When Dr. Mitchell Valdés-Sosa, one of the directors of the Cuban Neuroscience Center (CNEURO), is asked about the so-called “Havana Syndrome,” he replies without hesitation that he doesn’t believe it exists.

“We believe that there really is no ‘Havana Syndrome’. What we think is that there are people who got sick from different causes and that we must continue the investigations to verify this or any other hypothesis,” he said about the health incidents reported by North American diplomats in the Cuban capital, which have been the source of the most diverse theories and speculations.

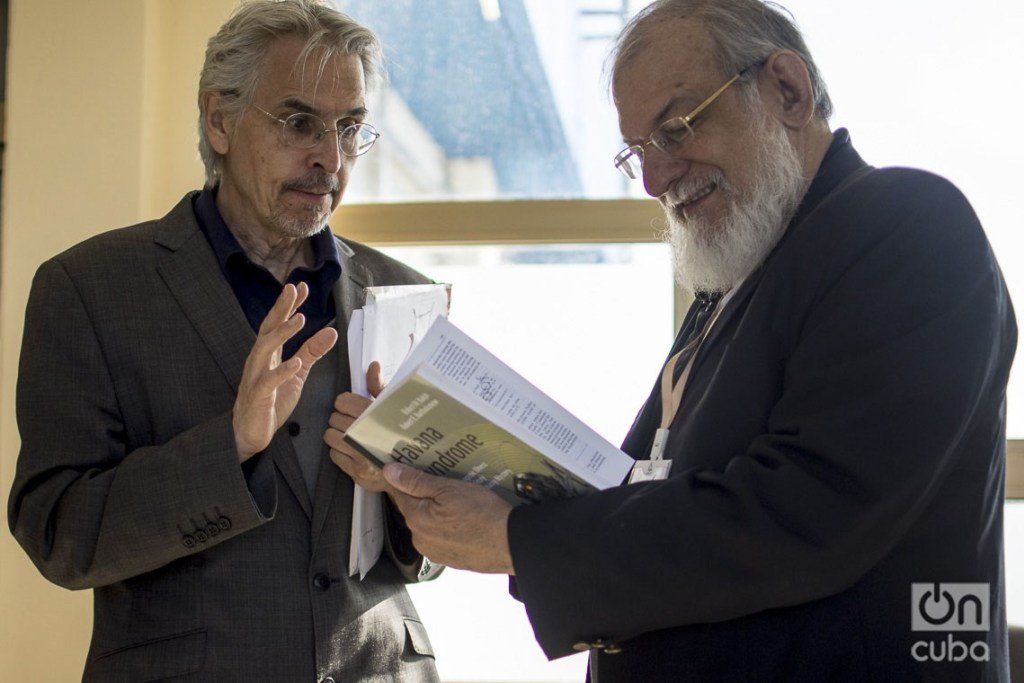

Several of these hypotheses were the subject of analysis this week at the CNEURO, during the holding of the Is There a Havana’s Syndrome? lthe holding of the Is There a Havana Syndrome?” event, which, according to Valdés-Sosa, sought to promote an “open and frank” debate about what happened. For this, the debates were attended by researchers and academics from several countries, including Cuba, United States and Canada, the main countries involved in this plot with hues of mystery and with an unquestionable political repercussion.

After the first U.S. reports in Havana, three years ago, the Trump administration―wanting to dismantle the “thaw” promoted by Barack Obama―did not hesitate to claim that its diplomats were targeted. And, although he did not directly blame Cuba, he did blame it for not adequately protecting its officials and ended up drastically reducing its diplomatic presence on the island and transferring consular procedures for Cubans to third countries, among other measures.

The reports of U.S. diplomats would be followed by those of Canada, which also suspended most of its consular services in Cuba, but did not focus on what happened from a political nuance and assumed a more collaborative stance with Cuban authorities and researchers than that of its U.S. neighbors.

