One month after the beginning of the monetary reorganization in Cuba, many doubts, criteria and dissatisfactions persist in the population. This, despite the fact that since the announcement made on December 10 by the Cuban president, the authorities and the media of the Island have dedicated numerous spaces to inform and explain the measures, changes and rectifications adopted as part of this process.

In particular, the prices of the different products and services―both state and private, official and informal―have been in the sights of many since the beginning of the reorganization became known, and still remain so today, even though not all of them rose or increased in the same way. Therefore, we have thought it appropriate to offer our readers a look at this controversial issue that directly affects the pockets of Cubans and reflects, like few others, the contrasts of a step that both the government and the specialists considered essential―but at the same time complex―to eliminate existing distortions in the Cuban economy and promote its long-awaited take-off.

In a first installment, together with a necessary introduction in this regard, we approached through graphics the prices and rates of electricity, gas, drinking water and sewerage, essential services in contemporary life that, as it is known, in Cuba are managed by the State and are, to a greater or lesser extent, subsidized by it. These services are included―from a rationality approach―in the amount of the basic basket, estimated by the government at 1,528 pesos (CUP) and whose calculation served as the basis for the increase in wages and pensions.

To arrive at this amount, which coincides with the established minimum pension―for those who previously received up to 300 CUP―, “a coherent, integrated and harmonious analysis was made of what a person should consume in goods and services and a rate was set,” as explained in mid-December by Minister of Domestic Trade Betsy Díaz Velázquez. However, in the face of criticism and comments from the population, who soon realized that their math did not add up, some prices initially set by the government have undergone adjustments and rectifications—those of electricity among them—and others were maintained “under study,” according to the authorities.

