Nowadays there are at least 300 Cubans in Nuevo Laredo. And every day there are more. They were all on the road when Obama changed the rules of the game. Almost 100 of them who were in Tapachula – border between Mexico and Guatemala – were deported and there are rumors that something similar could happen with those who are in Turbo, Colombia. Those who have already surpassed that barrier continue on the road to the border, which for the time being is not showing signs of deportation or of opening up to the north.

Eight out of every 10 Cuban migrants in Nuevo Laredo are men. A few brought their children, those who did so made shorter trips: from Havana they flew directly to some Mexican city and from there to the border. There’s a woman who is about to give birth, she would have gotten pregnant during the journey but she doesn’t want to talk about that.

Once at the border the Cubans chose the AMAR shelter because of it is big and because by January 12 there were only a few migrants – Hondurans – staying there. The Cubans have a premise: whether it is to cross to the United States or to return to Havana it’s better to stay together. That’s why the communication that started going around among the migrants recommended not going to another border that wasn’t Laredo and that’s why they all go to the same place to sleep.

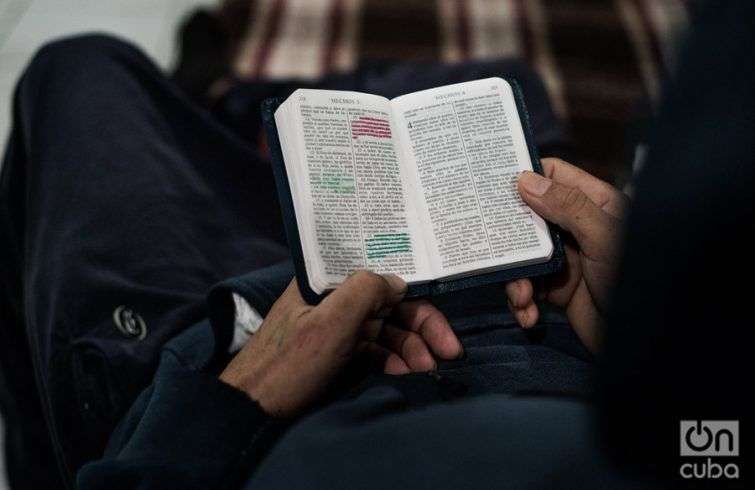

AMAR is a mixture of shelter and Evangelical Church.

***

The main room smells of humidity. It is some 30 square meters. Against the four walls there are 20 three-level bunk beds and in the space in the middle some beds, mattresses and mats on the floor. Seventy people rest there. It’s the room that first fills up although “there’s always room for more,” the Cubans who inhabit it say.

“There’s no small shelter when the heart is big, let all those who want come,” Joel, a physical education teacher from Havana, says to OnCuba, emphasizing the silence between each word. The beds are close to each other, you just have to stretch an arm to touch the back of the person beside you.

To get off or on the second level beds you have to hit the ground. “To get off of there you have to move like a worm,” they joke. They have mattresses of all sizes and years. The high ceiling lessens the human heat but the lack of windows makes it difficult to have oxygen.

The bunk beds have three levels, those who are at the top are benefitted with a bit more of air. Photo: Irina Dambrauskas.

The gym smells of roast chicken. Someone is using the barbecue in the neighborhood and the Cubans find out. To enter the main room they have to cross this gym, which has the size of a basketball court, with sheet metal ceiling and large windows covered with plastic that lets in the night dew.

Winter in Nuevo Laredo is not very hostile, a minimum temperature that doesn’t go down more than 10 degrees centigrade.

There’s a breeze and it’s cool.

The gym has been transformed because of the wave of Cubans in another dormitory. There are some 30 persons sleeping there on mattresses on the floor with blankets that instead of going on top are placed on them, they do not cover the guests, they barely isolate the cold tile floors from the worn-out mattresses.

This site is also a church. During the day – at 12 noon and 7 in the evening – the gym is where the mass is held.

One of the corners of the gym smells of shampoo. That’s where the washing up sector is located, with sinks and showers. The restrictions are very precise; the schedule for showering is from 19.30 to 22.00. Ismael Rodríguez – who arrived in Nuevo Laredo only an hour after the change in U.S. policy – took off his clothes, opened the shower and soaped himself. Pastor Aaron discovered him right there and turned off the water.

“The schedule for washing up starts in 15 minutes brother,” he told him.

Ismael stayed waiting those 15 minutes all soaped up. He got used to waiting.

There are other rules: “No running, no shouting” and, as happens in the Nazareth shelter. “There are orders to hand over the cell phones when entering the shelter.”

