There’s a faded color on the Guantánamo mountainsides of the Nipe-Sagua-Baracoa Massif. Stationed for almost eight hours in the region, Hurricane Matthew changed the perspective of the natural landscape. Now there is only a dull tinge of ochre.

The mercilessness of the hurricane destroyed palm trees, frightened away animals, tore at mountains, erased roofs and walls. What Matthew was unable to take with it was the survival instinct. The protection – organized by the Civil Defense, well-connected to citizen and ecclesiastic solidarity – in the face of climatological debacles is legitimized in Cuba.

It’s astonishing. That there wasn’t a single death in Cuba after the impact of Matthew is like a miracle or a plot worthy of science fiction. That is the opinion of Rodolfo Hernández, a mechanic by profession and amateur meteorologist, who attentively follows every detail about all the storms and depressions affecting the island.

“Suffice it to look at the photos of what Matthew did in Baracoa and in Maisí,” he says, “to calculate the force of the hurricane. It was a disaster, it flattened out houses, it tore off balconies from buildings, but all the persons were saved. The truth is that things were well-organized.”

The havoc wreaked has made people return to the rivers on the road to Baracoa and there to Maisí, where they went to wash the clothes they were able to conserve or to freshen up from the intense heat of the days that followed the strong winds.

The Concha Lighthouse of Maisí Point conserved each one of its parts and won its individual fight against Matthew. Inaugurated on November 19, 1862, the Concha will continue guiding the vessels on route through the Windward Passage.

The bridge over the mighty Toa River, whose force destroyed the concrete structure that sustained the foundations, will also be reborn. And the thing is that the rugged, the desolation will necessarily be left behind. And the fish will again bite in the bay of Mata. Life will go on. The dull, by force, eventually will give back a landscape that does not belong to it.

But today Matthew is still real.

Rebuilding

To get to Baracoa one has to pass through Miel River and encounter the Yunque, that geography’s most singular mountain. La Farola highway is the means to get to the very spot where Cuba’s first township was founded.

Alejandro Hartmann is that city’s historian. His eyes take in the landscape and confirm the damages caused by Hurricane Matthew in Baracoa’s built heritage. The historian lists many of the cyclones that have run aground in the old city. “We have been reborn from all of them,” he points out.

