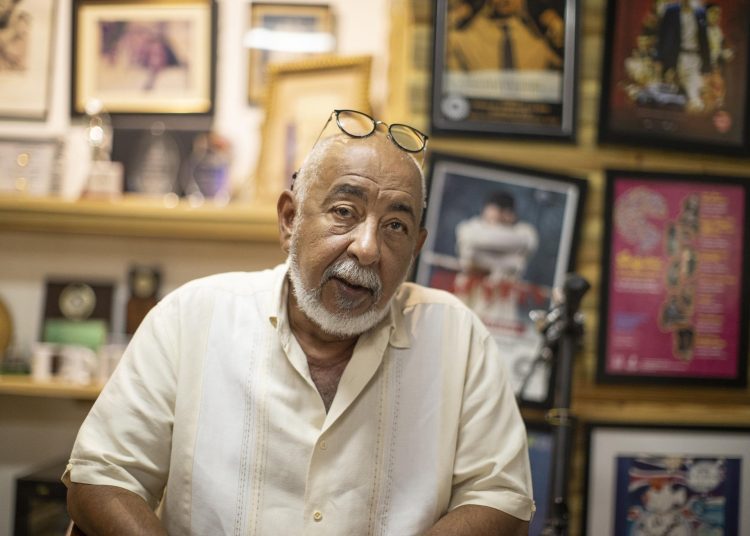

In Cuba “we’ve hit rock bottom,” “we are experiencing one of the deepest crises”; and more than food or electricity, “what is most lacking is hope,” affirms the writer Leonardo Padura, a chronicler of the Cuban social reality through his work.

“It’s like another crest of a long crisis.… We’ve hit rock bottom and the worst thing is that, if at other times there was still some hope that things were going to improve, I believe that what is most lacking today is not food, fuel, electricity or coffee, what is most lacking is hope,” says Padura in Santo Domingo, where he is meeting to present the reprint of his book Los rostros de la salsa and to give workshops to young people.

https://twitter.com/UNESCOHabana/status/1683513902133379072?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1683513902133379072%7Ctwgr%5E609efb269c93d5cd9599bc53e585dd72a8ed0ee8%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Foncubanews.1eye.us%2Fcultura%2Fliteratura%2Fpadura-en-cuba-hemos-tocado-fondo%2F

A Cuba where “control and fear is an industry that does work,” as demonstrated by the repression of the 2021 protests, which “was an explosion, a scream that Cuban society gave and the only thing that happened was that the controls and repression mechanisms became more acute, intensified…. It has also served to let people know that if they go out and break a window, they can go to jail for five, seven, ten years,” he said.

Writing bypassing censorship

Padura says that it is not easy to write in Cuba, but acknowledges that his situation is very different from that of other authors. His books come directly from his computer to his publishers in Barcelona, which is a “great advantage”: “It guarantees publication and that my book will not go through any filter of Cuban institutional censorship.”

In addition to censorship, in Cuba there is self-censorship, a “defense mechanism,” in his opinion, even “more humiliating, an exercise in personal castration,” he told journalist Almudena Casado.

But authors look for alternatives to write and publish, with strategies in the style of Carlos Saura’s first films, “full of metaphors and symbols,” or looking for publishers in Spain, Mexico, Argentina and Colombia.

At this time “it is almost impossible for a normal writer to publish, unless it is a political propaganda book that has the support of some instances,” says this author, who has accumulated awards such as the Princess of Asturias Award for Literature, the Cuba’s National Literature Award and the Order of Arts and Letters in France.

Chronicler of the Cuban social reality

For many, Padura’s work will serve as a newspaper library in the future to find out what the Cuban reality has been like. “I have done this exercise unconsciously at first and then I have realized that it was a requirement of that literature itself, to make a kind of chronicle of contemporary Cuban life,” he explains.

But this journalist has tried to ensure that his chronicle does not have a political character so that “it does not lose the support on which it was written” if the situation changes and he has preferred to elaborate it “from the social and human point of view of the personal traumas that these situations create” in Cuba.

“The powers try to erase from the past the moments that are inconvenient and only keep those that in some way reaffirm their position…. That is the reality of a totalitarian system,” he stresses.

Faced with this, Padura tries to preserve social reality through his main character and protagonist of his detective series, Mario Conde: “I think that in a few years the vision of Cuba that is in those novels will be much closer to what has been the reality than what the Cuban newspapers have expressed.”

The passage of time

And in this period that Mario Conde goes through in the novels, from 1989 to 2016, both this character and Padura himself are not the same, “the passage of time inevitably changes people.”

Mario Conde has evolved, “he has definitely become more pessimistic, with more aftertastes, with more intention to preserve memory.”

Through Conde, Padura, who reveals that he has an idea for a new novel with some notes, analyzes the aging process itself, since “it is inevitable that, as time passes and we have more of the past than the future, in some way we become a bit conservative and more cautious, but at the same time we lose fear.”

“My mother (she is 95 years old) repeats a Spanish phrase ‘For the years I have left to live, I don’t give a damn about anything.’ As the years go by, she realizes that for the years she has left to live, she doesn’t give a damn about anything. You have to not give a damn about many things and I have learned that over the years,” he concludes.

EFE/OnCuba