With the ration card

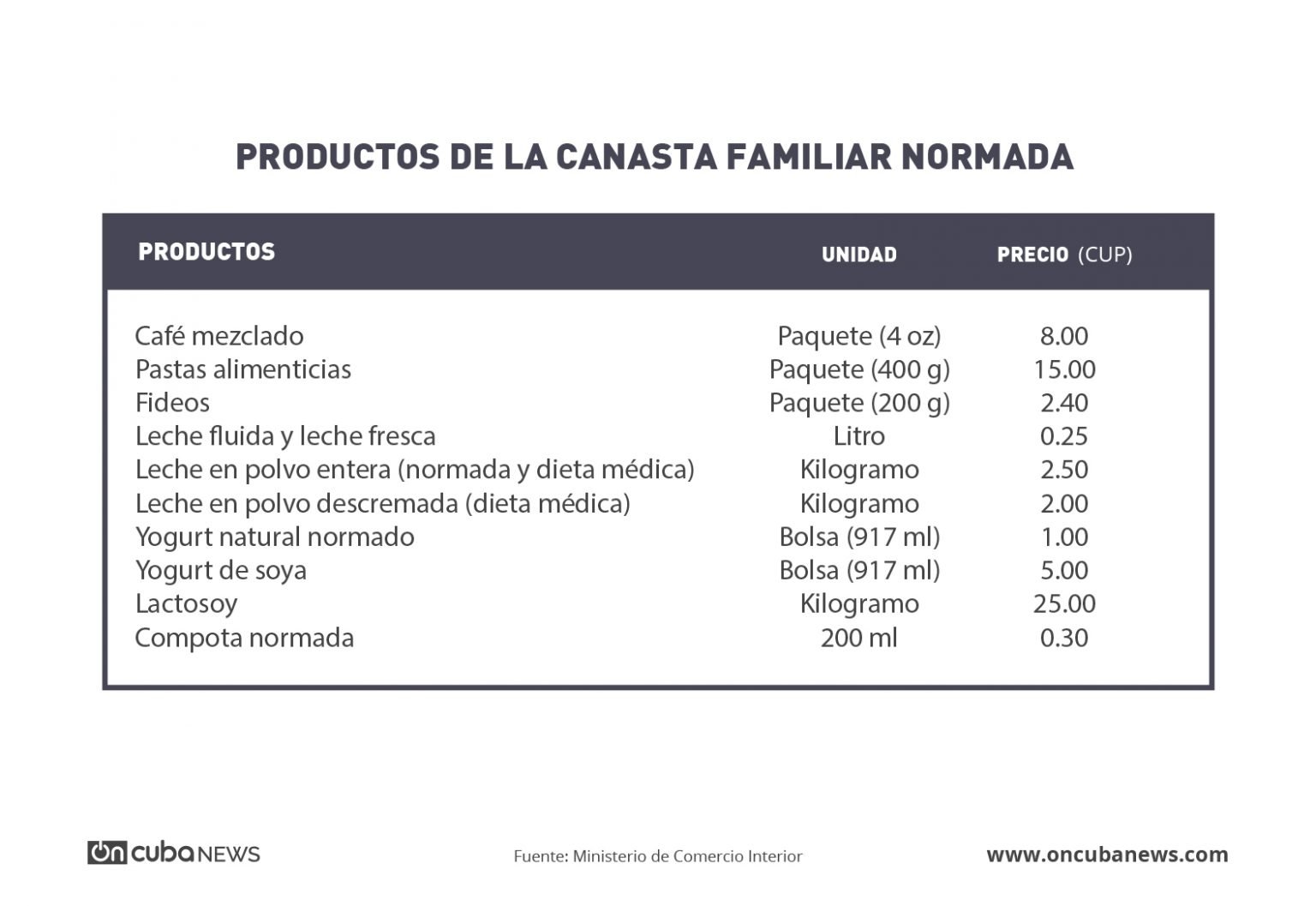

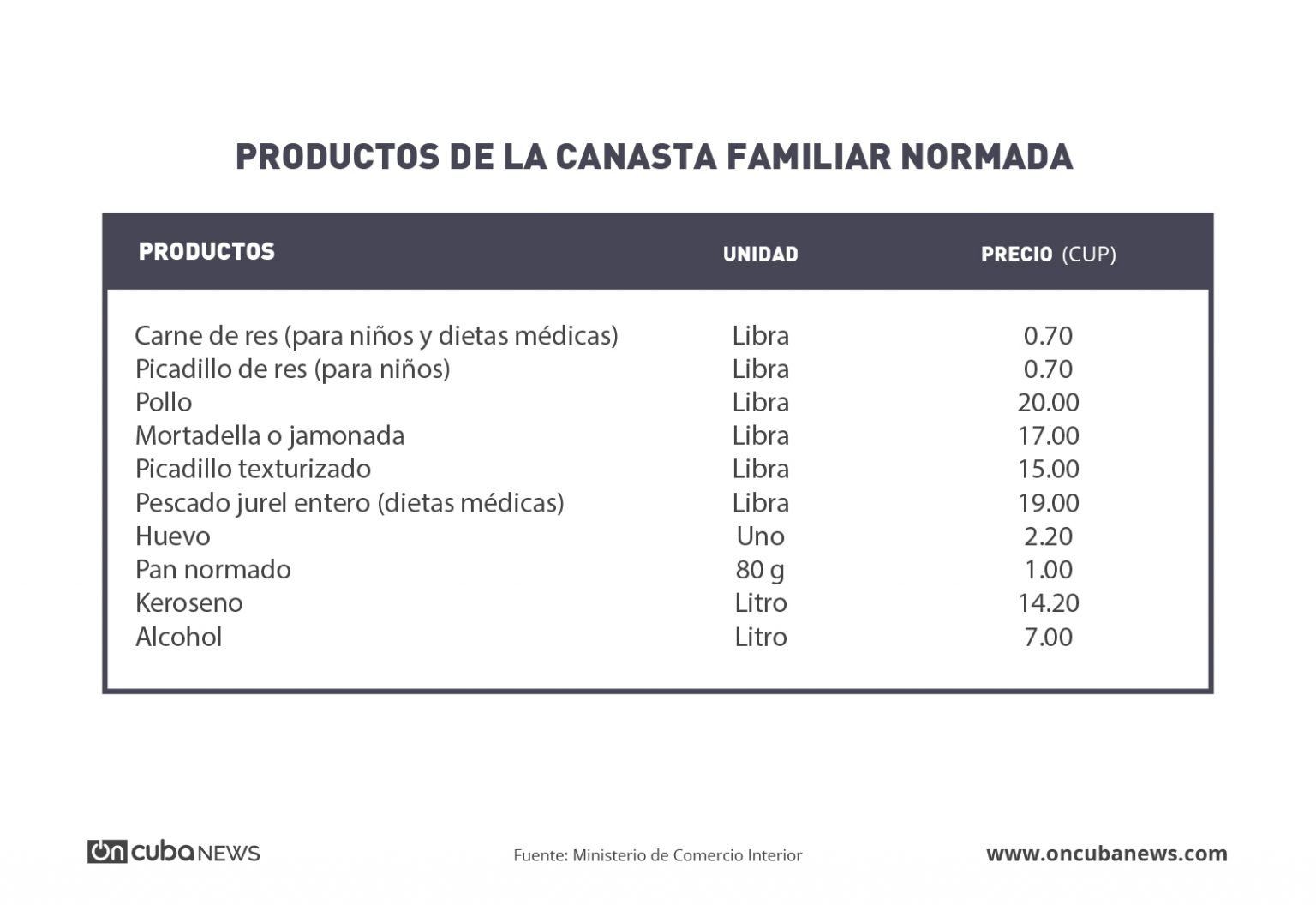

Vilified and loved, a source of ridicule and concern, the ration card survived, against many predictions, the monetary reorganization. What didn’t survive were the prices of the rationed products that are bought with it. In reality, most of them, since those of some foods intended for children—such as milk, compote and meat—and the diets for pregnant women and the sick did maintain, at least for the time being, the state subsidies that all products “on the ration card” had until December.

In total, the rationed family basket is still made up of 19 food products and four non-food products, only that its value rose from around 18 CUP per person to about 180 CUP. It is not surprising that, calculator in hand, many Cubans, in particular those from the largest families or those with low incomes, have aimed their darts against this increase and some have chosen to apply for some aid or social assistance to cover all expenses that this process entails for them and their families.

However, the authorities have also pointed to that, explaining that the reorganization, as part of the economic reforms designed by the government, pursues “the gradual elimination of undue gratuities and excessive subsidies, under the principle of subsidizing needy people and not products,” something that is intended to continue “in correspondence with the economic situation of the country and people’s income.” The rationed basket has thus remained more as an equitable distribution method—something that already was like that, even with its well-known shortcomings—than as a protection and subsidy mechanism for the whole of society, something that clearly the Cuban economy today cannot allow itself.

