Labels and declarations of principles almost always carry generalizations, summary tendencies and even schematics, which are often exaggerated in this age dominated by tweets, memes and summary statements. Controversy is in full swing. It encompasses dozens of web pages and social networks in Cuba―especially within the community made up of audiovisual creators―to try to clarify the ambiguous content of the term “independent,” a name that serves as an umbrella for those committed to making a personal film, of intimate evocations, as well as those others more concerned with social criticism and nonconformity, or third parties, who seek experimentation in language and narration.

What does Cuban independent cinema consist of, how far does it go and what seems to be its immediate destination? The answers to such questions, very timely regarding the launch of the long-awaited Fund for the Promotion of Cuban Cinema, appear in abundance, and in the midst of enlightening definitions, there appear some that only seek to expose the merits of the opinion-maker, as if it were a tacit competition, to win the title “To the most independent,” or at least, to the least “contaminated” by the institutions, mainly the ICAIC.

In the first place, some have lost sight of the fact that all Cuban cinema, absolutely all, seen from a global perspective, can be considered independent insofar as it is produced and exhibited on the margins of the planetary homogenization imposed by Hollywood and other multinational emporiums. So our films, and the mere fact that there is a national cinema, are linked to the everlasting desire for independence in all our art, history and idiosyncrasies.

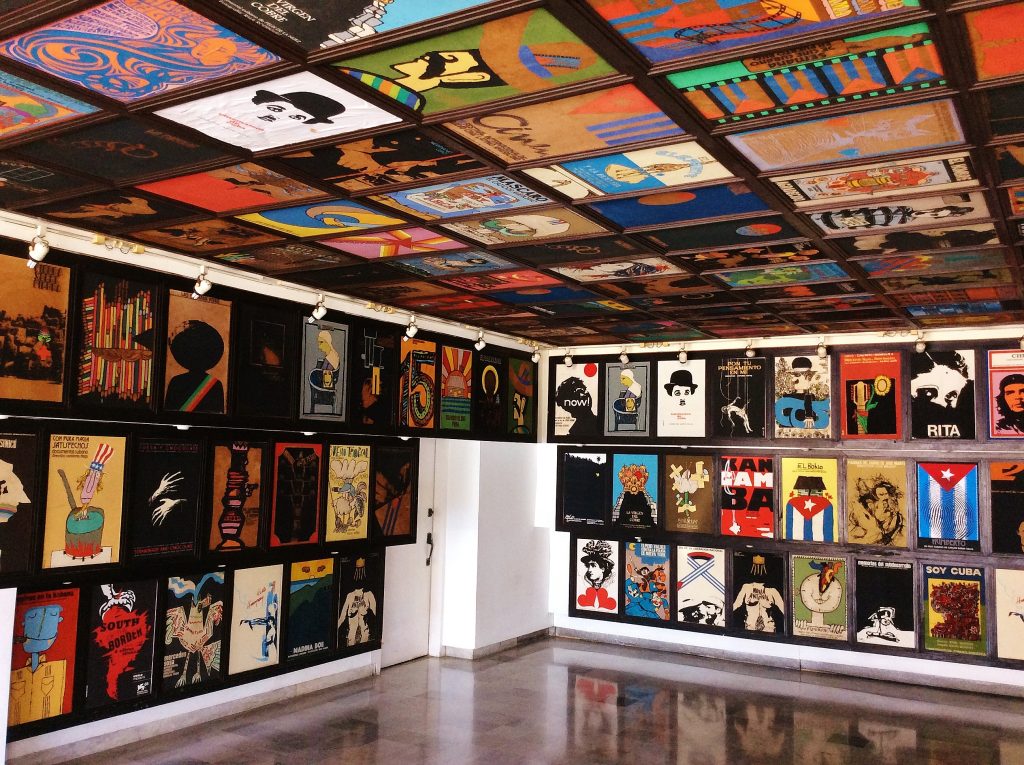

Second, myopia and ignorance would imply overlooking that most of the most emancipatory, complex, beautiful and unique Cuban films of all time were produced by that same ICAIC from which some reinventors of autonomy try to distance themselves. Because if Memories of Underdevelopment and Coffea Arabiga and Vampiros en La Habana were produced by the ICAIC, if Mosfilm supported the best films by Andrei Tarkovsky, if Andrzej Wajda and Zhang Yimou were always on the official filmmakers’ lists, if Vertigo and Citizen Kane were generated thanks to the good offices of Paramount and RKO, respectively…then the question of artistic autonomy should never be reduced to the affirmation or denial of collaboration with official institutions.