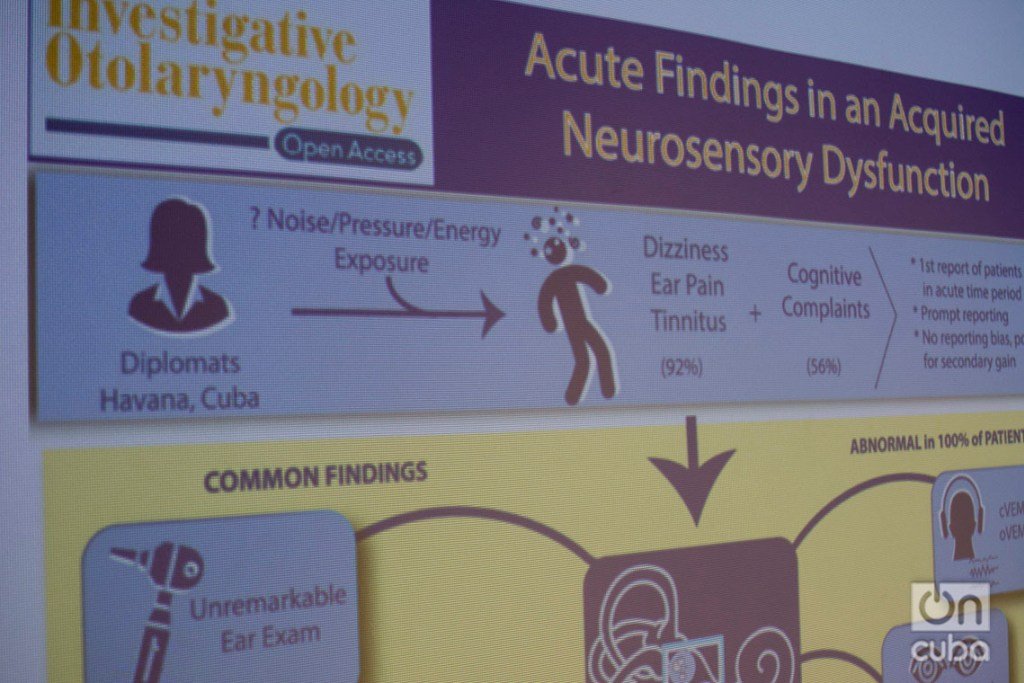

In total, about 40 U.S. and Canadian diplomats working in Havana reported affectations related to the mysterious “syndrome,” whose symptoms include dizziness, nausea, hearing loss, low concentration, blurred vision, memory loss and other neurological problems.

The case has aroused many passions and questions, and has motivated numerous journalistic and scientific articles―some of them criticized by other researchers, even now in the Havana event, such as the one published by doctors from the University of Pennsylvania in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA)―but the cause of the incidents remains unknown.

Sonic attacks? Neurotoxins?

The first theory that was publicly handled, which gained rapid media relevance without having been proven by science, was that of alleged sonic attacks. The hearing conditions reported weighed more on the balance than other symptoms, to the point that today, many months later, these health incidents continue to be called that way by some people and the media, even though the researchers have already rejected that first hypothesis.

“The idea of an attack is absurd and there is no scientific evidence to support it,” says Valdés-Sosa, a position consistently repeated by researchers and the Cuban government in the face of accusations by the State Department.

Cuba: no hay evidencia científica de “ataques” a diplomáticos norteamericanos

“That someone has been persecuting diplomats throughout Havana with mysterious rays or an unknown sound equipment, as was said at the beginning, violates the laws of science; it’s science fiction. Nor is there evidence of damage by these supposed sounds in the white matter of the brain, because the causes of these reports can be many, even prior to the incidents. However, both things were given great importance in the press at the time,” says the director of CNEURO.

“We also believe that if the U.S. government repeated tells the diplomats that they are under attack, it gives them stress and acts as an amplifier of any symptoms,” he adds. “It doesn’t mean that they cannot be sick, but the existence of a theory like that of the sonic weapon, repeated even without bases, can confuse people more than help them, and hinder the way they interpret their condition.”

Even so, this hypothesis marked the course of the initial studies, including those of Cuba’s own inquiry commission.

“Initially the problem of hearing loss was important and that is why we focused on that, but now it has been shown that really no diplomat has acquired hearing losses while in Cuba, and that, in those who had them, they were preexisting. Then, as the hypotheses on the case have changed, we have varied the course of our studies to see what we can find,” he explains.

