Eusebio Quintana Macías looked at the tobacco plantation, while he drank water from the clay jug that kept the liquid cool. The view was magnificent. For a moment, the panorama resembled the young banana trees that he observed from the height of Lomo de Quintanilla, in his native Arucas, Gran Canaria.

In his journey through Cuban regions, he dedicated himself more than once to the cultivation of tobacco since he emigrated in 1909. His story was similar to that of thousands of adolescents and young people. In his case, with the money saved, he was able to buy a small farm in Paco, near the Cuéllar River, in the municipality of Ciego de Ávila, then part of Camagüey province.

Other immigrants, on the other hand, had decided to return to the Canary Islands and brought their knowledge, techniques and seeds of the aromatic plant there to promote cultivation, starting in the second half of the 19th century.

Although tobacco already existed in Cuba in pre-Columbian times, its cultivation for commercial purposes began to develop on the island in the 17th century, in areas near rivers in the province of Havana. Later, the plantings were extended to central and eastern regions.

Canarian immigration would play a notable role in the progress of this branch of the economy. There were towns, such as Santiago de las Vegas, founded by immigrants, who specialized in tobacco production. These tobacco planters had characteristics that favored them:

The islanders are industrious, with frugal habits, lovers of the land and livestock, they have the virtue of thrift, so rare among us, and they easily assimilate the way of being of our country people, who, ultimately, in their vast majority descend from the same trunk.

This is how Ramón María Menéndez would refer to it in his book Memorias de un enumerador. Regarding the topic, researcher Pablo Tornero Tinajero provides more elements:

The social core that was involved in jobs derived from tobacco growing at this time was fundamentally represented in Cuba by immigrant farmers. It was, in certain aspects, difficult for them to integrate into the economic life of the island, both because of the prevailing slave model and because of the very conditions of these immigrants. This is why they found a way out, occupying a short space of land, either rented or owned, and dedicating themselves to tobacco-related work. And precisely for them, because the tobacco plantation needed very little capital investment, few implements, and few tools, all of which were ideal for a farmer with limited resources. At the same time, the dedication to this work, smallholding, intensive, required a lot of preparation and care ― says F. Ortiz ― that sugarcane work is a craft and tobacco work is an art, which also required this type of farmer with special characteristics, both in the technical and human order.

The expansion into new areas was constant. A report from the Superintendent of the branch, in 1811, stated that there were 5,996 squatter tobacco plantations; 962 private ones; without being planted, 13,663 and 20,000 tillable crops (sic), on the banks of the rivers.

The trend continued in the first decades of the 20th century, with a strong presence of Canarian immigrants. As a sample, I quote what happened in Sancti Spíritus, according to studies by the historian Martínez Moles, cited by Alberto Galán:

With the advent of the Republic (1902), numerous growers from the Canary Islands flocked to the Sancti Spiritus region and invaded all the areas where cultivation was susceptible: the pastures were plowed, the mountains were felled, raising cultivation to a prodigious magnitude and millions of pounds of tobacco employed hundreds of families who were dedicated to the destemming and classification of the leaf in chosen establishments. Guayos, Cabaiguán, Neiva, Santa Lucía, Macaguabo, Guasimal, Bijabo, Manacas and Taguasco almost changed their characteristics from farming regions to tobacco centers… With the central railway, they did not expand much (minor crops) either, because the rise in freight rates nullified the profit, with the site people deriving their activities from growing tobacco, which promised a more secure income; but in which they were displaced by the Canary islanders.

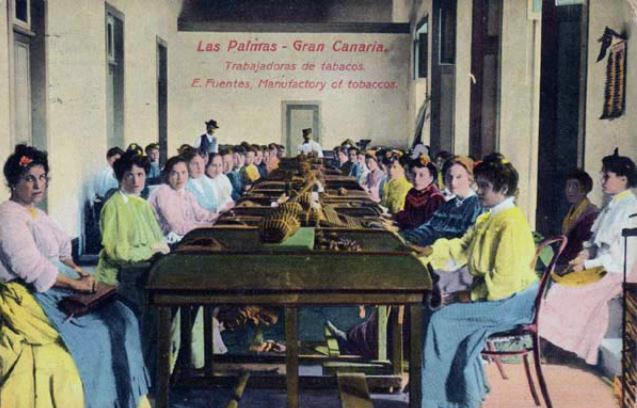

The presence of immigrants included the industrial part:

