Saúl Berenthal is a persevering man. Nothing seems to destroy his will to commercially establish his company in Cuba, where he was born.

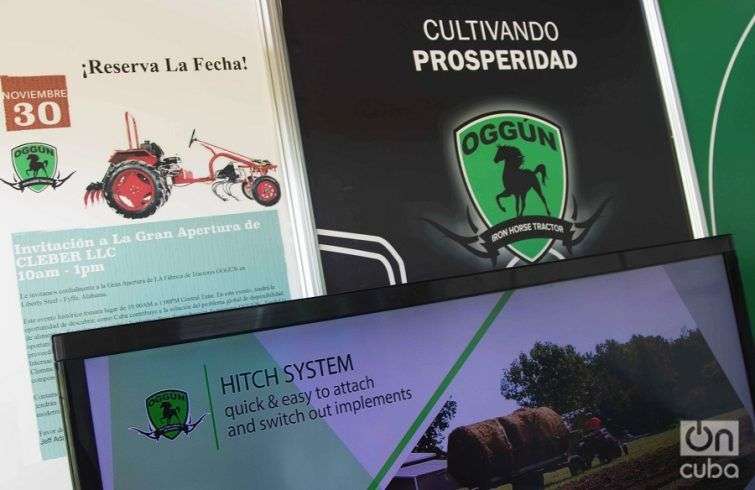

Berenthal, who emigrated in 1960, is one of the founders of Cleber LLC, a company based in Alabama trying to introduce on the island a small-size tractor model named Oggún, like the warrior deity of the Yoruba mythology.

An exhibitor in Cuban commercial marketplaces, like the Havana International Trade Fair and the International Agribusiness-Food Fair, Cleber LLC presented an application to manufacture its tractors in the Mariel Special Zone, which was initially well accepted. Their persistence to establish their business in Cuba made them deserving of illustrative headlines that highlighted their role as a standard bearer against the U.S. blockade.

However, after they got the necessary U.S. government licenses in February, their project in Mariel has been suspended by the Cuban authorities. The international media echoed this, underlining the lack of reasons for that decision and its possible connotations for bilateral relations.

Even so, Cleber LLC was present in FIHAV 2016 and OnCuba went to meet Saúl Berenthal to find out, from his perspective, the interiorities and implications of what happened.

“This is not something that happened a few days ago,” Berenthal commented. “We already had some indications that it could happen. That’s why, without giving up hope that it would be approved in Cuba, we decided to also set up the project in Alabama. Today we have there a factory very similar to the one we would have wanted to set up in Mariel, which is already manufacturing tractors,” he said.

“Part of what we had planned was to also bring those tractors to Cuba to be able to certify them through the necessary tests. This idea was stopped and then what we did was take the first seven tractors to try them out in the large U.S. agricultural universities in different parts of the country to test the tractor in different types of soils, climate, in different crops, to find out about any possible problems the tractor could have and thus de able to modify it subsequently for the benefit of the clients. That is to say, in situ quality control, something that seemed very important for us for a tractor thought-out to be used in Cuba in different places and different conditions,” he specifies.

“And although we understood what could happen in Mariel, we decided to come to FIHAV prepared beforehand, with a greater range of products and knowing that we have to take another course to carry out our project of the Oggún tractors in Cuba,” Berenthal said to OnCuba.

What reasons were you given about the exclusion of your project from Mariel?

Well, they gave us three principal reasons. First, that our company does not have a long record in the manufacturing of tractors, which is true because we are a relatively new company, of entrepreneurs who decided to make a tractor that had already been designed decades ago in the United States, and to start it up with updated logics in response to Cuba’s specific needs.

We don’t have a wide range of products in that direction, as the Chinese or Russian or other U.S. manufacturers do, but we do have a tractor designed for the Cuban agricultural environment and for us that is a strong point. But it’s true that we do not have a big record as a company.

The second reason was that we did not have the technologies and the environmental protection devices, and the third was the same but referring to the operator’s safety. But that is something we are incorporating based on the tests carried out in the U.S. universities. We knew they were changes that had to be made and in our plan they were part of the necessary process of verification and modification for the certification here. But they took into account the conditions of the initial project, which did not specifically correspond to what was regulated in Cuba and therefore they considered it a defect.

