In 2021, Cuba registered an infant mortality rate of 7.6 per 1,000 live births. This rate reversed the results below 5 achieved by the country for more than a decade. It also put an end to a downward trend maintained for more than twenty years. In 2022 the numbers are not encouraging. After the first 10 months of the year, the country registered a rate of 7.4. The information was offered by Dr. Tania Margarita Cruz, first deputy minister of the Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP), at the end of the first half of October. The results of this indicator in the last two years imply a rollback of almost three decades.

Looking back: the numbers

The most recent numbers are only comparable with those of 1996, when the island posted a slightly higher figure: 7.9. Since 2000, rates above 7 have not been quantified in Cuba.

The most elementary calculations show that the indicators for the previous year — and those reported until October of the current year — almost double the lowest figures reached just five years ago, in 2017, when this parameter set a historical record of 4.0. A record that, moreover, that was managed to be kept in 2018.

In terms of statistics, 2021 was the great turning point. However, the deterioration of good practices in maternal and child care in all the Cuban provinces began immediately after its historical records.

Before the arrival of the pandemic — pointed out by experts as the main cause of the increase in numbers — in 2019 the country rose to 5.0.

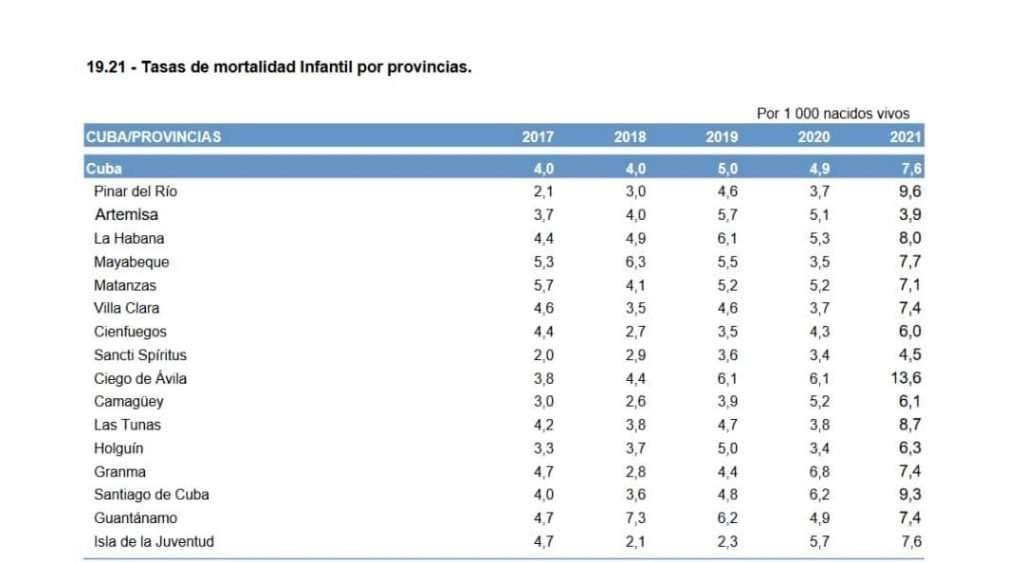

Evidence of this is the behavior of the parameter in provinces that in 2017 showed rates even lower than 4.0 — the country’s general average — such as Sancti Spíritus (2.0), Pinar del Río (2.1), Camagüey (3.0 ), Holguín (3.3) and Ciego de Ávila (3.8). In 2019 all these territories quantified higher numbers. Most of the rest of the country suffered the same fate.

*Caption:

19.21 – Infant mortality rates by province

CUBA/PROVINCES

Havana

Undoubtedly, the impact of the pandemic in 2021 radicalized the trend in the increase of infant mortality. The territories with the best statistics in 2017 illustrate this: Sancti Spíritus, Camagüey and Holguín doubled their statistics then, while Pinar del Río (9.6) and Ciego de Ávila (13.6) multiplied them almost four times.

Given the direct effects on the health of pregnant women and the context of tension in which the country’s health system was submerged, the efforts and resources were not sufficient to contain the growth in the figures. However, just two months before closing 2022, the island maintains a high indicator. This occurs despite the fact that Sars-Cov-2 has been contained with mass vaccination.

Cases and things of the upward trend

The fact that the rise in the Infant Mortality (IM) figures has not managed to change significantly so far in 2022 shows that the recovery of better numbers in the maternal infant health program (MIHP) depends on the solution of other causes not so new; some of them particularly aggravated.

This was verified in Dr. Tania Margarita Cruz’s most recent information when she pointed out among the main “problems related to the results of the program” that have been identified throughout the national territory this year, the “incomplete payrolls of cadres and officials involved in maternal and child care.