Cigar-making islanders could be found all over the island. For example, there were a large number of factories in the central area of Cuba owned by the islanders, especially in Cabaiguán, where their presence has been recorded as owners of small cigar factories integrated into the Cigar Makers Union that was founded in 1936. They owned factories such as El Guanche, Lucumí, Teide, Dorta, Nicaper, Vargas and, especially, Bauzá y Yanes. The latter, owned by Las Palmas farmer José Yanes Barreto in partnership with Don Juan Bauzá Vilela, employed up to 400 workers, being the largest cigar factory outside of Havana.

On the other Atlantic shore

When the export of cochineal entered into crisis in the Canary Islands, in the 19th century, farmers and businessmen considered that the adoption of the Cuban model, based on the cultivation of sugarcane and tobacco, would solve the problem. Since it did not require large capital to develop the tobacco plantations and would employ numerous families, it was an attractive alternative.

Furthermore, imported Cuban tobacco was part of everyday life, as it was sold in all the Canary Islands, and was associated in the popular imagination with the economic well-being of immigrants who made their fortune in the largest of the Caribbean islands.

At the end of the decade of 1827, some attempts were made that failed. At that time they had to ask for a license since the cultivation of tobacco was not allowed in the archipelago. In 1849, the Las Palmas City Council asked the central government for freedom for this production.

Pedro Socorro Santana, Chronicler of Santa Brígida, tells us that two years later, the schooner Adelaida, captained by Ángel Jesús Hernández, transported tobacco seeds for the first crops from Havana, without charging for the freight.

It is also known that the owner Manuel de Lugo received seeds from Cuba in 1850. He planted them in the Agazal country estate and the Cercados del Montemayor belonging to Gáldar and in Molino de Viento y las Huesas, municipality of Las Palmas. However, the cholera epidemic that hit the population prevented the success of the venture.

The engineer Juan de León y Castillo (1834-1912) contributed as a harvester and industrialist and also as a publicist by disseminating the Guía del cultivo del tabaco, printed in Las Palmas, in 1870.

Hoping to consolidate production, a group of investors decided to join the Porvenir Agrícola Society of the Canary Islands in 1874. The following year, the Spanish government purchased about 20 tons of tobacco harvested on the island for 4 shillings per pound. The historian Agustín Millares explains about it:

To more effectively attend to this special crop, a joint-stock company dedicated exclusively to promoting this industry was founded in Las Palmas, organizing a factory and requesting the government to purchase that product for national consumption. The company was established with great luxury of employees and offices, details of brands and counter-brands and promises of great benefits to shareholders. After many difficulties and delays, some consignments of manufactured and leaf tobacco were purchased (1875), which when taken to Madrid were unfavorably classified, because in his desire to please the selling partners, the director of the factory did not dare to reject the useless bundles. With this sad disappointment and with the deplorable result of the financial operations, the association was dissolved, with the individuals that comprised it obtaining no other benefit than some bad lots from a discredited industry.

After a while, the Royal Order of April 19, 1882, which allowed the consumption on the Peninsula of cigarettes made in the Canary Islands with tobacco harvested in that province, caused enthusiasm. Hopes were raised again.

The new crop had a greater presence in Santa Cruz de La Palma, the regions of Las Breñas, Mazo and El Paso. With capital investment from Cuba, factories such as La Africana, Flor de La Palma, El Trabajo, La Equitativa and La Golondrina were established. They were small businesses and industries founded by former tobacco growers who turned the island into the main tobacco producer of the Canary archipelago.

Luis Felipe Gómez Wangüemert (1862-1942), from La Palma and residing in Cuba, journalist, teacher, farmer and politician, was one of the returnees — in his case temporarily — who applied the experience assimilated in Pinar del Río.

In addition to creating two factories: La Africana (in partnership with Juan Cabrera Martín) and Flor de La Palma, Gómez Wangüemert organized exhibitions to promote production and edited the magazine El Tabaco. In the editorial of the first issue, he stated:

We seek the extension and improvement of tobacco cultivation and the procedures used to transform it into cigarettes, so that, once its undoubted excellence is known, it makes its way into all markets.