And the current course, at least for Cubans and Canadians―allied in an investigation into strange conditions―points to the possible effect of pesticides used in Cuba in the frequent spraying of mosquitoes that transmit diseases such as dengue and Zika.

“We are now conducting an investigation with Canadian scientists, led by Professor Alon Friedman of the Dalhousie University of Halifax, now participating in our event, and with the collaboration of the Canadian government, whose hypothesis is that diplomats were affected by neurotoxins, by the fumigation against mosquitos,” confirms Valdés-Sosa.

It is, he says, the “most serious approach to a joint study” in which Cubans are currently working, which has led them to investigate groups of people exposed to pesticides on the island. However, it is still an investigation in progress, without conclusions, and with a margin of uncertainty until there are reliable results.

“There are reports that chronic exposure to pesticides can cause neurological damage. It isn’t that we are sure that this is the answer in this case, but we are open to examine the hypothesis,” he says.

Evidences, media, politics

To arrive at the truth, an idea repeated several times these days during the event held at the CNEURO, the main thing is to maintain a firm grasp of the existing evidence and data, and discard everything that may be conditioned―or rather distorted―from the prism of politics and the media.

This was emphasized by several speakers such as professors Sergio Della Sala, from the University of Edinburgh (Scotland); Robert Bartholomew of the University of Auckland (New Zealand) ―who manages the hypothesis of stress or collective hysteria―and the Cuban Pedro Valdés-Sosa, of the CNEURO; as well as Mark Cohen of the University of Los Angeles, for whom the use or not of the word “syndrome” is not the most important thing.

“Calling these conditions a syndrome is not particularly significant,” says Cohen. “The main thing is that there is a group of reports of people who sincerely suffer. I believe that the affected officials are not faking the symptoms and that their conditions are real. The cause of these symptoms is something else, and that is what we must discover, because these incidents have become a matter of international diplomacy and a challenge for the scientific community worldwide.”

The American professor, a neuroscientist specializing in the development of high-tech instruments, hopes that science can finally understand these disorders “well enough so that those affected can be treated in the best way” and, like his Cuban colleague Mitchell Valdés-Sosa, he does not support the theory of “acoustic attacks.”

“My work considers the question of what kind of physical damage can be caused to brain tissue by sound waves and the amount that would be needed to alter brain activity to the point of causing severe damage, and it is extremely difficult for me to imagine a device that remotely and through concrete walls and blocks can cause similar damage, specifically focused on certain individuals,” he says.

