Enrique Pineda Barnet died this Monday at the age of 87. Following his passing, I read on a friend’s Facebook profile that Barnet was an island within an island. The phrase has not been out of my head. I think that definition faithfully portrayed a part of the filmmaker’s life and that particular cinematographic look at Cuba that he never lost, as he never lost the joy of being part of the miracle of life and of cinematographic creation.

Enrique was a precocious child before becoming a great filmmaker. He was born in 1933 and when he was only five years old, he played the character of the black in the Cuban vernacular theater. Years later he made his first foray as a radio actor.

Those first experiences formed the multifaceted personality of a young man who over time became a Renaissance man in Cuban culture. He ventured into journalism, literature (he won the Alfonso Hernández Cata National Prize for Literature in 1953 for his short story “Y más allá la brisa”), locution, he was one of the founders of the influential Nuestra Tiempo Cultural Society and one of the first volunteer teachers to climb the Sierra Maestra. In his journalistic work, he showed deep acuteness and excellent narrative ability, attributes with which he established himself since early on in Cuban journalism.

In cinema he found the definitive space to guide that fervor for creation that defined the master lines of his future work. He entered the Cuban Institute of Cinema Arts and Industry at the beginning of the 1960s and in 1963 he premiered the work Giselle, with which he surprised even the most seasoned by his extreme sensitivity, his ability to be aware of even the smallest detail and, above all, by anticipating his time. Viewing again this film today, one will be able to realize that it summarizes contemporary visions on all four sides.

Barnet’s biography is from a movie. I don’t know exactly why (but perhaps I can guess) both his life and part of his work are not fully known by the Cuban public. He has been relegated to the cloister of specialists.

His work as a scriptwriter in Soy Cuba, that ambitious and surprising co-production between Cuba and the former Soviet Union, appears as a primary mark in the obligatory reference career in Latin American cinema, which, although after its premiere in 1964 did not awaken the best applause from a segment of specialized critics of the time, was recognized decades later as a classic in film history.

Pineda Barnet himself, a demanding filmmaker, was not satisfied either with the final result of the work or with the belated accolades. But those who knew him closely know that it was not easy to discover him in excessive exaltation or conformism. He even took some distance from those from whom he only heard menial flattery or praise where he expected questioning or criticism. That is why he also found an oasis of happiness and hope when some creative approaches were suggested or questioned during the process of making some of his films.

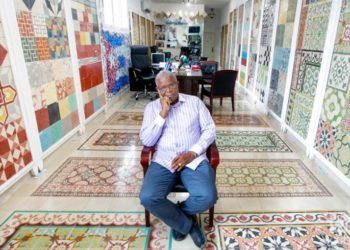

He was a mirror of suspicions. He easily found the backdrops that animated any discussion, controversy or idea and from there he decided whether to install himself in the particular geometry of said project or observation. His gaze said it all. He scrutinized thoroughly with eyes that did not lose the amazement of life and he never neglected the elegant man bearing for which many recognized him, along with, of course, the magnitude of his work.

His name refers directly to La Bella del Alhambra, that classic of Cuban cinema that is enjoyed like the first day. Certainly, the island’s cinematographic sphere has not been lavish in this type of work, but the proven quality of the film put it to compete in the best cinematographic championships on the continent.

The film, it is known, was surrounded by controversy both before its premiere and after its public screening at the Yara movie theater in 1989. Based on the literary sources of “Canción de Rachel,” by Miguel Barnet (who also joined in the scriptwriting), its protagonist, Beatriz Valdés, played a masterful role. The film caused a sensation among the public, won the favor of the critics, and started marking an era and a new territory of creation in Cuban cinema. Beatriz, in the role of the stunning showgirl, acquired the status of symbol and legend among Cubans.

Despite these profuse credentials, the film was not sufficiently considered at the Havana Latin American Film Festival, where it competed and everyone expected it to win the highest awards, including, of course, that for best actress. However, Beatriz, who served as presenter at the award ceremony of the prestigious event, saw how the award was awarded to an Argentine actress. After that first stumble with disappointment, Barnet and Beatriz herself agreed that the best award had already been obtained from the Cuban public.

It is known that, after the death of a prominent artist or any other personality, many perhaps without the necessary knowledge or guided by the always ready hands of opportunism, praise his work or put it as an example of the creation of a country, ignoring the details of lives that at times they could have done more with greater support or simply with others’ understanding.

Barnet, the author of other imponderable works such as Mella, was also one of those filmmakers who lived through his moments of silence and whose creative impulses were not fully understood at various times in Cuban culture. He himself recognized that he once felt that they tried to obviate his name from Cuban cinema. But save for those wrongs that, on the other hand, often define the personality, Barnet was already a complete filmmaker, an artist very loved by his colleagues, friends and by the followers of his work, who never stopped being interested in his creative paths and his health.

His death closes an era for Cuban cinema and, at the same time, opens a historical dimension in which many young filmmakers can recognize themselves and have the certainty, as Barnet had, that their destiny is to overcome the obstacles imposed and the misunderstandings, to always find the light at the end of the tunnel of Cuban cinema.