Although less known ―and recognized―than their male colleagues, several women have made history within the Cuban press. Theirs has certainly not been an easy path; particularly for those who chose this path at a time when intellectual work was an (almost) exclusive fief of men.

To prevail they had to demonstrate talent, will and courage, and leave behind the many prejudices that weighed on women who preferred the heat of public life to the subdued tranquility of the family and home.

Domitila García, Ofelia Domínguez, Renée Méndez Capote, Loló de la Torriente, María Collado and Mirta Aguirre are some of the most well-known pioneers of women’s journalism on the island, a list that would be incomplete without Mariblanca Sabas Alomá.

Sabas Alomá, who was born in Santiago de Cuba in 1901 and died in Havana 82 years later, began her career in the press in 1918 in her hometown, where she collaborated with two of the main publications of the time: El Cubano Libre and Diario de Cuba.

Already in Havana, where she would move in the 1920s, she would gain relevance for her work as a journalist and, especially, for her ardent support for the emancipation of women, both in the press and in other public spaces, for which she would earn the nickname “champion of feminism.” She is remembered for her participation in the First National Women’s Congress, in 1923, and for her support for women’s suffrage and for the rights of working women.

Not only was she a member of the Women’s Club of Cuba, but also of other progressive organizations such as the Veterans and Patriots Movement, the Minority Group, the Anti-Imperialist League and the Anticlerical League, while participating, together with Julio Antonio Mella, in the José Martí Popular University.

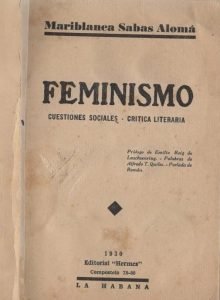

Poet and writer ―the book Feminismo, published in 1930, stands out among her works―, her journalistic work was wide-ranging and appreciated. Her signature appeared in important Cuban newspapers and magazines such as El País, Excélsior, El Mundo, Diario de la Marina, El Heraldo ―in which she promoted a section to respond to readers―, Avance, Prensa Libre, El Sol, Información, Social, Orto, Carteles and Bohemia. She also collaborated with publications from outside the island and was a radio commentator on the CMQ station.

Founder in 1938 of the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UEAC) and delegate to the Constituent Assembly two years later, she became minister without portfolio in the cabinets of the authentic governments of Ramón Grau San Martín and Carlos Prío Socarrás, becoming the first Cuban woman to hold such a high government position.

Opposed to the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, she supported the Cuban Revolution led by Fidel Castro and until her last days he insisted on exalting the role of women in society. As an example of her thinking and writing ―which, according to the scholars of her work, was characterized by a direct and pleasant style― I leave you with fragments of her text “Feminismo revolucionario,” in which she analyzes the scenario of women’s struggles in the first decades of the 20th century.

Let it serve, in addition, not only as an evocation of one of the great Cuban journalists, but also as a tribute to all women on March 8, when their day is celebrated worldwide.

***

Feminismo revolucionario (Excerpts)*

One of the most interesting aspects of feminism is the one that places two social classes face to face: the rich and the poor, the exploiting and the exploited, the one that enjoys all the comforts of life without producing, and the one that, producing, lacks the most elementary resources of health, comfort, culture and well-being in life. Indeed, the following question may be asked: is it more in the interest of working women to form, in the sector itself or as a separate sector, a single front of action with working men, than joining the ranks of active feminism, the latter limited to the struggle to obtain all the civil, legal and political rights that men still deny women?

Honestly, the sociologist can never approach feminism as a global problem, disconnected from other collective legal, moral, political, or economic problems, much less, as a single problem where the different needs of different women’s groups have the same solution. It is obvious that the problem of the working woman is not the same as that of the society woman ―the same class struggle between men, is present among women. Thus, it seems clear that although for the conquest of certain civil rights of a legal nature it’s OK for all women to form a single large front of action, however, when it comes to political or economic issues, they must join the men who are in the same condition. A viable formula: against men, when men are the masters. Together with men, when men are, like us, slaves struggling to conquer their independence. Against men, if men, as such, claim the persistence of an alcove feminism, purely sexual, full of morbidness, humiliating and sterile. Together with men, if men, penetrated by the painful reality of the exploitation of work, stand up against their exploiters, struggling to open the path to the “future without geographies” prophesied by Lenin.

Of course, the feminist movement is fundamentally revolutionary. We women, by rebelling against an established order of things, form on the left of a social process of incalculable transcendence, we have repeated time and again that we do not want emancipation as a synonym for licentiousness, but claim rights that we know are responsible for us to a great extent. More than men, because we suffer with greater intensity than them the consequences, we women rebel against a social structure overshadowed by falsehoods. We are tired of vegetating, lacking in personality, far from life. We modify, without distorting it, the Marxist theory of historical materialism, because women, wherever we fight —in school, the workshop, in the factory, in our own home— provide the invaluable gift of our great gentle spirit. A gentleness that does not exclude courage, gentleness that does not go hand in hand with humiliation. More than gentleness, we could say materialism. Each woman is a female in essence and a potential mother, although current living conditions strangle and distort the sense of motherhood. By incorporating ourselves slowly, but decidedly, into the activities of political life, of public life, we provide a wealth of pure ideals, of generous yearnings, of nobility of view, of enthusiasm for all that means collective improvement. We also contribute, that faculty that is increasingly rare among men —perhaps for having exercised it for so long without apparent practical result: the power of indignation.

Just as you can be a woman and practice civics, you can be a woman, very woman, and feel the whip of indignation. Life offers us multiple occasions to be indignant! First, it is our home, that which we generally call our home, where women are nothing more than poor things without soul and without conscience governed by father, husband, brother and even the son himself. On more than one occasion I have pronounced myself against that false “stability” of homes, proclaimed in the name of the rotten social morality. There can be no stability where there is a master who commands —he who is also unhappy, because he neither understands nor is understood, because he neither esteems nor feels esteemed— and a slave who serves….

The feminist struggle comprises three aspects: the economic aspect, the moral aspect, the political aspect. The problem of women’s work entails enormous importance. In Cuba, society becomes impoverished, largely due to the iniquitous exploitation of working women. Where they are least exploited is in the offices of the State, but even there they are not properly paid for their work. In commercial establishments, exploitation sometimes reaches the highest level. Few of them pay them well….

Biology, according to one of its most illustrious panegyrists, Dr. Gregorio Marañón, will continue to consider work as a normal function corresponding to the male…. And, sometimes, the most eminent biologists are far from being medium psychologists. They know the smallest piece of the human mechanism, and its wonderful gear. But they fail to penetrate the essence of the spiritual electricity that moves it. About women, the biologists know that we are naturally fit for reproduction, that the very high mission of conserving the species is entrusted to us. But of our spiritual life, of the needs of our state of mind, of the power of our thinking, they know very little, because not because they are scientists do they cease to be men, and men very rarely stop worrying preferably about the mechanical female.

(…)

Revolutionary? Yes! We Latin American feminists are revolutionary! We are revolutionary because we are women, because we are mothers, that is, because aware of our historical responsibility, we eradicate in ourselves the feminine, the humiliating resignation, the infamous passivity in the face of the empire of evil on earth! Women, let’s get down to it, that the reddish glow of a not distant dawn illuminates our victory! With us, free and strong, the men and women of the day after tomorrow. Against us, sullen and somber, the reactionary spirits, the cowardly exploiters of humanity.

* Excerpts taken from the blog Asamblea Feminista

Thanks for writing this! I did not know this and confirmed she’s actually related to me. So awesome! Thanks from Chicago.