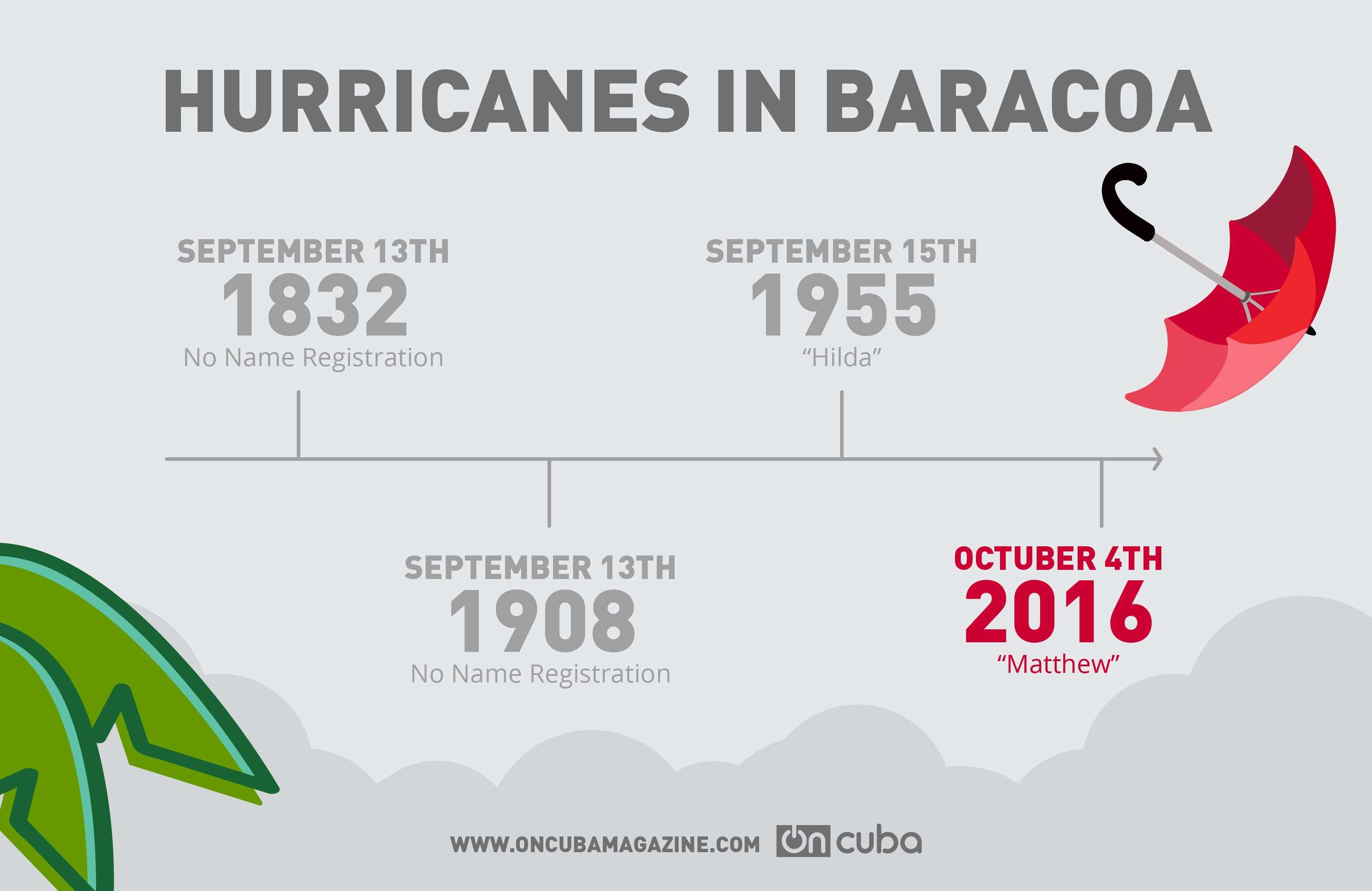

According to Hartmann, the Chapter Minutes of the Town Hall of the First City state that several meteorological phenomena hit it. He indicates significant dates like September 13, 1832 – although he doesn’t specify the name of the hurricane -, September 14, 1908 (it is stated in documents that a climatological phenomenon left the second part of the Castillo Hotel roofless, something it also lost with Matthew), and he recalls Hilda on September 15, 1955.

“Ike, in 2008, was close, just 49 miles to the northeast of the city, and it partially affected more than 9,000 homes. Matthew was actually the strongest hurricane. There is no previous documented information that indicates that a phenomenon of this nature has affected us so much. We think that out of more than 29,000 homes, 95 percent of them have been affected.

“All the efforts are already being made. We just came from a meeting with the government and we learned that our network and the National Heritage Council of the Ministry of Culture assured us that all the financial facilities exist to reestablish Baracoa’s architecture, which does not have an opulent style like that of Trinidad and Camagüey, or Havana’s columns or the presence of the Caribbean in the Santiago de Cuba urban planning, but it is our vernacular architecture, with its own personality,” the historian explains.

Juan Mucoba Avivar, assistant director of the Office of the Santiago de Cuba Curator, considers that the principal damage to the built heritage has been the loss of the houses’ roofs. He affirms that there’s an institutional will to give back to Baracoa its splendor. “We don’t want to demolish and build glass and concrete blocks, but rather we want to place in each site what it should have. The house that had a colonial roof, well, we want to have one again. If its large windows and balconies were from that period, it will have an exact restoration, the same.

“Because that is Baracoa’s identity. And it was an experience acquired in Santiago during Cyclone Sandy. Heritage is history. If history is forgotten, the nation is forgotten.”

Clinging to the cross

The only known Cross from Christopher Columbus’ expedition that remains in Cuba is intact. Matthew, the category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale that shook Baracoa, was not able to destroy the old relic, a sign of the Catholic evangelization of the Spanish metropolis on the colonized island.

“Columbus’ Cross (the only one conserved out of the 29 he brought on his trip) continues guarding the parish church, for now, until everything is stabilized,” Father Mateo, the parish priest of the Baracoa church, which Pope Leon X built as the first bishopric and Cathedral of Cuba between 1516 and 1523, says with a gesture of faithful devotee.

The priest speaks of the miracle he and several of his parishioners witnessed given that the entire church withstood a powerful cyclone and protected the objects necessary for the liturgy.

“It’s a miracle. What was most impressive was when the eye of the hurricane passed. We received a family, three persons in wheelchairs and some children who had lost their homes. They stayed with us,” says Father Mateo.

He was one of the first to go out to the nearby communities and he says he has seen how the cyclone has destroyed entire houses. “We have noticed that when the people see us they embrace us and cry. They are all trying to fix their roofs, to have a small room to store their things and they want some root vegetables to boil, some fruit. The most difficult part is the food; at least something is already getting to the city.”

Priest Alberto agrees with this and affirms that in Maisí the most pressing problem is the lack of potable water. “It already existed before Matthew. Sabana, for example, doesn’t have a fluid supply. The people, including the church, use rainwater and store it in cisterns. But these receptacles are contaminated and the cyclone also destroyed the canals,” he laments.

