of absences (46.7% of the census), although the phenomenon spread throughout the country.

Despite these new circumstances, Julio Antonio had not changed his mind. Numbers in hand, the price still seemed convenient. “Where can you find lunch and supper for 20 or 25 pesos a day? At home I try to improve it a bit with what my daughter, who lives nearby, sends me or with what I prepare myself, but it isn’t the same as having to look for things and start cooking from scratch. Just in liquefied gas and ingredients, how much would we be talking about?”

Following a government-ordered cut down in prices in mid-January, the bulk of SAF beneficiaries chose to retain their membership. Among the more than 76,000 people who regularly go to the dining rooms (about half are retirees with low incomes) Julio Antonio’s same utilitarian logic prevailed, despite the fact that the price increase did not bring about improvements in quality and variety of meals, as had been announced.

https://oncubanews.1eye.us/ecos/pobreza-y-desamparo-en-la-coyuntura-cubana/

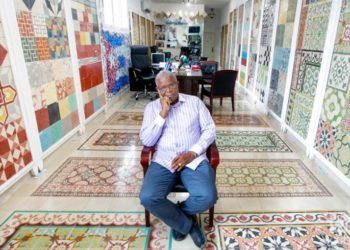

With a pension that is around 2,100 pesos, and occasional income from “a little job on the side,” Julio Antonio has in his favor living in his own house, “to which nothing has to be done in terms of construction,” and suffering just from “quite controlled” hypertension. His biggest concerns would be having to repair some household appliance (“because of how expensive the repairs are”) or being bedridden (“it’s very hard to become a burden for one’s family”). Compared to others, at 73, he is a lucky man.

Older and more vulnerable

At some point, towards 2040, for the first time in its history Latin America will have more elderly than children. The region should spend the next few decades preparing to deal with “changes in health care, new requirements for social security, the form of family relationships, and the creation of support networks,” the Economic Commission for Latin America has warned.

Cuba arrived at that stage 30 years in advance. In 2010, the proportion between the elderly and children shifted in favor of the former, initiating a seemingly irreversible trend. The projections of the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI) suggest that from now to 2050 the number of Cubans aged 60 or over will double, reaching almost 40% of the national register. If the forecasts come true, our country would become the ninth in the world with the highest percentage of elderly population.

But unlike the other nations that surpass it in that list, Cuba is a society that has been characterized by having a markedly negative migratory balance and an “underdeveloped” economy.

The “demographic aging in industrialized countries was accompanied by an economic takeoff (… sustained) in high productivity technologies, which made possible greater production of economic goods and high quality services,” professors Ana María Ramos and Mirtha Juliana Yordi, from the Ignacio Agramonte Loynaz University of Camagüey, counter.

An research by them, published in 2016, emphasizes the “pressing challenges” faced by the island’s health and social security systems. “Family networks are overstretched…as demand for institutions grows for long-term care; as well as specialized health services.”

A health contingency situation would find Cuba in a disadvantageous position compared to societies with a “less aged” demographic pyramid, like any of the others in the Caribbean basin.

Age and its consequent comorbidities are a notable handicap when it comes to COVID-19. According to data from the Cuban Ministry of Public Health, during the first three weeks of August — the month with the highest fatality since the beginning of the pandemic — 1,723 Cubans died from the virus; 1,232 of them were 60 years of age or older (71.5%). For this age group, the risk of dying is three and a half times higher than for the rest.

The pressures around the issue of population aging transcend the framework of medical care. One of the indicators that shows this is the so-called Dependency Ratio, which “expresses the weight that people of active age must bear as a consequence of those who are of inactive ages.” ONEI projections anticipate that until 2023 this statistic will show a favorable balance (of around two inactive people for three with work capacity). But from then on, a growing parable will begin that by the mid-2030s will virtually equalize both variables, making for more than 900 in need of some type of assistance per every 1,000 economically active Cubans.

“When that happens, what we perceive today as the needs of the population…will have largely disappeared, and will have been replaced by other demands,” reflects Professor Juan Carlos Albizu-Campos, from the Center for Cuban Economy Studies, in a July 2020 article.

His memory warns of the urgency of achieving “sustained economic growth,” to prevent a further decline in human development. During the period 2007-2017, our country fell 20 seats in that world ranking, to position 73. “The adoption of a vision in which the improvement of living conditions and the quality of survival occupy a place is central,” concludes Albizu-Campos.

However, there’s a long stretch between intentions and average reality. Julio Antonio confirms it every noon on the menus, which, despite the new prices and government statements, continue to show the little variety from before the Reorganization. “For the State, things should be more or less like in anyone’s house, doing the math so that the money can last,” Julio Antonio tries to understand. In recent weeks, he has been approached by more than one acquaintance to find out how to find a place in the dining room he attends.