And without the ration card…

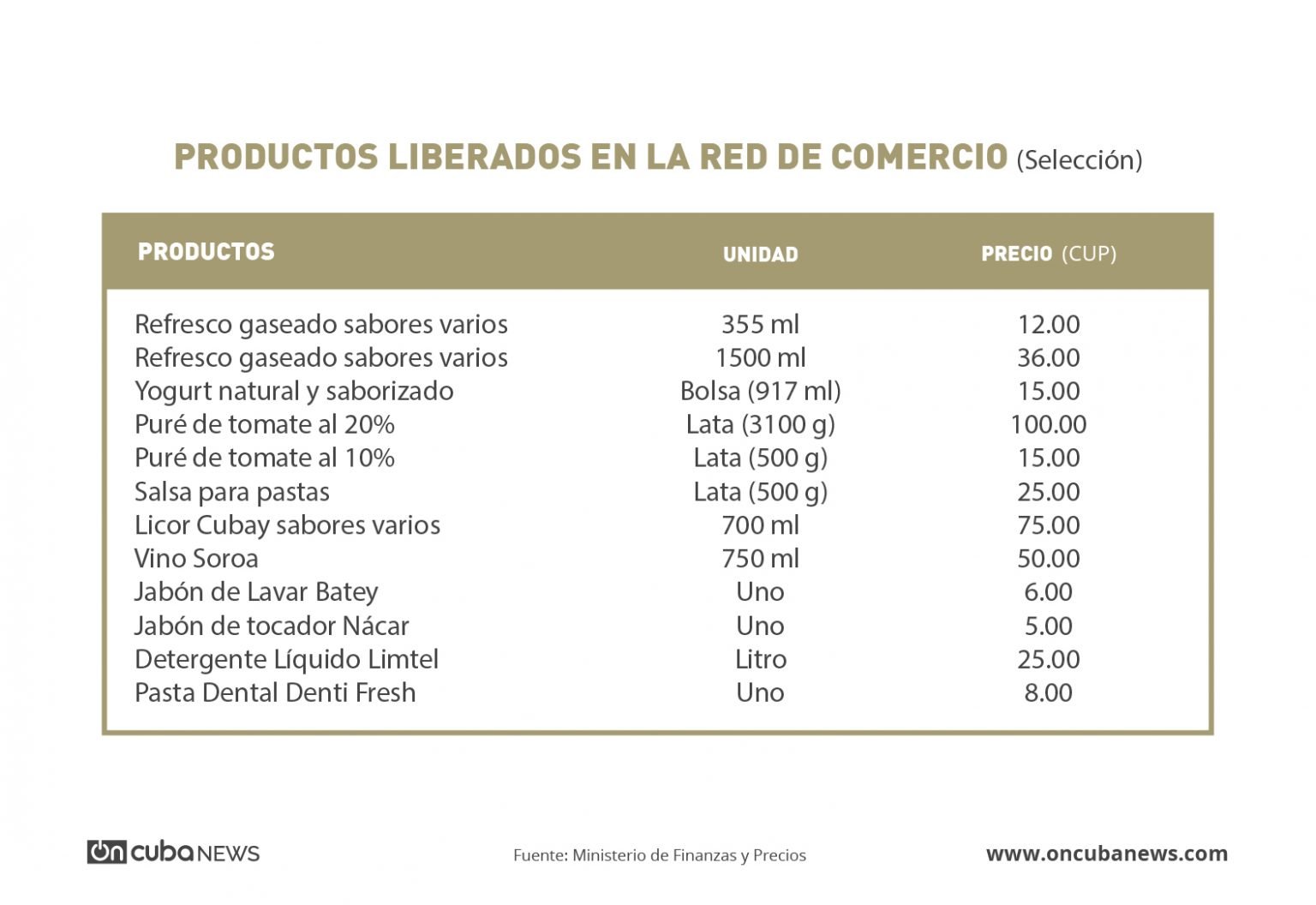

The situation of non-rationed products is different. Government policy has been aimed at reorganizing and unifying their prices, in not a few disparate cases before the monetary reorganization, depending on where and who sold them. In addition, as these are not mainly or fully subsidized products—except for some corresponding to special programs for sick people and for newborns’ products—their state retail prices have been maintained in many of them, even though the authorities have said they may undergo changes in correspondence with fluctuations in the international market.