Third, the best way to forever lose the independent character of a work can be associated with the fact that its filmmakers become hostages to the obsession for independence, because all filmmaking is an act of collective creation, and therefore involves negotiations, agreements, dependencies, and the emancipatory essence can be sustained, through thick and thin, as long as the essential spirit of the creators is sustained, distanced from the agendas for or against promulgated by one or another faction. Because, from that point of view, we could consider the non plus ultra of independence of the works and filmmakers who protest, denounce, or suffer censorship, as if the critical virulence attached some safe-conduct to access the Parnassus of the uncontaminated martyrs.

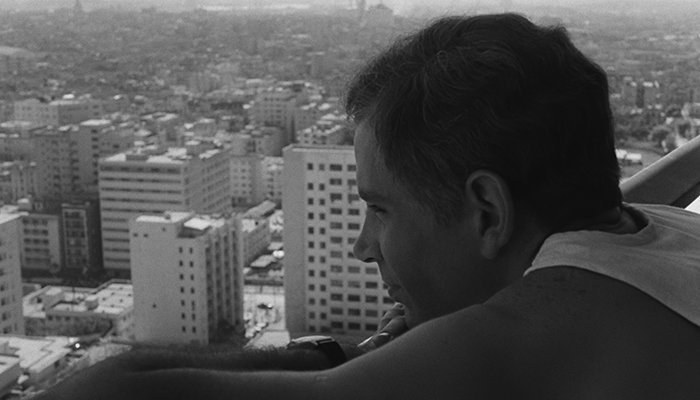

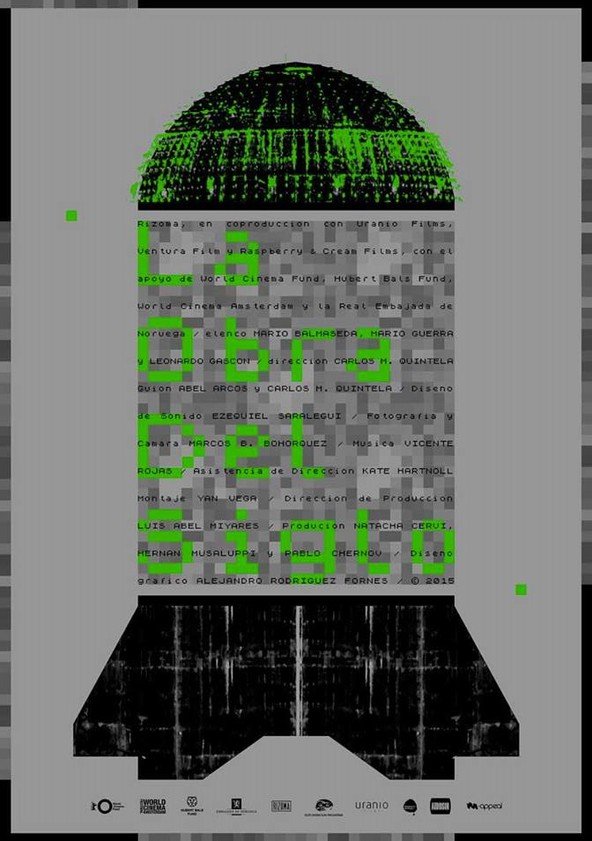

The bitterness of the discussion comes, I believe, from the different ways of conceiving the independence of creators, and furthermore, some try to confirm their leadership based on the insistence on the questioning and political vocation of independent art, and even accuse of opportunism, naivety or cowardice those who try to achieve an aesthetically valid work, and of sovereign essence, within the Cuban institutional framework. They want to ignore, or need to ignore, that to define the Cuban cinema of the 21st century it is necessary both the innovative appropriation of imperfect and experimental cinema a la Miguel Coyula in Memorias del desarrollo (2011) or Carlos Quintela in La obra del siglo (2015) and of linear narrative, professionalism and generic borders present in José Martí, el ojo del canario (2010, Fernando Pérez), La película de Ana (2012, Daniel Díaz Torres) or Conducta (2014, Ernesto Daranas).

