At a time of economic crisis and many uncertainties, a defiant “third wave” of a pandemic and an unjustifiable U.S. blockade from a democratic, human rights and international legality logic, there are many cross debates that promote dissimilar imaginations today in Cuba on the Cuban public sphere.

The discussion encompasses old and new themes: dialogue, the capacity and the limits of the political model; the rejection or the assumption of legacies of political thought to guide the destiny of the nation; how to manage the growing demands of various sectors of society; the place of the intellectual and the opportunity for critical discourses; the management and use of public information media; the independent press; foreign financing and interference in Cuban affairs; the media “lynching”; the scope and meaning of constitutional provisions (freedom of expression, freedom of movement, etc.); the rule of law, human rights, democracy, among many others.

None of these issues is lucky enough to be “Peacefully Gifted.” The presumed calm—as in the plot of Mikhail Sholokhov—is surrounded and peppered by dissimilar interpretations that fix or dispute the limits and legitimacies of the public sphere. The search for theoretical and ideological references have been staged, once again, in an open and frontal debate on the origins and particularities of “Cuban socialism,” on what the liberal, republican or social democratic idea has to say in this part of the world—and in this historical moment—, and because of the notion and scope of the “revolutionary,” about the “univocity” or plurality of the left. It is a discussion about power and being able to exist. There are no sterile ideas or naive positions: they all seek meaning, to construct or reaffirm political identities, to approach the “possible” or the “established,” the routes or the scenarios for emancipation.

At this moment, the struggle for words is a struggle for vindications, for their “original” or “derived” meaning and for how convenient it is to legitimize ideological and political positions in one sense or another. No symbolic or material field remains uncontested. But they are, at the same time, fragile spheres for manipulation, to distort in one sense or another the material content of each one of them, to conveniently massacre, and according to certain particular or collective agendas, behavioral or moral logics. All of this raises a political spectrum that asks again and again about the Cuban public sphere, its future, its possibilities, its disruptions and its ideological connections in a delicate moment of readjustment like the one it is experiencing.

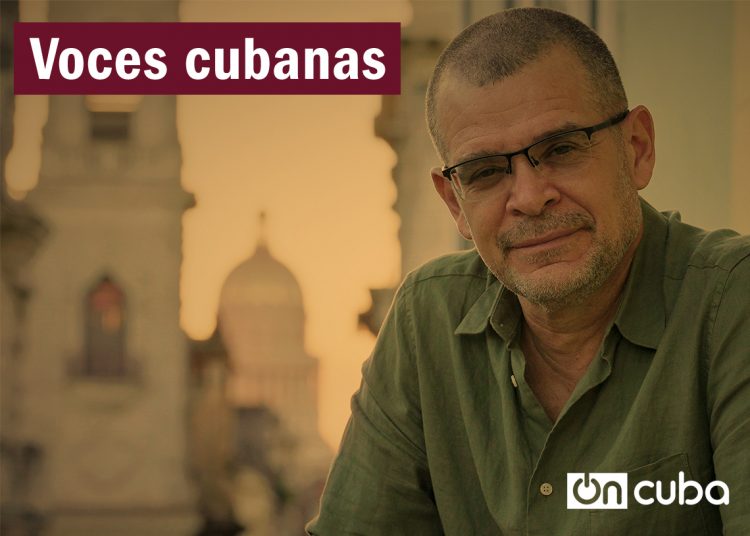

On some of these issues, we are premiering the series “Cuban Voices,” open to prominent Cuban intellectuals, with different views and backgrounds. The reader will notice an honest, sincere dialogue, without fanfare, which seeks to foster a necessary debate on issues that are related to the Cuban public sphere. That is the spirit of this series, which will feature in its first part an interview with film director Ernesto Daranas, and will continue in the coming weeks with several dossiers on these same questions.

For some time, Cuban society has been transformed socially and economically, and there are diverse kinds of demands by various sectors. Is the design of the Cuban State capable of absorbing and managing these demands?

I believe that the evidence is clear, there are hardly any systematic participation mechanisms, while the media, and the National Assembly itself, are governed by an agenda that is not always in tune with the most urgent problems of ordinary Cubans. This has been isolating the work of the State to the point that, in practice, it is the social networks that are channeling these demands.

Do you think that is what would be happening with the Task of Reorganization?

Exactly. It is not the same to do the math in the office of a ministry than it is on the table of a family that has started to eat only once a day. It is true that their children go to school and that if the grandfather gets sick he will be able to go to the doctor, the problem is that the very way in which they live conditions the health, education and real expectations of that family.

In different ways, the networks are expressing these contradictions, showing that a great deal of Cubans do not agree with the way in which the social pact of the Revolution is being reinterpreted after the lives of several generations have been governed by those rules of the game.