***

Laredo used to be a single one. It was founded in 1775 as part of Nueva España. Later, with independence, it became part of the Mexican Republic. In 1840 Laredo was a country; they declared themselves independent and proclaimed the Republic of the Río Grande that was again annexed six months later. Later, when the current border lines were drawn up in tune with the Rio Grande – in 1846 – the city was left on the Mexican side. Then a group moved to Mexico and in 1848 founded Nuevo Laredo. If Donald Trump keeps his promises in a short while a wall will divide both cities, in addition to the river.

Nuevo Laredo is full of solitary people, with the Cubans. Hundreds of thousands of migrants have passed through there for decades, especially Central Americans. The Cubans were not noticed: they crossed the bridge, placed their dry feet on U.S. territory and that’s it. They couldn’t afford to spend time getting to know the beautiful city perhaps for lack of architectural criteria, the prowling military trucks, the taxi drivers who worked with the paramilitary and the immanence of the Zetas.

***

Carlitos, one of the few migrants of the Casa AMAR who is not Cuban but Honduran, a victim of the Zeta mafia, is resting in the shelter after he underwent surgery on his leg. Photo: Irina Dambrauskas.

The wave that crowded them on the border awoke the sensitivity of the people of Nuevo Laredo. Not counting the aid they get from the Cuban Americans, which is a lot.

The Cubans got there in winter, a time that can be withstood. The minimum is usually 10 degrees and the maximum can reach 30 degrees. If they remain there until the summer they will have to suffer the maximum temperatures of 45 degrees.

On the U.S. side the first thing there is when crossing the border is a bus terminal that has destination covering hundreds of cities south of the United States, almost no migrant crosses to stay in Laredo.

The iron bridge that connects the old and Nuevo Laredo overflies the Rio Grande which has strong currents. It is 30 meters long and sufficiently wide to have two lanes for cars and a pedestrian way to come and go. There is a permanent flow of persons: on the U.S. side fuel and clothes are cheaper, on the Mexican side the supermarket and the dentist are more economical.

When going from Mexico to the United States there is a strict immigration control but no one checks the baggage, they don’t even pass it through the metal detector or drug-detecting dogs. From the United States to Mexico, on the other hand, there’s a control of baggage but no immigration control.

***

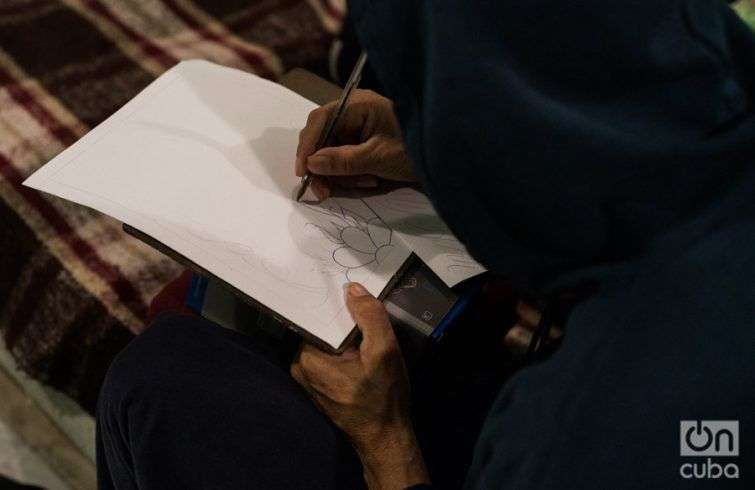

The shelter’s kitchen is used to wash dishes and the shelter’s employees take care of that. The oven, due to the amount of external donations that get there, is used very little or never: at the most to heat up some donation. There is no fighting, no shouts, no out of place comments. There is a tacit agreement to keep up the good humor. They make jokes, they remember passages about when they were on the road, they list in their talks what they like about Cuba.

They constantly talk of a freedom they didn’t have before: “What we are doing here, we couldn’t do in Cuba,” “What we’re saying here, we couldn’t say in Cuba”….

Cuban migrant getting ready to sleep on a mattress on the floor of the AMAR shelter. Photo: Irina Dambrauskas.

Women have a separate room with a bathroom they all share. In a 15-square-meter room the almost 20 Cuban women get organized to wash up and they go to bed early. Lights are out at around 10 p.m. and the shelter is silent.

At 7 in the morning of the following day they all get up to have their donated milk with coffee and crackers, they will get on the pastor’s pickup truck to go to the corner of International Bridge 1.

And that’s how it’ll be until someone gives them a visa, or a deportation order.

Follow this OnCuba series from Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, as well as our complete coverage of the immigration crisis: