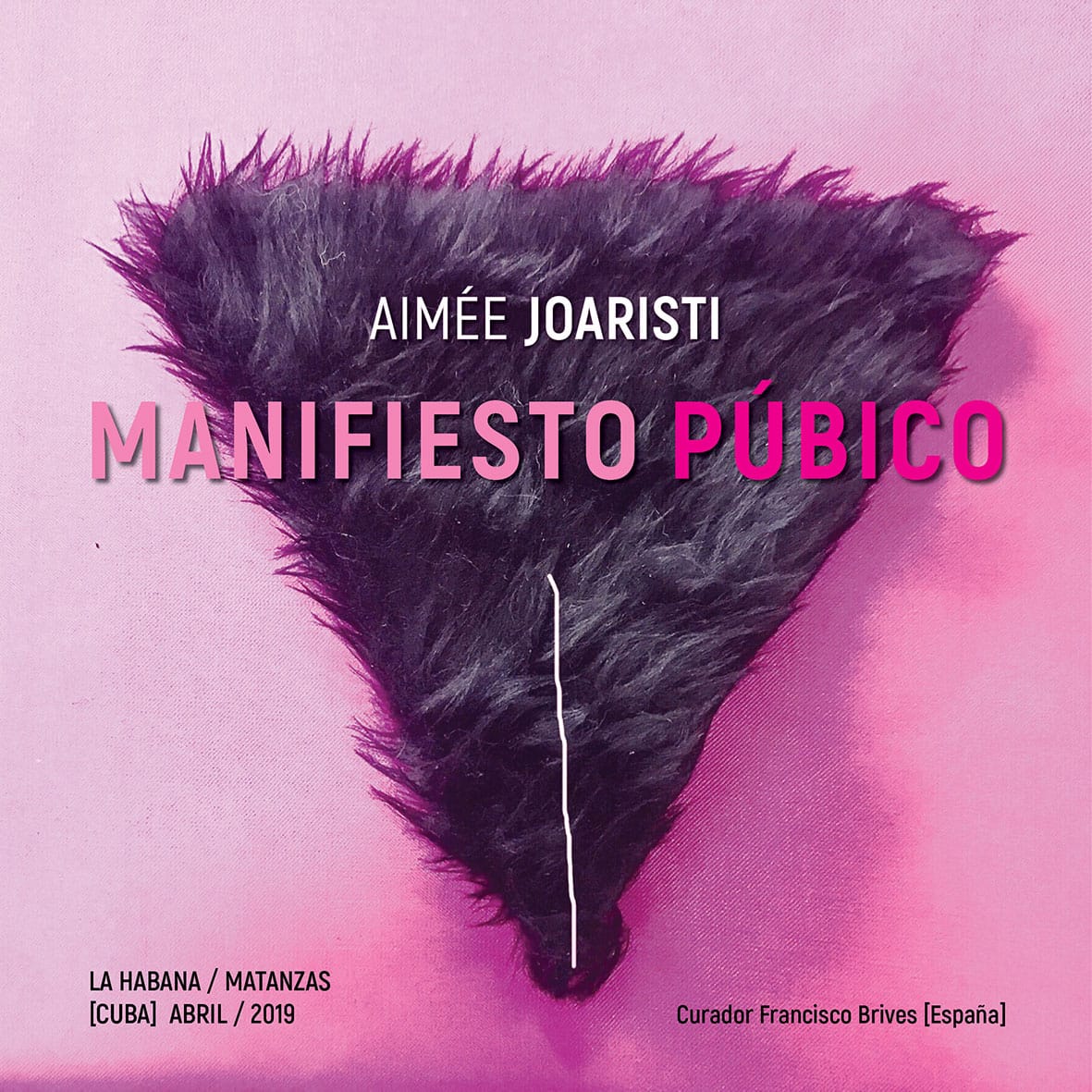

The first time I heard of Aimée Joaristi’s work was through photographer Ernesto Granado, who had documented Joaristi’s passage through the 13th Havana Biennial. My colleague, a man of the world, was, however, a bit dislocated with the almost clandestine intervention of the artist in the city. According to what he told me, “hairy triangles,” which represent female pubes, had been “installed” in different columns of the Cuban capital, within easy reach of the curious, who could take them home without knowing what it was about. Through the piece, the artist transgressed, and the passers-by felt that they were also transgressing by taking something that they had not acquired in a lawful way.