And he adds: “I have a roof and a bed, but there are people who have lost everything, whose houses have been flattened out and they try to recover the boards or cardboards to build a small room. But the people have hope and everyone is coming to life. God will not fail us. It is the time to unite and give priority to life. Then we’ll make do little by little.”

Electricity workers

Ricardo Hernández Pérez is confident that his Afro-Cuban religion necklaces will protect him while he works in restoring the electric system in Baracoa. “I feel safe with them,” he says while he squeezes them.

Ricardo has already participated in almost 10 recovery works after hurricanes. Today he heads one of the investment brigades of the Ciego de Avila Electric Union. He and his team – “stronger than any cyclone” – have experience in the repair of the “deadly” electricity lines after a cyclone.

Matthew devastated daily normal life, and took with it any contact outside of Baracoa. That’s why Ricardo thinks that fast action is the best gesture in the face of destruction.

His job consists in “reestablishing power lines so people can have electricity in their homes.”

Alexei Rodríguez gets ready during the hurricane season to tour Cuba and help as an electricity worker to mitigate the havoc wreaked by those phenomena. A resident of Ciego de Avila, Rodríguez has worked in the recovery after three hurricanes: Gustav (Pinar del Río), Sandy (Santiago de Cuba) and Matthew (Baracoa, Guantánamo).

Dariel de Dios Rodríguez is not afraid of electricity. “We train for this, we study…. We pass courses. If you like it (the work), you stay,” he affirms decisively. In 10 years he has helped communities after three cyclones from his work in the Ciego de Avila Electric Union.

The flood caused by the hurricane also dragged with it the optical fiber cable, essential for the region’s communication. However, everything was restored thanks to the work of two brigades of communication workers – one from Holguín and another from Guantánamo –, with the help of the neighbors.

Raúl Capote Fernández, director of institutional communication of the Ministry of Communications, told OnCuba how it was done. “They came up with the idea of using a barge, fixing a tensor and putting up two posts from one side to the other of the river,” says Capote, who highlighted that the action was carried out when the river was still flooded.

“Thanks to that there is communication in Baracoa: the land line and the cellphone network, which is reinforced with the bringing over of a base and the fly away, which allows for increasing the capacity.”

Words on the road

Matthew’s night in Cuba, reproduced in the minds of those who lived it, is tangible, visible, it hurts. These are words collected on our road. They are some of the voices found following the hurricane’s trace.

The herds

Almost the entire community raises goats here. What has happened with the animals has been disastrous. Almost all of them were lost. I hid mine in my home’s bathroom. I didn’t have many, just 10 or 12 goats – here there are persons who lost about 20 of them. The storm and the cold killed them. I was left with just a few, four she goats. But there’s hope, my neighbor was left with male goats….

Freddy Fernández, 50, Maisí Point.

A fierce hurricane

They say the roads were in a very bad state and now (October 8) is that trucks are passing…. So many cyclones have passed through here and a cyclone like this one had never been seen before. It was a hurricane. Nature is like this, but we have to have faith. There are no communications. They’re fixing that….

We built a small room there, with a small bed. Because the problem is that all the mattresses were soaking wet.

In the grocery store the grains are wet and we didn’t want to buy them. We said: “What for?”

Neither has the delegate helped. They say he is sick. Before this he wasn’t sick and after this his knees have given out.

Vilma Gaínza and her neighbor Ana Lambert, Baracoa to Maisí highway.

The ‘Lobo’ will return to the sea

The best thing we are left with is hope. We were already told they would help us. My ‘Lobo’ was very old. I changed it for another smaller one. With it I fish for dorado, swordfish, sharks…. We have a contract with the Baramar fisheries enterprise and we sell them our productions.

At times the business does well and at others not so much, because it doesn’t depend on us but rather on nature. But the fish are already biting. We already caught quite a few yesterday [October 8]. It has to do with the bad weather and that the State estimated that we could not go out fishing, there are some events that are preventing us from going.

We’re going to get back on our feet. I think it will take a bit. The situation is critical. It’s Baracoa, Imías, Maisí, San Antonio del Sur…. It’s as if herbicide had been spread over all of Baracoa. Thank God it [Matthew] didn’t take off a single one of my home’s roof tiles.

I think the aid will help the town get back on its feet, although I have heard that some persons are leaving, they are abandoning it. But I think that those of us who stay will do something for the town.

Franklin Aguirre Machado, a fisher from La Playita, Baracoa.

Eddy Rodríguez Robaina and his family, in Manglito, Baracoa to Maisí highway:

Reporters: Yelanys Hernández and Eric Caraballoso.