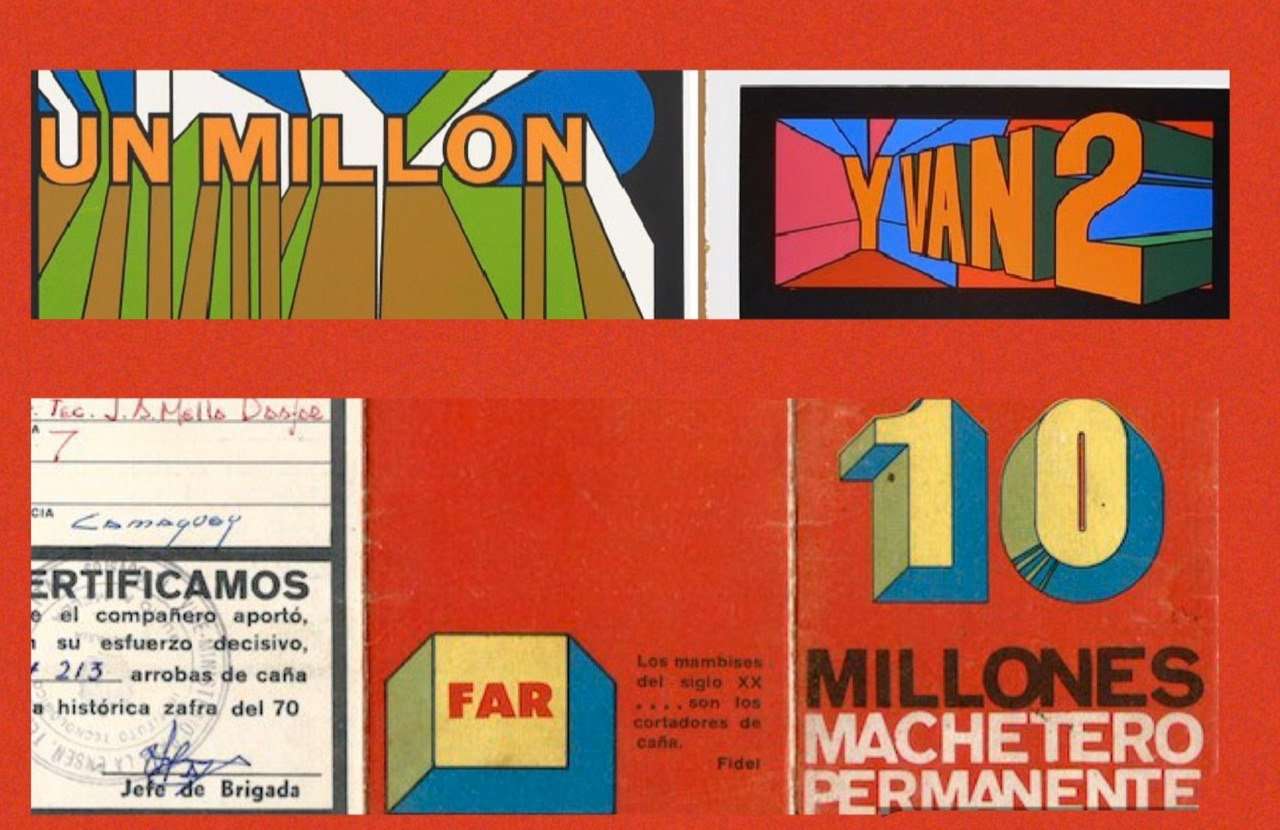

Fidel Castro’s speech on July 26, 1970 in the Plaza announcing the failure of the Ten Million Sugar Harvest would, in fact, constitute the end of the so-called heroic period of the Cuban Revolution (1959-1970). A heresy, indeed, but one that produced a dire economy with high rates of unproductivity, inefficiency and labor absenteeism, all elements that would end up plunging the country into serious problems. The project had accumulated two setbacks in a row: the Cordón de La Habana (1967) and the Revolutionary Offensive (1968). And now, at the very beginning of the new decade, the Great Harvest was added to that list, which was set to be “the great leap forward.”

Starting in the 1970s, a new term appeared in the national idiolect: “institutionalization,” a word with which it was decided to baptize 1977. It was a process of homologation with the Soviets and the so-called real socialism, beginning with the adoption of the management and centralized planning system of the economy, in force until today. It was a move characterized, among other things, by the following:

- Cuba’s becoming a member of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA, 1972).

- Five-yearly congresses of the Communist Party of Cuba (with temporary ups and downs since 1975).

- Creation of the organs of people’s power and the National Assembly (1975).

- Adoption of a new Constitution (1976).

- New political-administrative division (15 provinces and a special municipality, 1976).