This is why they do not approve of the dollarization, nor do they accept the surname of “undue” for gratuities that they understand they have paid with their low income throughout their lives, nor does it seem to them that there is an acceptable relationship between the increase in salaries and the rise in prices of products and services.

In general, they question a calculation made on the basis of subsistence because they understand that it must be taken into account that we all need to dress, have a television and a refrigerator, go out with the family, have money in the mobile, fix the roof of the house, on Sundays have a beer, access to leisure, culture and those little things that are so important when it comes to talking about quality of life, even among low-income people.

What, then, has gone wrong, if you consider it that way, in these first months of the Task of Reorganization?

Remember that a few years ago the reform process was preceded by a broad popular consultation that was expressed, at least partially, in the Party Guidelines. However, the government now recognizes that most of these Guidelines have not been met. What is failing then is not only the absence of a more participatory model, but the ability of the State to effectively manage its own goals.

What do you think of the intensification of sanctions against Cuba that took place during the Trump administration in the midst of this crisis aggravated by the pandemic?

The blockade is unfair because it places the pressure that it is intended to exert on a government on the back of ordinary people, but it is also unfair that our social and economic model does not do everything necessary so that the talent and free initiative of this people constitute the great engine of our own development. Right now with the pandemic there is the paradox that while people are exposed to the virus by queuing, Cuban science works on various vaccine candidates. I do not know if there is another country in which these two extremes coexist. And you find this same talent that exists in science in almost any area of our social, political, cultural and economic life. That is then the only capital that Cuba has right now in its hands.

What to do then?

I am not an economist, but it is clear that a pound of pork at 100 pesos or a semi-empty agricultural market in a country full of marabú and surrounded by the sea cannot be explained only by the blockade. Our prosperity cannot be eternally at the expense of the current ally, the emigrant and tourist dollar, or the change of government in the United States. It is not possible that we have a Foreign Investment Law and that the business right of the Cuban to go as far as his capacity allows is not prioritized. There simply cannot be true independence without economic independence, and there is no future in sight if many of the country’s best talent and youth continue to migrate in search of the opportunities they should find in the nation that has formed them.

It is a dynamic that has an impact on the class composition (or of sectors, depending on the terminology assumed) of Cuban society and its dynamics of inequality….

The problem is not that there are more rich people; the problem is that there be fewer poor people. Anyway, those class interests that you mention already exist and are represented, among other figures, by a new class of entrepreneurs.

The current economic model favors the role of companies and military and civilian groups that administer several of our main economic sectors and a large part of the flow of foreign currency in the country, with different rules of the game from those of other state and private sectors that are crucial for the majority of the people.

This is what explains, for example, the imbalance of investment in sectors such as real estate and tourism with respect to others as sensitive as agriculture, fishing, housing or public health itself.

Such a design stops not only private initiative, but also the development of the socialist ownership and production models themselves. The consequence is a gigantic bureaucratic apparatus that encourages all kinds of irregularities.

There is no corruption better than another, and although the Newscast chooses to show us the fall of the so-called “kings of pigs, cheeses and onions,” the reality is that the design that corrupts is consolidated without hardly talking about it, with the aggravating circumstance that it is a model that makes Cuba a much easier target for sanctions.

There is no way around it then, without production and without a domestic market there can be no real economy, no exports, no effective Task of Reorganization, nor can we aspire to a better country for ordinary Cubans and, by derivation, attractive to foreign investment. And it is not true that it is necessary renounce socialism for that, because it is the laws and the rules of the game of a society that determine how the wealth that is generated is reverted to rights and social justice. What happens is that these rules have to be clear and be the same for everyone.

In such a complex economic and social context, what do you think would be the role of the intellectual in Cuba today? Is there a need for critical discourses in our society?

At this point, dialogues are much more necessary than discourses, but it must be a dialogue for everyone, not just for intellectuals. The problem now is the queues, the productive paralysis, the falling roofs, the danger of this food crisis getting worse, the hospitals without antibiotics, corruption, bureaucracy, the pandemic, the exodus of young people and professionals, the blockade , the crack of social inequality, the new monetary duality, the inflation that scarcity and the dollar itself generate, the number of people whose new wages cannot cover their most basic needs for subsistence, that other large number of citizens who have not received an income increase, the need for a true economic opening and respect for basic freedoms. It is about improving this country and giving us back a life project with a notion of the future. Intellectuals are not the center of the universe, but we have an obvious responsibility in this regard.

Today there is a great debate about the foreign financing of projects aimed at subversion in Cuba. How is this phenomenon in the Cuban political, economic and social context understood? Can they be delimited in this field to sectors, groups, media?