However, the Mariel officials with whom we met, and who were very pleasant and professional when explaining this, told us that that decision did not close Cuba’s doors to us and that there were other opportunities to do business on the island. And we, for our part, informed them of our intention to continue trying to do it, speaking with the Ministry of Agriculture, with the Ministry of Construction, to propose to them the same project but outside Mariel, with a focus according to the new possibilities, which seemed like a good idea to them.

Then you don’t feel discouraged with what happened?

Absolutely not. I’m going to tell you something that I have affirmed other times: I came to Cuba with the intention of being able to contribute in what I can and to be able to participate in what they let me. Therefore our company will continue trying to bring what it can and to analyze the different environments in which we are allowed to participate. We don’t want to give up.

To continue forward we had to get licenses to be able to work with the Cuban government, and that was something difficult, but we were able to convince the U.S. authorities that we should have that option, with the state agriculture as well as construction entities. And a few weeks ago we were able to get the U.S. government to give us four specific licenses, not just to sell our tractor on the island but also to bring tools and supplies and be able to do the same for the construction sector, which is another area in which we would like to contribute.

That’s why we came to FIHAV prepared to expand the business talks in these directions and we have already made some contacts to certify the tractors and be able to import them to Cuba, as well as the supplies and necessary parts for their functioning.

What is your assessment of your company’s exclusion from the Mariel Special Zone, in light of the current moment in diplomatic and commercial relations between the two countries? Do you think it is a momentary case or do you see in this certain distrust in U.S. investment in general, as some international media have opined?

One can never be sure about the actions of persons or governments, but I particularly believe the Mariel officials who explained to us our exclusion. Mariel is a zone specifically thought for certain business and technological levels, and I understand and accept the reasons they gave us, especially our short record in the manufacturing of tractors.

But I also understand that in Cuba there is a need for what we are proposing. And the fact that they presented us with others roads we can take with our project and that we also have the backing of the U.S. authorities to continue attempting it seems important to me.

I personally don’t think that Mariel has decided to close its doors to U.S. projects. That doesn’t seem to be their intention. What I do know is that it is very difficult for U.S. businesspeople to do things given a series of questions that involve the embargo.

We have had to work very hard to get those licenses from our government. Just imagine other U.S. companies that will have to go through the same situations. And more so the big companies, which have very rigorous legal offices and that tend to be more respectful of what has been established to not brake the existing laws.

Several of those companies are working with ours to be able to provide their products in Cuba, not directly but through us. They do the same in other Latin American and Caribbean countries, using distributors and representatives, and some of them came to FIHAV to see how we could promote their products in the Cuban market. That is a way for U.S. companies to be able to start establishing their trademark and reputation in Cuba without having to do it directly or taking the risk of violating the embargo.

Do you then think that the blockade continues being, despite the Obama administration’s measures, the key point for the normalization of relations between the two countries….

That’s right. I was recently asked why the U.S. companies view the risk as one of the reasons to not do business in Cuba. And in my opinion it is something they assume themselves for fear of the embargo. The embargo is what creates the risk and that’s why it is a constraint.

By from what I have been able to see in the Fair, the big companies from other countries are coming to the island, they are establishing commercial relations and the embargo at this point serves more to isolate the United States than to isolate Cuba. And it is somewhat depressing that we U.S. businesspeople are the only ones who are being isolated from doing business with this country.

What do you think could happen in the immediate future, taking into account that your country is just a few days away from the elections?

I am not a fortune-teller nor do I get mixed up in politics, but in my opinion, independently of who will govern, sooner or later, faster or slower, the embargo will be eliminated. There’s no reason for it to continue because it damages more the U.S. companies than the Cubans or those of the other countries. The latter are able to enjoy trading with them, while in the United States there is still respect, or fear, regarding doing business in Cuba. Thus the embargo has to be lifted at some time, I hope soon, and I want to be here when that happens.

TN: Berenthal’s statements were translated from the Spanish.