Aimée had been invited to the Biennial with the installation Enrollate conmigo, for the curatorial space “Detrás del Muro.” The piece consisted of five rolls of canvas 1.5 meters wide and between 20 and 15 meters long, which slid down the façade of a building facing the sea, on the Havana seaside walk. Part of the work was the performance of the opening day of the Biennial, when the artist cut segments from the scroll entitled “La ofrenda” (acrylic inlaid with plastic roses) to give them to the public.

Manifiesto Púb(l)ico (MP) (Pub(l)ic Manifesto) was a kind of unauthorized bonus track of Aimee’s participation in this event, one of the most important of the visual arts on a continental scale, which is held, sometimes with irregular periodicity, in Havana, which is also the artist’s city of birth.

Since that participation in the Biennial, I have searched for information about Aimée, and I learned that she graduated from Interior Architecture in Madrid, and did a second career at the prestigious Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in New York City.

I also learned that she, so far, has made nine personal exhibitions, among which it is worth noting Tres Cruces, Museo C.A.V, La Neomudejar, Madrid, Spain, 2018; XMetro, White Concepts Gallery, Berlin, Germany, 2017; Escindida, Galería Gorría, Havana, Cuba, 2017, and Silencios y gritos, Klaus Steinmetz Contemporary, San José, Costa Rica, 2015.

In 2020 Aimée won the Artist of the Future Award, granted by the U.S. Contemporary Art Curator Magazine.

I recently had a talk with the artist in which we talked about her art and the place Cuba has in her creation. Here it goes.

What place does Cuba occupy in the construction of your identity, which has been forged in different cities of the world?

Cuba occupies a rather incorporeal place in my imagination, with imperceptible physical connotations, since I left the country in 1959, when I was only two and a half years old, and did not return until 1999, when I consciously set foot on the island’s soil. And I felt what it represented

The first impression I had of the city of Havana was to find myself in a Seville located in the tropics. With this sudden conception, I tried to bring together my two existential worlds: Spain, where I was raised, and Cuba, where I was born.

As is logical, in my mental construction there are very different fetishes that denote Cubanness: the congrí, the black beans, Miramar, Lucumí, pork, the Castro surname….

Havana is for me a small Spain. In it my present and past life converge. I come, on my father’s side, from a family of Basque migrants. My grandfather, upon settling in Cuba, founded a steel structures company with limited resources that became important over time. My mother descends from a wealthy sugar industry Cuban family. The cultural contrasts that occurred in my life have enriched my way of facing everyday life, that is why the fables of princes and beggars always exist in my mind.

How did the transition from architect to artist operate in you?

Art has been the lung of my existence. It’s why I breathe and function. I cannot separate it from my life, nor can I accurately deduce where the limits of each practice or condition begin and end.

I studied interior architecture by default in Spain. The specialty was easy for me, and since I also liked to have fun, I didn’t have to be locked up for hours studying. My time in New York was a carefree time of fun and study. There I also enrolled in advertising design courses, another manifestation that came naturally to me, and did not hinder too much my desire to live intensely. From New York I went to live in Milan. In that city I worked in the world of ready-to-wear fashion and developed as an interior designer; this motivated me, a few years later, to open my own architecture and interior design studio in Costa Rica.

My dilettante life came to an end when I found success in that profession. For many years I felt that I was getting paid to have fun producing high-end projects. But when the world economic crisis of 2008 arrived, that existential feeling of wanting to start again gained strength; I decided to take a sharp turn of the wheel and dedicate myself almost entirely to art.

Reviewing the resume that I was able to access, I see that your work is made up of series. Is this a conscious act based on the very genesis or do you accumulate works that you later discover are articulated in a common discourse?

My creative production methodology is born of instinct and is nourished by it. Unconsciously I work in series; and not for a preconceived reason, but because they are all daughters of the same momentary feeling, which does not end with a single work or with a group of them. Obviously, there are bridges between one series and the next. I am referring to works that are on the way, that dialogue with the past and the future; that on their own transit reveal some supposed dissociation or loss of belonging, but that then time takes care of relocating.

Describe the journey from idea to work.

Many times the work is born before the idea, and it takes me a few days to realize that a project has been born. My ideas are clarified in the early morning hours, they take shape, to then be able to materialize them. As I work on the surface and always attested by basic instincts, there is a common thread that becomes much more obvious in the final reading of the spectator, or when later I distance myself and broaden the analytical perspective of my work.

I work for continuous and intense periods, until I reach physical exhaustion. That is why I practice yoga and meditation, as well as other sports disciplines that keep my body strong and agile. This training is also necessary to be able to create large-format works, a dimensional aspect that I am passionate about to the absurd.

