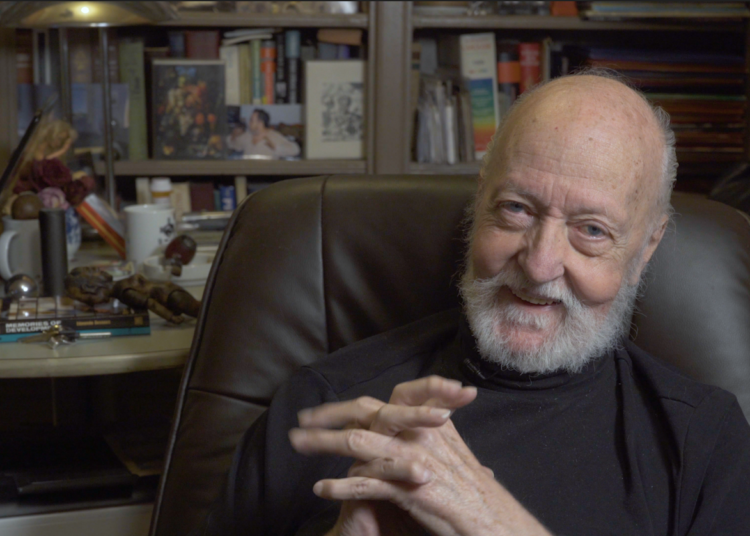

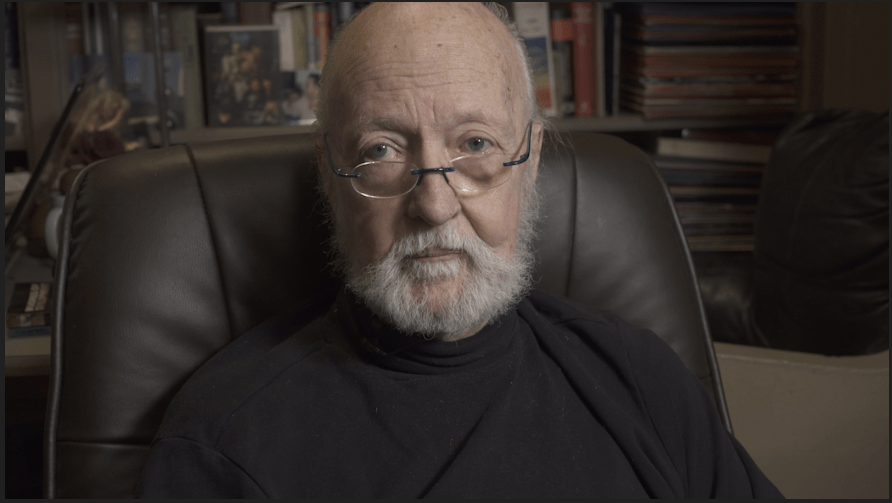

A video conference from Vedado to Upper West Side in New York took us to Edmundo Desnoes’ living room. At 88, he celebrated the technology that was allowing us to talk: “everybody criticizes it. They say one loses with it…, well I believe one gains. Every cloud had a silver lining. Reality always has two edges: an edge that cuts and an edge that cures.”

Lezama told Juan Edmundo Pérez Desnoes that the magazine Orígenes would not publish a Pérez, and that’s how his signature came about. “There’s where the Desnoes came in. When I want to get lost among the people I’m Juan Pérez again.”

As a child he spoke Spanish with his Cuban father and English with his American mother. I was “the son of the American, and that gave me that bicultural question between the United States and Cuba.”

“Even today relations between the Cubans from the island and the Cubans of the exile should be closer,” he says. “Cuba is a tree that has its roots on the island and the branches and leafs subject to all the accidents of the time.”

It’s been 50 years around these days that Memories of Underdevelopment (Tomás Gutiérrez Alea) was premiered. It took to cinema the novel by the same name published three years before by Edmundo Desnoes. The question that tormented Sergio Carmona, the bourgeois stranded in the middle of a social process that he was trying to understand, persists: “How does one get rid underdevelopment?”

What were the 1960s in terms of culture in Cuba?

They were intense because we became the center of world attention. My novel gives a vision of Cuba, and through the character one entered into the process of the first 20 years…. Everyone visited us: they made us feel important.

I say that the success of Memories… is due to three things: the Revolution, the moment of French cinema’s new wave and the acting of Sergio Corrieri, who is, I would say, the Mastroianni of the poor.