And since the Peninsula, since Spain does not produce tobacco and this island is currently the only Spanish land where it is cultivated and produced according to the practices of Cuba, we must direct our modest efforts to ensure that the legitimate La Palma tobacco is known in the peninsular territory and that the leaf tobacco be purchased from us for the national factories and the processed one for sale in the tobacconists of the Tenant Company.

His purposes were well founded: in 1906 Spain imported leaf tobacco for its factories.

Luis Felipe Gómez, promoter of tobacco cultivation in La Palma. Photo taken from the book “Wangüemert y Cuba, Centro de la Cultura Popular Canaria.”

In Tenerife, tobacco was grown in 1882 in the municipalities of Adeje, Granadilla de Abona and Vilaflor, with Marcial Melián Sánchez (1816-1891) standing out. He had lived in Cuba and when he returned, he brought back “the best seeds and the art of the perfect composition of the leaves of that sensitive plant, pure vice, which spread throughout Las Palmas, Telde, San Bartolomé de Tirajana, Santa Brígida, Arucas and La Aldea,” says Pedro Socorro.

In Tenerife he founded, in 1877, the La Afortunada factory; later he inaugurated another one in Santa Brígida, Gran Canaria, and created a warehouse in Las Palmas, on the corner of San Francisco Street.

Although in Santa Brígida the factory employed a small number of women, because not much labor force was needed, in agriculture it was different. Pedro Socorro specifies:

Life in the land of Santa Brígida revolved around tobacco and its collection involved the majority of the population, since it required the strength of almost all the arms in intensive days to the point that the councilors of the town hall, who did not stand out for their regular attendance at the plenary sessions, gave up going to the ordinary session when there was a tobacco harvest.

Leader in exports

With its ups and downs, tobacco production in the Canary Islands went through the 20th century. And today the La Palmas cigars enjoy international fame. La Primorosa is one of its factories. Of its origins it is said:

The current seeds arrived from Cuba in the 1940s; popularly called golden hair, its presence meant in the post-war period that many families could survive by growing a handful of tobacco, in a job in which all its members collaborated. The women, at night, stood guard over the seedbeds ― small tobacco plants ― with jachos, or torches, to prevent them from being attacked by the threads, worms that appear after sunset.

In 2023, 59% of Spain’s tobacco industrial activity was concentrated in the Canary archipelago, where 23 local companies and subsidiaries dedicated to this sector were active. It was estimated that the direct contribution of tobacco to public administration revenue would be around 248 million euros.

It employed nearly 4,500 people, a figure that represents 18.8% of Canarian manufacturing employment and 11.5% of total employment in the industrial sector. Tobacco exports, estimated at around 203.6 million euros, moved to first place for the first time in history by displacing bananas, one of its traditional products.

Who would have imagined this outcome in the Atlantic adventure of Cuban tobacco? That island traveler became a tangible seal between two archipelagos, connected by centuries of common history.

________________________________________

Sources

- Ramón María Menéndez: Memorias de un enumerador, printing house Avisador Comercial, Havana, 1907.

- Pablo Tornero Tinajero: “Inmigrantes canarios en Cuba y cultivo tabacalero. La fundación de Santiago de las Vegas (1745 – 1771)”

- José Alberto Galván Tudela: “Migración insular y procesos de trabajo de los canarios en Cuba (1900-1930.” 12th Colloquium of Canary-American History, 1998.

- María de los Reyes Hernández and Santiago de Luxán Meléndez: Retratos de promotores del cultivo del tabaco y representaciones plásticas del hábito placentero en Canarias (siglos XIX-XX).

- Pedro Socorro Santana: Memoria de la fábrica de tabaco de Santa Brígida.

- Alberto Galván Tudela (Ed.): Canarios en Cuba. Una mirada desde la Antropología, Gráficas Sabater, Tenerife, 2007.

- Miguel Suárez Bosa and Francisco Suárez Viera: “Emigración y actividad empresarial canaria en Cuba, 1850-1950.” Sequence, no. 87, Mexico, Sep./Dec., 2013.