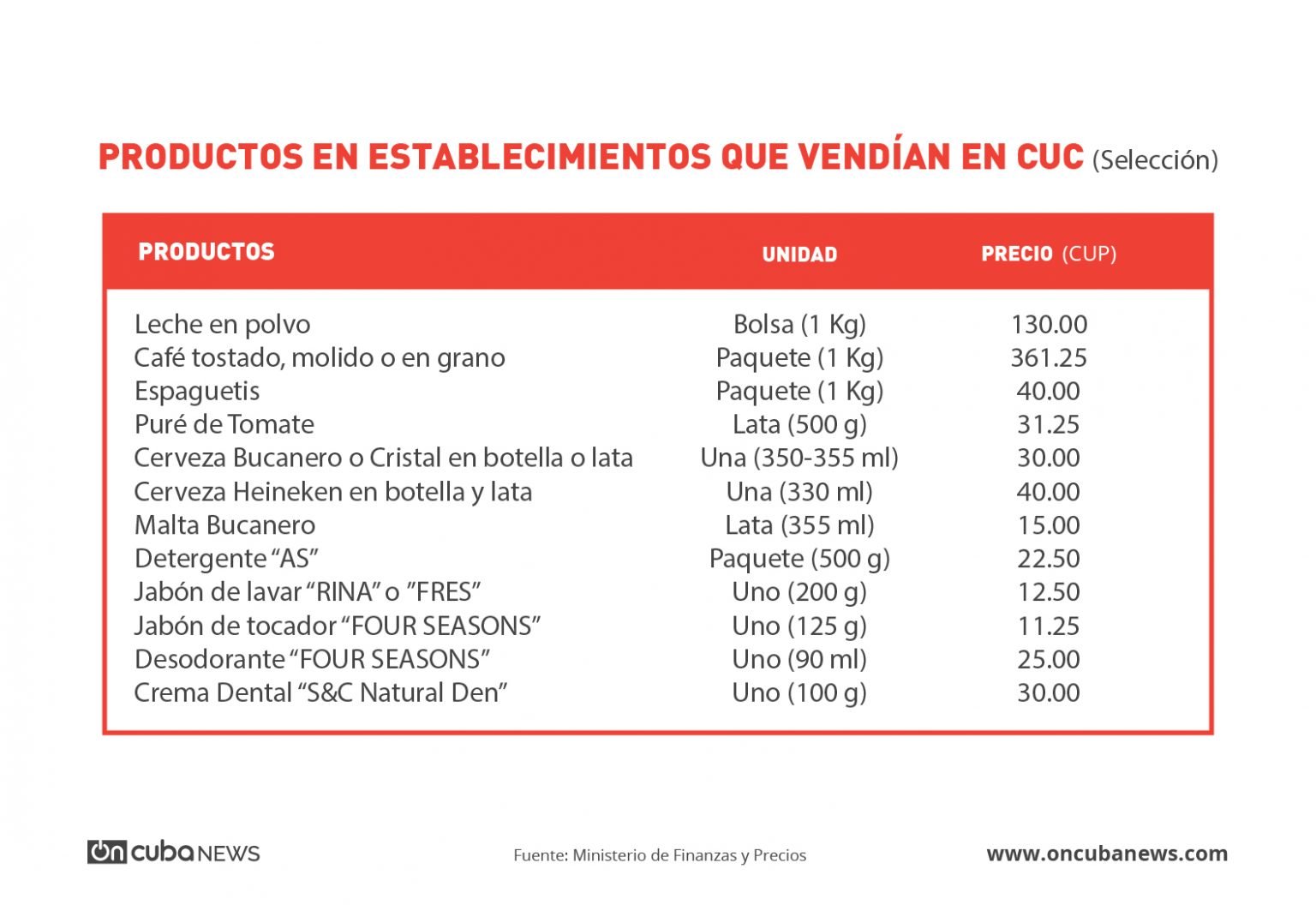

This group of non-rationed products includes food, cleaning, industrial products and even construction materials, many of them in high demand and, at the same time, with a deficit in the state’s network of stores, which multiplies the queues wherever they are sold and also their value on the black market. Bread, chicken, sausage, yogurt, tomato puree, detergent and toothpaste are among the most sought after among those that have centrally maintained their prices, while others such as national rums and beers, and fruit preserves and vegetables, have undergone changes, and not downward precisely.