Success always greatly depends on the historic circumstance.

What is the writer’s place in society?

The writer must create an ambiguity to be able to say what he really feels. Not to belong, but neither to totally alienate himself. For the writer it is fundamental to survive. He must be society’s conscience.

I started off wanting to be a painter. I studied painting, but it seemed very complicated, because of the easel, the brushes, and actually for me it seemed like manual labor. So I thought that writing was easier; although I have always had an intimate relationship with visual arts.

I also became a writer because as a child and as a young man I couldn’t sing, but I did learn the lyrics of all the songs.

Why is subjectivity important in development?

We have to think in terms of global culture. There’s an essay by Auerbach where he compares Don Quixote to Hamlet. Global culture has gone more along the path of Hamlet – doubt – than along that of Don Quixote, which is: what you believe is reality; what you imagine is real, you don’t question it, there is no doubt. And without doubt progress cannot be made. It could be that with that fanaticism it is possible to conquer. The Spaniard unquestionably conquered, based on initiative. But doubt is fundamental in the modern world.

Actually, the most intimate relationship we have is when we speak with ourselves. We live in a very intense internal dialogue. And when there isn’t subjectivity and everything is simply the surface, it’s a limitation. I greatly question the entire world of magic realism, which is the psychological base of folklore, the magic thought. I believe that one of our problems is trusting too much.

How do you identify with Sergio in Memories of Underdevelopment and the character of Edmundo in Memories of Development?

I believe that true realism is the mixture of what you have lived with what you have thought you could live. Both characters are a mixture of what I am with what I imagine I could have been. For example, in the case of Sergio, he is the other I. If I hadn’t become integrated to the Revolution, I would have probably been Sergio the observer, who is outside, but at the same time is part and analyzes. I could have been that character. It’s another aspect of our identity: what we would have wanted or could have been is also a schism of what we are.

In the novel it says “That is one of the signs of underdevelopment: inability to link things…. The environment is very bland; all the talent of Cubans is spent on adapting to the moment. People are not consistent. And they always need for someone to think for them.” A few years ago Titón spoke about when this would not exist, the aged film. How far is Cuba today from your novel? Did Memories… grow old?

It’s not for me to say that because I’m not in Cuba. But according to what I hear, what the people who write to me say, for many Cubans Memories… continues being an expression of what they have lived; it has not turned into a sterile past. Juan Ramón Jiménez used to say that the classical is what is alive, then Memories… is a classic because the book and the film are alive.

Cuba is still underdeveloped. I believe that is an eternal sentence. But well, we made an effort, the Revolution was a great promise, a dream, but Borges used to say that defeat has a dignity that the noisy victory doesn’t deserve. And we have to celebrate the defeat of having tried something huge and having failed.

Cuba’s existential center, which was music, is lived in the present, and the Revolution asked for people to make sacrifices for the future. That element of Cubans of living in the present, and that they be demanded a sacrifice for the future, and in the end to see that all that sacrifice did not bring economic wellbeing, leads to thinking that it is preferable to sing and dance.

Cubans relate so that when something becomes intense, someone makes a joke and the tension disappears. Cubans always do away with tension and recover the balance. That allows them to evade antagonism.

What did you feel on December 17, 2014 when the change of policy between Cuba and the United States was announced?

I was here, I wasn’t in Cuba. But I believe that was a great moment of reconciliation, a promise. There’s a phrase by Ortega that says that nothing resembles more the embrace than the hand-to-hand struggle. And what happened between Cuba and the United States is an embrace, and it is a struggle. We have those two aspects, the proximity and the amount of Cubans who live in the United States make it an embrace and that it be a struggle. At the time there was the opportunity of increasing relations. I believe it is fundamental that those two groups integrate to create a more powerful nation and culture, if not it becomes an antagonistic thing that is negative.

Despite the aggressiveness between Cuba and the United States, Americans visit Cuba and are treated as brothers and sisters. There is political enmity, but it is not centered on the individual. I believe that the reconciliation that began in the Obama era would have facilitated a greater rapprochement, where Cuba is already totally affirmed as something independent in relations with the United States. That becomes frustrated when Trump closes.

Do you feel more Latin American or more Anglo-Saxon, or you don’t define yourself as none of the two?

I would like to define myself as both! I would like to join Don Quixote and Hamlet, to create a combination of doubt and that Spanish sensitivity. I am that mixture: the dream of Don Quixote’s crazy things with Hamlet’s doubts.