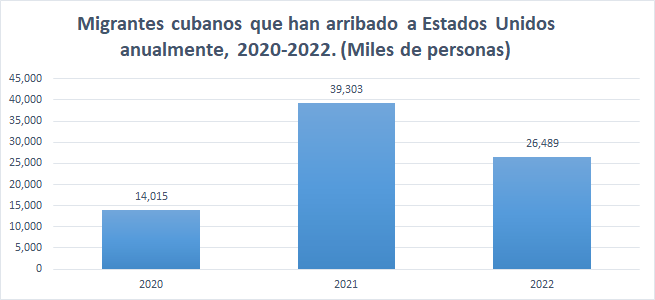

We are experiencing another migratory wave of Cubans to the United States. This is confirmed by data from the recently published report by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP).1 According to this organization, in the first three months of 2022, 47,431 people of Cuban origin have arrived at the borders of that country, a volume slightly higher than all those who arrived in Fiscal Year 2021:

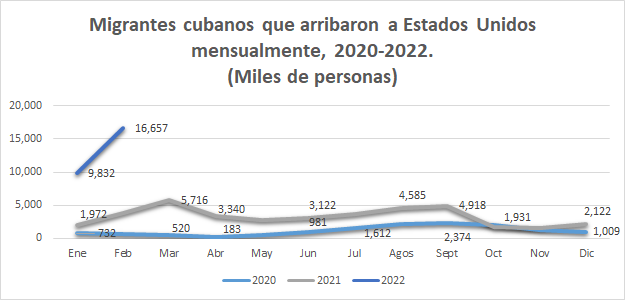

In February of this year alone, 16,657 people of Cuban origin arrived in the United States and, in their vast majority, through the border with Mexico (around 99%). The accumulated amount by fiscal years shows the following trend:

In addition, the increase in emigration by sea has been verified in relation to previous moments and, although it is not equal to the volume registered during the years corresponding to the process of normalization of relations between Cuba and the United States (2014-2017), the trend is increasing, according to information from the United States Coast Guard.2

In relation to the migratory flows that arrive through the Mexico-United States land border and thanks to the information through stories and interviews offered to the author of this text by migrants on their journey to the United States, we were able to find out that they are people who are traveling with family members and/or friends; they use “polleros”/”coyotes”3 or trusted people who help them successfully reach the border with the United States; and in the vast majority of cases the migratory itinerary to “cross the line”4 has involved crossing several countries and even half the world and a long time.

The diversity of trajectories is explained by the moment in which it was decided to migrate; the economic, social and information “capital” or “assets” available; and entry restrictions to other states, a fundamental lock to overcome after the elimination of exit permits for the vast majority of Cubans after the immigration reform of 2012.5 Thus, the complexity of the trip is closely related to available money, information and networks; the country that makes it possible to start the journey; the number of borders to cross; and a whole string of challenges and pitfalls that include, from geography to the political, social and humanitarian conditions of the territories through which they travel.

As is widely known, the impossibility of legally entering the United States from Cuba due to the closure of the U.S. Embassy on the island during the Trump administration, the enormous difficulties of doing so by sea after the agreements between the two countries in 1994,6 and the growing difficulties in obtaining a visa in the nations closest to the borders with the United States,7 has prompted the diversification of routes to arrive, sooner or later, on U.S. soil. Thus, many Cubans travel to South American countries such as Ecuador, Brazil, Chile or Uruguay to start a “long march” full of dangers and pitfalls; they cross nations openly hostile to irregular Cuban migration, such as Panama and Nicaragua; or they begin the journey through distant Russia, which does not require a visa for islanders but in whose journey the costs and problems associated with the distance to travel increase substantially, not to mention the existence of events that can take transit migration by surprise , as is the case of the war between that country and Ukraine which, unfortunately, is being suffered by many Cuban compatriots now.8

In these complex and long journeys, island migrants make use of “polleros” or “coyotes,” people who are part of the plot of human displacement between borders, who can make the road viable or cut it short, depending on the information, the money or the luck they have. Once the complicated chessboard of insecurity, surveillance and corruption that migration faces on these dangerous paths has been overcome, the Cubans arrive at the border with the United States and, unlike previously before the repeal of the “wet foot/dry foot” policy or the launch of the “Stay in Mexico” Program, Cubans who arrive in the United States irregularly enjoy a tolerance period. As confirmed by the experiences of newly arrived migrants this year and based on the information provided by the U.S. government, it is expected that the asylum application will be easier and faster.9

The United States has been failing for several years to comply with the agreement to grant 20,000 annual visas to Cubans residing on the island. In September 2017, an almost total closure of the U.S. Embassy in Havana was announced, which still remains, despite the announcements of a gradual reopening. The family reunification program is paralyzed.

The impossibility of having access to legal emigration, coupled with the sustained deterioration of living conditions on the island and the “limitations to creatively integrate political and generational differences,” as expressed by one of the migrants interviewed while passing through Mexico, plus the privileged treatment for the illegal emigration of Cubans in the U.S., may indicate that, in the coming months, a significant volume of compatriots will arrive to the most important “migratory line” in the world: the border between the North of Mexico and the South of the United States. United States.

***

Notes:

1 Available here, consulted on March 17, 2022.

2 According to this organization, 838 interdictions took place in fiscal year 2021 and 800 so far in 2022, compared to the 49 in 2020 and the 313 in 2019. Regarding this, click here.

3 Both terms refer to people who manage and make possible, in exchange for money, the transit through the territory of a State of people in an irregular situation or who are considered illegal.

4 This is also how the border between Mexico and the United States is known.

5 On October 16, 2012, the Migration Law was amended and approved by Decree-Law No. 302 of the Council of State of the Republic of Cuba. Included among the main modifications implemented is the elimination, except in specific cases, of the restrictions on leaving the country, in force since the beginning of the Cuban Revolution.

6 As part of the negotiations between Cuba and the United States as a result of the 1994 “Rafters’ Crisis,” a binational migratory agreement was signed that, to this day, remains in force and postulates, among other actions, the commitment to return to Cuba every Cuban who is captured on the high seas to discourage illegal migration. See in this regard, Ruth Ellen Wasem, “Cuban Migration Policy and Issues,” CRS Report for Congress, January 19, 2006, available here, consulted on March 17, 2022.

7 “SRE abre investigación por venta de citas en embajada en Cuba,” in López Doriga Digital, March 26, 2022, consulted on March 26, 2022.

8 See in this regard, “Cubanos varados en Rusia, Bielorrusia y Ucrania en plena Guerra,” in DimeCuba, March 14, 2022, consulted on March 17, 2022.

9 This March 29, a reform to the migratory policy was published (it will come into effect 60 days later) with the aim of speeding up the process of granting asylum at the border, according to some reports actions are already being taken to free migrants from immigration prisons people of certain nationalities, such as Cubans, Nicaraguans, Venezuelans and Colombians. See in this regard, Callie Patteson, “DHS orders Cuban, Venezuelan, Nicaraguan, Colombian migrant release: report,” March 24, 2022, consulted on March 25, 2022.