Thirty-six was his number as a recruit in UMAP. Jaime Ortega spent eight months there after returning from his theological studies in Montreal and beginning his life as a priest in Matanzas, his hometown. He refused to bear resentment and hatred toward that injustice, for which the revolutionary government was responsible. Jaime Ortega reemerged by reaffirming his faith and decision to serve the reconciliation of Cubans.

Among the many anecdotes that he repeated in his office I remember a very special one. Jaime told how at UMAP he had become friends with the other recruits, helping them to communicate with their family, giving spiritual support to those to whom he could, something that allowed him to understand his destiny there as a divine mission. He always emphasized the role that individual will and temperament play in defining circumstances. One thing is what the context imposes and another is how everyone processes it, if they decide not to stop being who they are.

In UMAP and later, Jaime Ortega was what he decided to be since he was nineteen: a priest. “I am myself and my circumstance,” he liked to repeat that famous phrase of Ortega y Gasset, to then clarify it; it never implied for the future Cuban cardinal the determinism of being only circumstance. Of course, the Cuban understood the importance of the context, but underlined the human will of the being according to his knowledge and moral sense. Ortega, the priest, read and understood the Spanish philosopher. “I am myself and my circumstance,” and added: “And if I don’t save it, I don’t save myself.”

Months after arriving in UMAP, the political commissar of the military unit, of whom Jaime said his name was not important, was bothered when he noticed that his comrades called him “father” and ordered that they call him by his name or simply “thirty-six,” his number. The result of that clash was a lesson. Jaime had planted his seed in his people, his comrades, and they kept calling him what priests are called, “father.” The officers found out, but they understood that, under their noses, without anger, the “father” had created a natural link among these men. It was less difficult to accept it than to fight against it.

Speaking of our respective religions, in which he supported the efforts of interreligious dialogue launched towards Judaism by his admired John Paul II, Cardinal Ortega stressed that “one of the greatest forces of good versus error is constancy.” His rise in the Catholic Church and his prominent role in Cuban society and in Church-State relations for decades can be understood from that perspective.

Jaime Ortega knew what he was: a Catholic priest. He lived based on that persistent condition, and enjoyed each of his small victories, which, as a whole, became great. Not in vain later on his bishop’s slogan would be: “My grace is enough for you,” taken from Saint Paul’s second letter to the Corinthians. Rather than worrying about marking rhetorical points, he changed circumstances.

The conditions of the Cuban religious communities in which Ortega began his priesthood and rise in the Catholic hierarchy were difficult. The Cuban Catholic leaders around Cardinal Arteaga, following the dictates of his parishioners, and the visions of their main economic, political and intellectual supports clashed with a popular and authentic revolution in the early 1960s. From that conflict, they and the institution came out looking badly.

By 1964, when Ortega returns to Cuba, the Church’s conflict with the Revolution had put the former in a precarious situation. A large part of the greater economic support of the ecclesiastic and social activity of the Church had emigrated while the temples were identified as counterrevolutionary spaces, and the Catholic educational network dismantled with the nationalization of its schools. Atheism―a so-called scientific one―was a state policy, while religion was considered “the opium of the people” and a “remnant of the old society destined to disappear.”

After touching rock bottom, with the advantage of the renewal of the Second Vatican Council, committing to be the Church (community, assembly, place of prayer) of the people who remained on the island, a new batch of Catholic leaders began recovering. (By the way, differently but with important similarities, that process of adaptation, work, and national deep-rooting occurred in other religious communities such as the historic Protestantism and the Jewish community.) It was a non-heroic resistance, based on the new realities of the country. Ortega and others, gathered around different bishops throughout the island, gradually recovered the spaces, without demanding anything that they had not already achieved within society.

The priestly work of Jaime Ortega in those decisive years for the Church sowed the vision and gradualist methodology from which his leadership would emerge nationally and internationally. He served in Matanzas, covering various territories of the city and surrounding areas; in Pinar del Río, promoted to bishop, where he was during the difficult situation of Mariel’s exodus and the harassment that accompanied those who left, and in Havana, where he acted as president of the Conference of Bishops and was promoted to cardinal.

The miracle of recovering the space of religion in Cuban society was not a matter of one day, but of long work, persistently organized and exhibiting an admirable awareness of the importance of time and sequence in politics.

First, order was put in the temples, avoiding the politicization of religious activity, acting as a space of convergence in the faith of the Cubans, whatever their political differences, without exclusions. Then in the social field, the Church sought to give hope and legitimate space for mercy and dialogue, as a haven of peace in the face of the overflow of the partisan characteristic of totalitarian mobilization and its oppositions. Parallel to this, new publications came out, new library and educational networks were rebuilt. To the extent that society opened new dynamics and institutional capacity allowed it, so did the Church’s work. Internationally, there was a work in tandem with the Vatican diplomacy that had in nuncio Cezare Zachi a channel for promoting rapprochement between the bishops and the government, particularly the primary figure that was Fidel Castro in Cuban politics. Since then, sincere dialogues emerged with important criticisms but also clear statements from bishops and calls to their counterparts in the U.S. against the hostile policy of the U.S. government against Cuba.

By the beginning of the 1980s, atheism, a feature of Cuban totalitarian politics, was already in retreat. Religious weddings and baptisms, as well as attendance to the temples reached the levels of 1964-65, in a frank sign of recovery. With a kind of political judo, grappling with the revolutionary government on its own ground and from its greatest strength, nationalism, religious communities, in the first place the Catholic Church under leaders like Ortega (not acting alone but in line with others that accompanied him), enabled not only their own recovery but a new dynamic in Church-civil society-State relations.

By 1986, under the bishopric of Ortega in Havana, the programmatic moment came for the Cuban National Ecclesial Encounter (ENEC). In this important conclave, the Catholic Church on the island established its social doctrine on genuinely Cuban programmatic bases, putting Father Félix Varela, with his compassionate, conciliatory and gradualist methodology; and José Martí, the greatest Cuban patriot, at the center of a projection that combines their natural cosmopolitan vision with the nationalist commitment to Cuba.

This projection was decisive as a guide for the changes in the position of the Cuban government, which faced by the religious disinhibition and the tact with which the religious communities had defeated atheism, by 1992 adjusted its policies by abandoning what was then an indefensible position as a State. Some analysts claim that in the 1986 ENEC, the Catholic Church under the leadership of Ortega pushed a door opened by Fidel Castro based on his conversations with Frei Betto, which is partially true. However, that obvious explanation that the revival of religious communities was knocking on the State’s door, would have been irrational for the government not to take it into account.

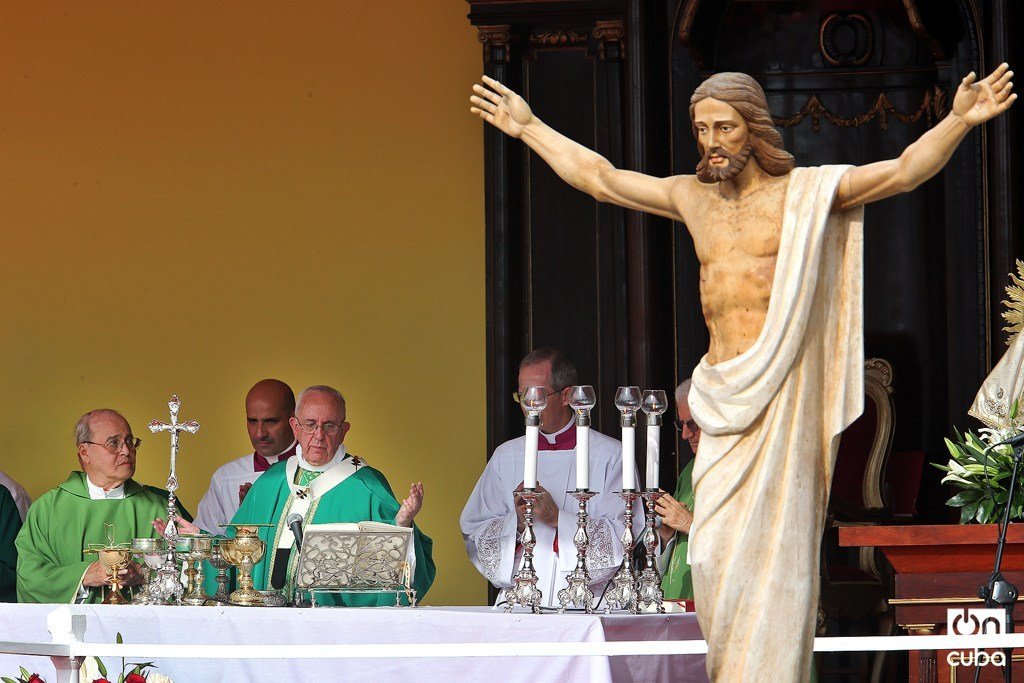

Since 1992 a new stage began in Ortega’s leadership in the Cuban Catholic Church and the country. The constitutional reform reinforced religious disinhibition and the return to the temples, accelerated by the difficult conditions of crisis Cuba experienced in the 1990s. In his position as cardinal, Ortega would be key in the historic visit of John Paul II to Cuba in 1998 and in the implementation of a comprehensive program before, during and after the papal trip. It would be the first of three papal trips, with an unusual continuity of purpose. Then Benedict XVI and Francis would visit Cuba, paying striking attention to the country based on the motto: “Let Cuba open up to the world. Let the world open up to Cuba.” Institutionally, Ortega’s work would leave the Church much better equipped from the doctrinal, institutional, educational and social presence points of view than at the beginning of his principality.

An area where Ortega’s work appeared in the foreground was the international one where his good offices accompanied the Vatican diplomacy in the understanding of promoting Cuban openings and reforms in sovereign terms based on the creation of a friendlier international environment toward the country. The Ortega cassock provided an essential mantle for the release in 2010 of opponents arrested in the spring of 2002 and sentenced to long prison sentences in trials challenged by important factors of the international community. The good offices of Ortega and the bishops, then backed by the Spanish government of José Zapatero, undid a knot for relations between Cuba and Europe that had been aggravated by the reinforced intransigence in Havana and the old continent, inflamed by radical opposition views in the United States.

Ortega knew that the wet blankets, contrary to reconciliation, would not forgive him for this. The act that the adversaries of his approaches organized in 2005 against Cardinal Ortega at the Miami airport was offensive. Those sectors directed against him and the Popes who visited the island insults that until then had only been reserved for Fidel Castro. Interestingly, Jaime never traveled again through the Miami airport, but found the best way to convince them of their mistake, improving relations with the Catholic Church in Florida, receiving multiple top leaders from Europe, Latin America and Canada, reinforcing Cuba’s international perception as a “country in change” that undermined policies of hostility and isolation.

As he revealed in his book Encuentro, diálogo y acuerdo. El papa Francisco, Cuba y Estados Unidos (San Pablo, 2017), Ortega would play a complementary but high-level role in the process of rapprochement between Cuba and the United States, which led to the agreements of December 17, 2014 between presidents Barack Obama and Raúl Castro. On another occasion, Ortega had meetings in the middle of the 2012 electoral campaign with the two Republican Catholic candidates for the presidency, Newt Gingrich and Rick Santorum, to favor a bipartisan approach in favor of exchange and informing those politicians about the situation on the island.

After Obama’s re-election, and by mutual agreement with Pope Francis, Ortega wrote the draft papal letter addressed to the leaders of Cuba and the United States, and with the approval of the Vatican, he visited the Cuban president, then resting in Cayo Saetía, and the White House, under the pretext of a presentation at Georgetown University. The two presidents who were secretly negotiating knew then that they had significant support, and that their opponents would have to come up against the Church.

His work resulted in the agreement of December 17, 2014. Upon requests from U.S. personalities and from other countries, who advocated unilateral statements on the subject of sub-contractor Alan Gross, Ortega explained patiently that his role was to create an environment conducive to reconciliatory solutions, not making declarations in response to unilateral pressures. Even when academicians, artists and intellectuals related or inserted in Cuban government institutions traveled to the U.S., and lowered the profile of the subject of the five Cubans imprisoned in the United States accused of espionage, Ortega called for looking at the issue with openness, reciprocity and mercy towards Gross and the five. On these bases a solution was reached, which unleashed much more than reciprocal humanitarian gestures: diplomatic relations between Cuba and the U.S. were reestablished.

An obituary on Cardinal Ortega could not be complete without referring to what was the Church’s most important movement from the point of view of its social doctrine in Cuba: the rescue of the legacy of Félix Varela. The Church, more than any other institution, set out to rescue the one who taught us first to think and think in Cuban: his championing independence, his proto-social Christianity, and his condition as a precursor to Martí’s thinking. If the great intellectual merit of this rescue corresponds to Monsignor Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, the institutional merit has its greatest architect in Ortega. At this time of structuring new economic systems and of thinking about constitutional and political reorganizations, Ortega never tired of remembering on the 150th anniversary of Varela’s birth, his warning to the new generations: “There is no nation without virtue, nor virtue with impiety.” Promoting a virtuous nation with mercy, saving himself and his circumstances, is his legacy.