In terms of education, during institutionalization, the History of Cuba disappeared from the study plans and was replaced by that of the Workers and Communist Movement. It was a swing of the pendulum: socialism was then located at the antipodes of what José Carlos Mariátegui established; that is to say, it was a “trace and copy,” not a “heroic creation.”

In the teaching of Philosophy, what Professor Jorge Luis Acanda once called “the Marxist Vulgate” was imposed. Higher level institutions were filled with Afanasievs, Leontievs and Ilienkovs, those same manuals initially rejected for their simplifications and dogmas. After the Philosophy Department and the Pensamiento Crítico magazine were dissolved in 1971, its members were left in the air due to categorical imperatives; so much so that a black speck was applied to them that prevented them from even teaching anything else in university centers or publishing a single line in Cuban publications.

The Sociology career disappeared from the universities once it was anathematized as a bourgeois science. “The sociologist, an endangered species,” answered the young poet Víctor Rodríguez Núñez in El Caimán Barbudo. The School of Letters and Art suddenly ceased to be to become the Faculty of Philology, a category brought from the other side of the Atlantic by the cadres and methodologists of the newly created Ministry of Higher Education, with its scholasticism when evaluating professors and classes, which generated an internal resistance seen in a Quevedoist-inspired poem by Guillermo Rodríguez Rivera, the “Soneto metodológico” (Methodological Sonnet):

Pythagoras did not have planned lessons,

Socrates never wrote a P-1

and the worst, that of the two, neither

divided his talks into three phases.

When Erasmus was a teacher

he didn’t use feedback

and it is very unlikely that Plato

sacked anyone due to non-attendance,

O methodologist! in your magnificence,

forgive past teachers.

Even if they were, poor things, wrong,

methodologist, benevolence:

understand that they were engrossed

in the superfluous things of science.

On the other hand, the social sciences of institutionalization had a major problem: they did not reveal or contradict, they only verified official assumptions, as they did 9,550 kilometers away. In the USSR, doctoral theses began by citing on their first page what was stated regarding the topic selected at the last Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) Congress, which was cut out and pasted. The bibliography used was even ordered not by its strict alphabetical sequence, but by placing Marx, Engels and Lenin first, and then everything else. This had the drawback of placing key figures in Cuban political culture in a surrogate position — for example, José Martí, Julio Antonio Mella, Rubén Martínez Villena and Antonio Guiteras, among many others.

At that time, Sovietizing visions of José Martí proliferated. Despite the resistance of those who could do it, because nothing in life is plane, it was a matter of maintaining that in philosophy the man of the Edad de Oro was a materialist, given that, according to the manuals, materialism was progressive and idealism was the opposite. Later they classified him as a “revolutionary democrat” like Chernichevsky or Bielinsky, he whose core was national and anti-colonial liberation, and not the transition to anywhere, except to a participatory and integrating Republic that he was unable to found due to his premature fall in battle in the fields of Cuba.

In another order of things, the adoption of the so-called scientific atheism as a doctrine implied a militancy of the Union of Young Communists (UJC) particularly involved in the so-called Plans of Preparation for Membership (PPI) of young people outstanding for their educational results and participation in the activities of the Federation of University Students (FEU), which reserved a special place for believers who had managed to pass certain initial filters. They had to be shown that their faith was the remnant of a past that had already been overcome, because religion was “a distorted and fantastic reflection of reality” and, in short, the “opium of the people,” an expression conveniently taken out of context by the manuals and books translated into Spanish and widely used in the national system of the Party Schools, created at that time.