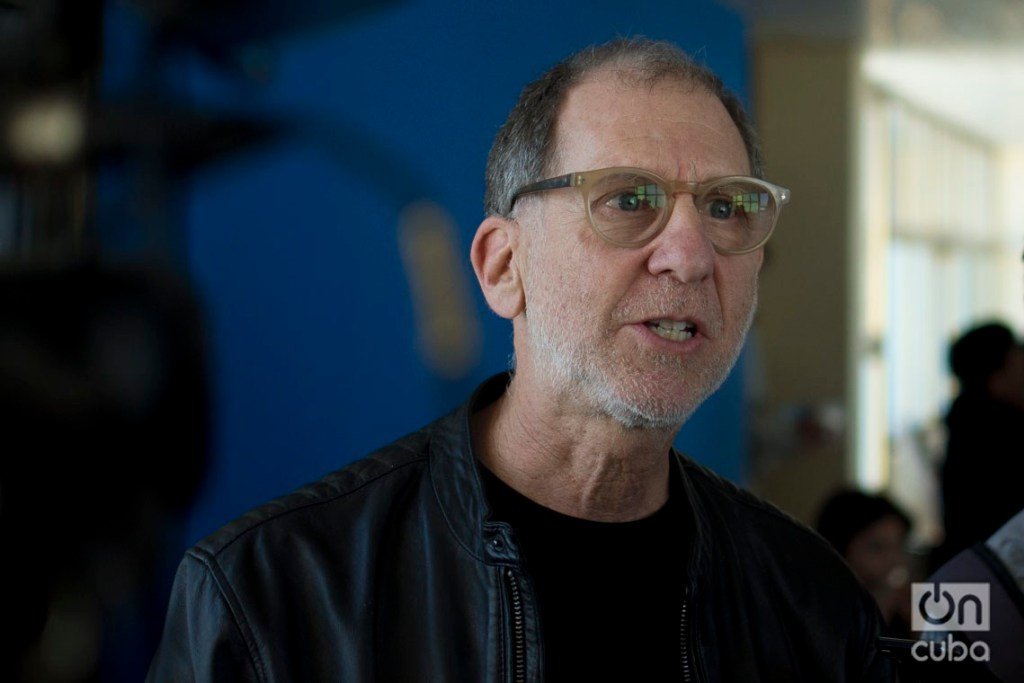

For his part, American Mark Rasenik, from the University of Illinois (United States) and member of the Academy of Sciences of Cuba, believes that the term “Havana Syndrome” is not based on science but that it is a media invention.

“We scientists did not coin the ‘Havana Syndrome’, it was the press. I have never called it that. However, what we cannot ignore is that something happened to these people and it is up to us to find out what it is. That is our responsibility as scientists,” he says.

However, Rasenik insists on the need for an “impartial” look at what happened, and to avoid government constraints and interference.

“Everything involving this case should transcend politics. The idea of knowing the truth and guaranteeing the security of diplomats must be what’s most important and cannot be influenced by the interests of a government or power group,” he insists. “In the case of the United States, it is true that the State Department has not explicitly blamed the Cubans, but at the same time has refused to share information and has taken a group of measures without a clear scientific support that have affected bilateral relations and, in particular, the people of both countries.”

Even so, the professor of physiology and psychiatry thinks that it is possible to surpass this episode and recover the links that were beginning to strengthen between the two countries when the mysterious incidents came to light.

“I sincerely hope that, with the necessary will and the contribution of scientists, we can resolve this situation and, as a result, Cubans can again process their visas in Cuba and that we can restore a relationship that had begun to normalize during the Obama administration,” he argued.

A joint look

After two days of intense debates at the CNEURO, the origin of the so-called “Havana Syndrome” is still far from being revealed. There are, of course, clues to follow and hypothesis to check, while others have been left behind. But in what both the Cuban and foreign scientists attending the event seem to agree on is the need to share the information and results obtained, to work together from a multidisciplinary approach.

This is the opinion of Luis Velázquez, neurologist, neurophysiologist and president of the Academy of Sciences of Cuba, for whom the recently concluded event has been very enriching in order to increasingly come closer to more precise conclusions and “put an end to a situation as unfortunate as this one.” For this, he says, effective international collaboration is important.

“In 2018 we published a global call to the Academies and scientists of the world to analyze these cases, because there are problems that undoubtedly require a multidisciplinary participation to get to the truth,” he says and explains that he made the call through the magazine Medic Review.

This call, he says, is still open today, and remains in full force because of the impact these incidents have had from different angles.

“If we see them from the point of view of science, there is the fact that, after three years of hypotheses and research, it still represents a challenge for scientists, a field still under exploration and a source of doubt even about publications that have come out on the subject,” Velázquez affirms. “But, on the other hand, there is an ethical component that must be taken into account, because scientists have a commitment not only with our countries and governments but in the universal order, a commitment that involves transmitting knowledge and contributing with it to the wellbeing of people.”

“This is very important for Cuba, first of all because of the relevance of people’s health and safety, in this case diplomats, and because these incidents have been used to accuse our country and damage our international relations, particularly with the United States. That is why we aspire to finally discover what happened and to collaborate with researchers who are sincerely interested in it,” he added.

Meanwhile, Mitchell Valdés-Sosa regrets that he has not been able to establish an exchange “on a more formal level” with the United States Academy of Sciences and the institutions of that country that have directly investigated the affected officials, but appreciates the attitude and collaboration of some scientists who “have been willing to talk with us and present their views.”

The director of the CNEURO advances that, along with his work with the team of researchers from Canada with which they are tracing possible neurotoxin effects, “in the coming months we will continue to insist on the need for a dialogue,” not only with the American institutions and researchers, but with the entire international scientific community.

“In science, it is necessary to debate in a serious and open way about the evidence and existing results, and the holding of events like this demonstrates that dialogue is what can really clarify what happened with the North American diplomats in Havana,” he concludes. “Investigate and debate, that must be the path to follow to reach the truth.”