I believe that any attempt by a state to directly subvert the order of another state is questionable, and I say this regardless of in what sense that interference takes place. Outside of that, anyone’s right to be financed is clear. In fact, the State exercises it by looking for investments and, in the case of remittances, it does not stop to filter who sends them. What would be healthy is that, as is the case elsewhere, this information was public, or at least open to consultation, regardless of whether it is state or private actors.

It would seem that the journalistic discourse has substituted, to some extent, the legal processes to judge, provide evidence, and presume innocence, in the case of accusations of links between individuals or entities with subversion projects and “regime change” against Cuba. What is your opinion on this problem?

Journalism is not done with diatribes. If you tell me that there is someone paid by the United States government, then it is up to you to offer me concrete evidence and allow that person to express their point of view, only then can I also exercise my right to know it. That is journalism. Other than that, disagreeing with what one considers to be wrong in one’s country does not make any Cuban an annexationist, agent of the empire or the author of some “soft coup.” In fact, I know several of the young people from 27N and I know that they are nothing of the kind. The writings of several of them, and of some of their parents, reflect a maturity that has penetrated even many revolutionaries who understand that there is no right to slander, besiege, deprive of their work, imprison, attack or denigrate anyone who expresses himself or demonstrate peacefully.

The thought or desire for change of any Cuban cannot be criminalized. But that is not only happening now, under the stress of a moment as complex as this, but it has been a trend responsible for several of the darkest episodes of the Revolution, damaging the lives of many honest people, and affecting even those who exercise their right to express their idea of what Cuban socialism can and should be. What happens with all this is that we have reached the point where more and more people no longer see their enemy being stoned and that indicates that everyone is losing something with the transfer of acts of repudiation to the media. It cannot be overlooked that Cubans from the island have already seen how those same Cubans who were asked yesterday to throw a carton of eggs at return as saviors. Manipulation, obviously, is losing its effectiveness, which does not make it less unfair, dangerous and reprehensible.

What do you think are the most complex challenges for Cuban socialism at this time?

To name just three: dogmatism, corruption and poverty. The first two slow down the renewal it needs and the third is, in no small measure, a consequence of them.

Another Party Congress is coming, what do you expect from it?

I do not expect anything that does not come from ourselves and our willingness to accept the right of the other to think and act differently. I do not believe that absolute unanimity is possible between honest men and women, and without honesty there can be no authentic consensus. Any Cuban knows that the true vanguard is in the people and that the main thing about a leader is not the formalities of his militancy, but his ability and interest in connecting with the real needs of the people. That is why it is so important that these leaders can be directly elected by the people to whom they are owed. There is no better way to tune the government’s management with our true urgencies.

Finally, what do you think are the limits of legitimacy in citizen action in Cuba?

They should be what the Constitution establishes. That is why it is clear that peaceful citizen action is always legitimate, and based on this we must continue to insist on the possibility of a permanent real dialogue. Although it seems that it does not make sense, that dialogue is the only true opportunity that each of the parties has, at least I cannot conceive of another way that a “new normal” begins to be possible among us.

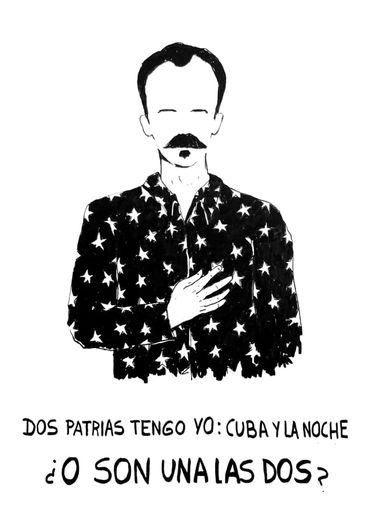

In Martí there is an excellent reference to start this process and his legacy contains everything that Cuba needs at this time. By the way, if you are going to use any image that accompanies this interview, I would love for it to be the Martí that Carolina Barrero has illustrated.

I enjoyed reading this commentary. I’m a 75 yr old woman, painter, reflective human. I grew up in Miami from 1950 to 1963. Outside of my parents visiting Cuba for a vacation, an immigrant boyfriend in high school, & a husband who was deployed as a Marine by Kennedy, I know pitifully nothing. I’ve read some books & even visited Cuba in 2019. I applaud your call for dialogue with people. Citizens of Cuba certainly need to voice their needs & goals for their country. Hopefully we can share in this dialog with citizens of the US. Personally, my heart aches that Cubans in the US can’t freely visit family & Cubans can’t come here. I know there is some loosening of travel, but it remains unsatisfying. That food & other health & welfare for poor in both of our countries is deplorable. Now the virus has added another deadly problem. I would be open for a public platform where these issues could be discussed. Thank you.