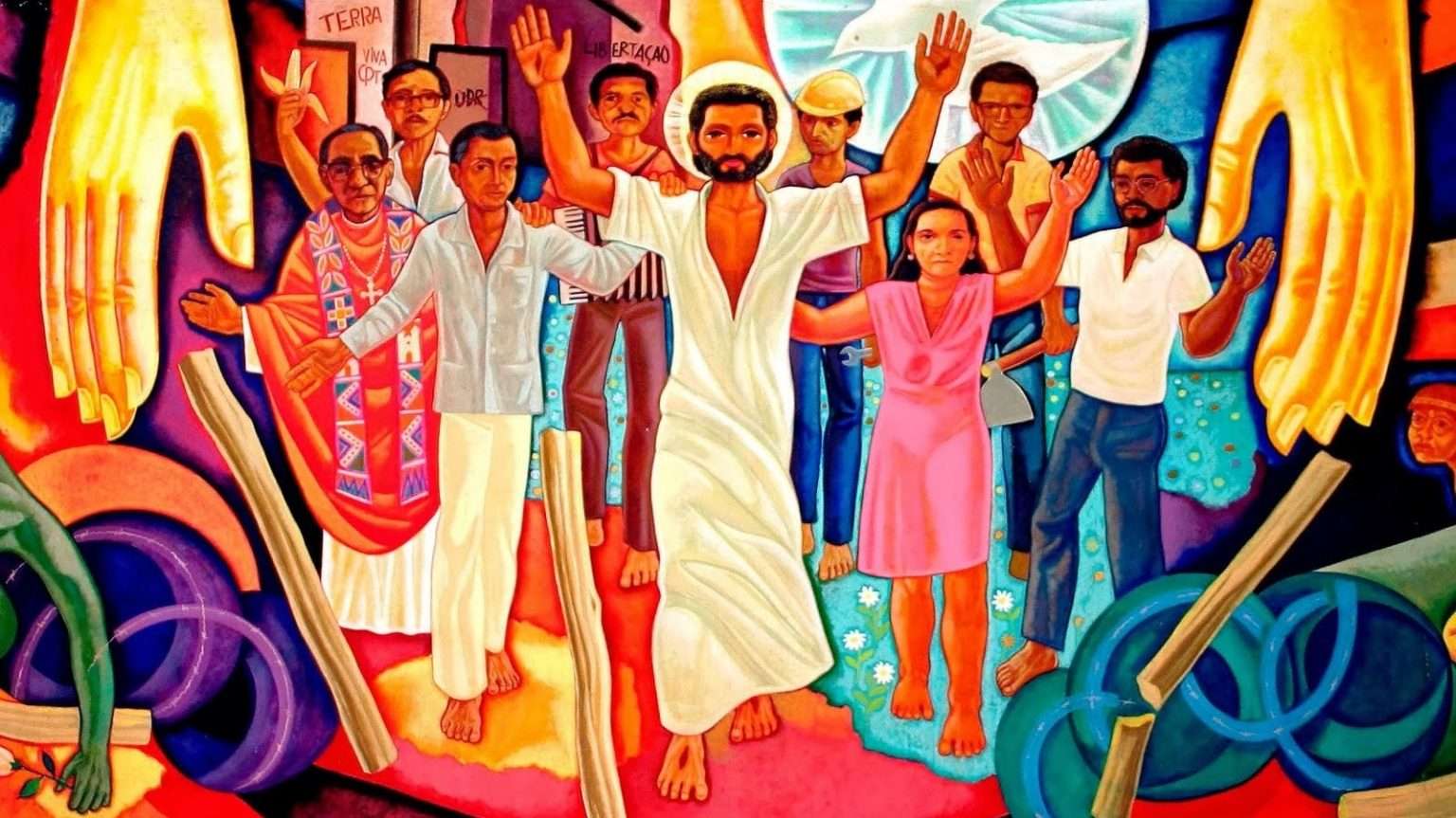

The problem was that atheism, even with that positivist surname, was spreading over the social fabric precisely when Liberation Theology (LT) and the grassroots ecclesial communities were challenging the traditional ways of being a church in Latin America, with the emergence of a popular church and in the context of the Second Vatican Council, which implied the emergence of a new type of Christians that led Fidel Castro, during his visit to Salvador Allende’s Chile, to speak of the “strategic alliance between Christians and Marxists,” a call that did not make any dent in the official line in terms of opening the door to religious people to the ranks of the PCC and the UJC and a fact addressed some time later, in 1985, by Fidel Castro himself in his book of answers to Brazilian Dominican Frei Betto. And what is more: they were not allowed to enter certain university specialties — journalism and philosophy, for example — because they had “ideological problems” that made them incompatible with the scheme. They were given no choice but to enroll in civil, mechanical or electrical engineering, because they were unable to work, once they graduated, in the so-called spheres of social consciousness.

The models that the revolutionary believers discussed with those who would supposedly make them abjure their faith ranged from the Colombian priest-guerrilla Camilo Torres and Frank País — a Baptist murdered in the streets of Santiago de Cuba, National Chief of Action and Sabotage of the 26th of July Movement —, even Father Sardiñas with his olive green cassock from the Sierra Maestra and the Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal. But these data did not even seem to daunt the logic of the indoctrinators, who very often had much less general and political culture to make an in-depth discussion with many Christians who very ahead of them in these and other fields.

Of course, those who maintained “correspondence with foreign countries” also had “ideological problems,” as was inquired in the forms, a question that came from the 1960s and that, moreover, began to enter into a crisis with the first visits from “the Cuban community,” as a result of the 1978 Dialogue and the changes in official policies in that area.

And then came the Gray Period, inaugurated by the National Congress of Education and Culture (1971), which actually lasted well beyond five years. Difference was anathematized, often sending those who wielded it to the other side or ostracized for a variety of reasons ranging from sexual preference to religious belief — or both.

To be continued…