Considerably representative of the liberation with respect to the hindrances imposed by the official stories, in their desire to reread serious moments of the recent past, were Santa y Andrés (2016, Carlos Lechuga), El acompañante (2016, Pável Giroud) and Un traductor (2018, Barriuso brothers) cardinal also in terms of witnessing the rugged relief of an independent cinema that is committed to the review of social and political circumstances, based on the intellectual honesty since the filmmakers-scriptwriters deliver their personal truth, in close contact with the national reality that happened beyond the television newscast.

Y si Venecia (2014, Enrique “Kiki” Álvarez) could be conceptualized as the typical Cuban independent production, because of the way it was made, its taste for improvisation and its visual acquiescence to a certain dirty realism, three years before Juan de los Muertos (2011, Alejandro Brugués) sailed among us, and in all parts of the world, like a flagship of an autonomous Cuban cinema, of countercultural essence, but installing in budgets and packaging that seemed unattainable for the island’s cinema, including that of the ICAIC.

Because accepting that independence depends on the budget, or on the absence or presence of an official sponsorship, is equivalent to trying to revalidate in Cuba the operation of the very different U.S. industry: you are independent and you are competing in the Sundance Film Festival, or other off circuits, while your budget is below a million dollars (to say a figure), and you stop being it when producers and distributors that inflate costs are involved. According to this reasoning, La pared de las palabras would be more independent than Suite Habana, both by Fernando Pérez, only because the first was made outside the ICAIC. So, the strictly economic approach, to assess autonomies, seems to me completely inadequate.

The praxis of cultural industries has shown that independence can adopt various packaging and essences, because it should not be forgotten that the list of “dependents,” aligned with a certain ideology and institutionality, includes names that define artistic sovereignty such as those of Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, David Lean, Michael Curtiz, Fernando Solanas or Leni Riefenstahl. Because the beauty and quality of some essential classics, made by Santiago Álvarez, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Humberto Solás, Sara Gómez or Nicolasito Guillén Landrián is also associated, let us recognize it once and for all, to official cinema, made thanks to institutions ready to culturally illustrate the changing faces of the nation.

To deny the emphaticness of the axiom that the beauty and quality, and even the social shocks, that a film can cause have nothing to do, neither in Cuba nor in other countries, with the hazards and negotiations of its production, not even with the ideology of its director is simply a collateral effect of ignorance, or of the concrete and visible effort to sabotage the ICAIC Development Fund. Thus, some try to impose on the film community certain personal, selfish and interested agendas, which superficially manipulate the rhetoric linked to the always attractive principles of the emancipatory and countercultural.

Because the authenticity of the filmography cultivated by stubborn fans of emancipation such as Jorge Molina and Juan Carlos Cremata or Alejandro Alonso and Rafael Ramírez, in addition to others mentioned above, escapes any formula or schematics, and in this lies their honor and prize. It doesn’t matter if their films were produced by ICAIC, EICTV, ICRT or FAMCA, through crowfunding, or through the Hubert Bals Fund or the Norwegian Embassy. No matter how much one tries to argue otherwise, from Havana or from Miami, none of these production companies managed to establish a monolithic thematic discourse, much less a univocal style, linked to political orthodoxy. The list of nonconforming works, in one sense or another, is so long that the task of imagining it overwhelms me.

Thus, the controversy about independent cinema and its cultivators must lose that occasional air in the style of reggaeton artists. I think it is better to take advantage of the distance to keep imagining the next works, writing them, thinking about the shooting and editing and post-production. Meanwhile, it is necessary to apply to any fund or mode of financing that could guarantee the completion of the work, because Cuban cinema will live on its finished films, and that the public, large or small, can access them.

Each person will deal with the ethics of artistic autonomy, as their conscience and their circumstances or aspirations indicate, and none of these decisions is publicly debatable, because controversies on social networks can oil thought, but they never manage to illustrate the imprecise and fascinating image of a nation in the process of definitions. That’s what good movies are for, independent or dependent.

Click here to listen to this and other podcasts of the OnCuba Digital Channel on the Ivoox platform.

Joel del Río is a journalist, art critic and professor. He works as a journalist at the ICAIC and at the International School of Cinema and Television of Cuba, in San Antonio de los Baños, where he also teaches workshops on cinematographic genres and the History of Latin American Cinema.