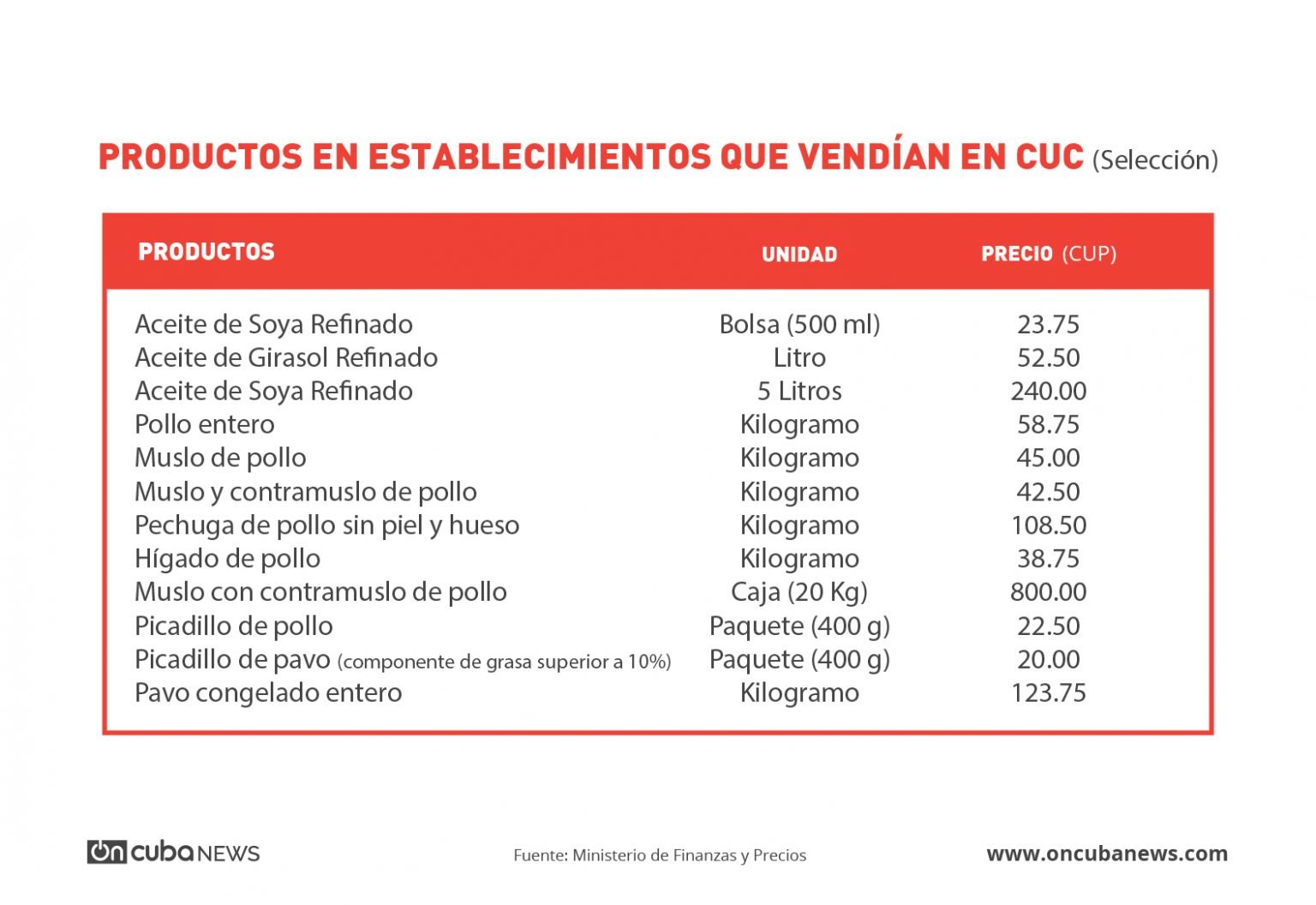

In the specific case of the establishments that until December sold in the already disused convertible peso (CUC)―and of which only a part has continued to accept this currency until the six months established for its final collection have concluded―, their prices have generally remained in the same range, according to the official exchange rate of 1×24. So, however high these prices look today, they are, in essence, the same as before, and they are not a surprise either, since in these stores it was common to pay and also receive the change in CUP, making the conversion between both currencies.

In any case, the main problem with the non-rationed products, no matter the stores where they are sold, are not their official prices but the shortage—be it caused by whatever reason: embargo, corruption, inefficiency—that makes them disappear from the shelves and fatten the coffers of the informal market, in a spiral that, even more so in times of economic crisis and COVID-19, the government cannot contain. In practice, this spiral is a hard blow to the real purchasing power of the new wages, even though they have increased on the island, and, beyond the will or the state voluntarism, keeps the pyramid upside down.

As for the stores in freely convertible currency, opened by the government as a collection mechanism to alleviate the foreign exchange deficit suffered by the island, their prices continue to be unattainable for a large part of Cubans—despite the long queues they also feature—, but these prices don’t seem to have changed with the reorganization, nor the logical aspects—or the illogical, depending on how you look at it—followed for their conformation, so for now we leave them out of the selection that we include in this work. Theirs, as a popular Cuban comedy program assures, is another story.

* For more information, you can consult the Gaceta Oficial No.71 Extraordinary of December 10, 2020 that includes, along with other topics and prices ―including those of medicines that were later be modified―, the retail prices of a group of products being marketed through the domestic network of commercial establishments, products from special programs (subsidized) and from stores that sold in convertible pesos (CUC).