In the words of the deputy minister, this lack prevents the achievement of “the necessary effectiveness in the control and supervision actions that correspond to the cadres.” In particular, the systematic supervision and control actions of hygienic-sanitary conditions in hospital services. Without such control, “procedural violations are committed in some of the country’s institutions” which, according to Minister of Public Health José Ángel Portal Miranda, gives rise to the appearance of “acquired sepsis,” one of “the main causes of death” both infant and maternal.

At the end of October 2022, according to the deputy minister, “incomplete payrolls” were reported in Pinar del Río, Ciego de Ávila, Camagüey, Guantánamo, Santiago, Granma, Mayabeque, Villa Clara and Havana, nine of the country’s 15 provinces.

Nor does the constructive situation of the delivery and cesarean section rooms and other hospital structures help. The deterioration and overexploitation of health facilities, added to the lack of resources for their restoration, are factors that favor the appearance of infections acquired within medical centers. Thus, the forecasts are not promising. In the first six months of 2022, the execution of the budget in public health and social assistance was 16 times less than the investment, for example, in business services, real estate and rental activities (construction of infrastructure for tourism), according to data from the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI).

The execution of the budget allocated to public health and social assistance so far this year is equivalent to less than 2% of the country’s total investments.

In this way, in addition to the lack of personnel to control health procedures in accordance with those established, there is a lack of resources and money to improve infrastructure and facilitate compliance with protocols. Unfortunately, these are not the only shortcomings faced by MIHP.

According to a report by the newspaper Invasor, from the province of Ciego de Ávila — the territory with the highest mortality rate at the end of 2021 —, the causes range from the Family Doctor and Nurse’s Office, where sometimes pregnant women do not receive timely follow-up, to the maternity homes and the delivery and cesarean section rooms.

Dr. Luis Carmenate Martínez, a MIHP official and head of the Provincial Group of Gynecology and Obstetrics in said province, openly declared this to Invasor: “prenatal care, the evaluation of risks in pregnant women and the application of protocols has failed.”

Basically, according to the specialist, because in the healthcare areas there is a lack of “professionals in key positions,” there is a lack of “pediatricians in the Basic Work Groups” (BWG).

The BWGs are secondary healthcare teams made up of pediatricians, obstetricians, clinicians, psychologists and supervising nurses who must visit the offices at least once a month to consult and confirm or not the diagnoses of the family doctor on certain cases. In this sense, the BWGs perform vital work. But, when there is a lack of specialists at any of the levels of health care, “the rest begin to suffer,” as Dr. Carmenate Martínez defined it.

In the words of specialist doctor in Gerontology and Geriatrics Jesús Menéndez in the debate space Último Jueves of the magazine Temas: “the health system is a reflection of the country’s situation.” And Cuba is going through a crisis that began before the pandemic. Since then, the health system has faced, among other problems, according to Menéndez, “the economic one and the migration of personnel.”

Hospitals outside, society inside

Outside health institutions, other no less important factors have a negative impact on the infant mortality parameter.

As Dr. Francisco Fornaris Jiménez, first degree specialist in Pediatrics and head of the Provincial Department of MIHP in the province of Granma, acknowledged to the newspaper Demajagua, “the [high] rate of low weight at birth has been hitting us for 15 years…and the factors are multiple: social problems, the teenage pregnancy rate.”

Granma has been, in the last five years, the province of the country with the highest rate of teenage pregnancy, with 23.1% at the end of 2021, above the national average of 18%. But it is not the only one. Other provinces such as Camagüey, Las Tunas, and Holguín also exceed the national average, which is already high.

Risks such as low weight at birth and premature births are associated with teenage pregnancy on the island, and have been identified by the Cuban minister of health as among the main “causes of infant deaths.”

Teenage pregnancy in Cuban society has among its causes the early start of sexual relations and an insufficient comprehensive education of sexuality. It is also directly related to the concrete socioeconomic environment.

According to studies by Dr.C. Reina Fleites, professor at the Department of Sociology at the University of Havana, on the island early motherhood occurs more among mixed-race and black teenage girls, living in rural environments, unrelated to study and work, and in low-income households and in precarious conditions.

To aggravate these variables in the general scenario, since 2018 the lack of availability of contraceptive methods in the pharmacy network throughout the country has been added.

In essence, it is an inescapable fact that socioeconomic conditions affect the behavior of the infant mortality rate; not only because they can condition the occurrence of unintended pregnancies — whether early or not —, but also because they influence the quality of pregnancy. For this reason, mothers with lower income per capita, and those with poor housing conditions, are recognized as more worrying, said Dr. María Teresa Machín López-Portilla, head of MIHP in Pinar del Río, to the newspaper Guerrillero.

In Cuba, the successful confrontation of so many unfavorable variables requires an intersectoral work that today is recognized as non-existent and that is vital. If work in the community is not coordinated with primary and secondary health care, lowering the figures will take longer than it should. More time and, unfortunately, also more lives.