I imagine a future time in which, sitting calmly and almost tied up, I dedicate myself to creating a miniscule work until I disappear….

You are a very powerful installation artist. Also your “easel works” denote an intuitive, gestural, carefree expressiveness that somewhat contradicts your training as an architect, based on the assumption that architecture requires, above all, functionality and rationality. Do you feel that contradiction?

The type of pictorial work that I develop goes from floor to wall at a meteoric speed. I never know where to start: painting on a bench or running around looking for the canvas. Normally the same work passes both through the floor and through the wall, and from the wall to the floor; sometimes I even leave it out in the open for a while so that its process can continue without my intervention.

Since architecture is a fairly indoctrinated, academic practice, and not in my nature, the leap into the world of art was a kind of liberation from the desk, from formal methodological structures. Freeing myself from the whims of others and taking on the challenge without strings attached made me realize that this new stage was even more difficult and complex. I was on my own without excuses, no third parties, no markets, no customers; faced exclusively with a personal catharsis.

Design is also a service activity, with a high degree of rationality in its processes. Neither architecture nor design are, from my point of view, sufficiently viable manifestations to fully experience this need for artistic catharsis.

The urban intervention Pub(l)ic Manifesto began its journey in Havana. Then it has been seen in Tokyo, Madrid, Venice, South Africa, Miami and Costa Rica. According to the results that you have collected at the level of the spectators, is your purpose of mobilizing consciousness towards the issue of gender inequality fulfilled?

The greater purpose, which is that of gender equality, is not being fulfilled, and we are still very far from one day its being fulfilled, but as far as I am concerned, it is a grain of sand in the construction of the ideal. Sometimes ideas that emerge in a harmless and almost fortuitous way become unsuspected banners. The very fact of using a female pubis or vagina, so ignored in the social and cultural environment, not only dismantles the stigma and cancels the eroticism of the symbol, but also points to the conflict over the regulations in which we live, in which the male and his weapon, the penis, continue to beat us.

Sedimentations like this, sometimes manifested even in small gestures, have acted as subtle elements that condition our cultural identity. Pub(l)ic Manifesto is a small subversive act against that reality; a questioning of everything that makes you feel guilty.

Can you relate some notable differences in the reception of MP by residents of different cities?

The country that has had the best reception of the work on an expressive level has been Cuba, for being extremely sexist; for having a society where sex, or as people vulgarly say on the street, “screw,” is paid special attention and given priority in the absence of other freedoms. That is why the MP object caused a small “revolution” among the spectators.

At a dinner among artists, young painter Maikel Sotomayor confirmed to me that it had almost become a cult object during the Havana Biennial. In Tokyo, Japan, it was the opposite. Distance was kept from the object, with medium curiosity and great modesty. Surely due to the conservative and content nature of the Japanese people, many questions remained in the air. But I was able to verify that hundreds of pubes had disappeared the day after they had been installed.

One of the most pleasant surprises that Pub(l)ic Manifesto has given me are the many people who write to me from social networks, send me photos of the object stored in their homes, and ask me to send them the written manifesto. This, despite not offering an accurate statistic on the level of awareness, does give me an indication of the interest it has aroused.

Each pubis has on its back the name of the city of the intervention, the object number and my name. That I am written to is an indicator that the questions that I sustain with the work have a degree of receptivity and expansion….

Do you “retouch” the idea to display it according to the peculiarities of each audience?

Due to the universal character of the symbol, I have decided not to make changes in its material appearance or in the drawing details of its representation.

Is the field and/or bibliographic research that precedes the gestation of the series hard work for you?

Not all the works that I do have a bibliographic support; most of it comes from intuition and personal feeling. However, once the idea is gestated, I dedicate myself to looking for other possible arguments or approaches to give it a historical and experiential grip. As my work is usually multidisciplinary, this research not only takes place around the theme, but also around the format; but it never precedes the gestation of the series, which is generated spontaneously and emotionally.

I approach the subject in an organic and non-methodical way; based on a contingent or experiential perspective. I fluctuate through deep and continuous emotional changes, a kind of spark that leads me to produce all kinds of work. It is in this unstable fluctuation that I find my ideal support. I am my work.

It seems that the controversy between conceptual art and other manifestations that are inscribed in “traditional” genres has aged. Is art possible without concept?

If anything is possible in art, it is absolute freedom. If something is fundamental, it is absolute freedom.

The role of curators has grown over time. From a simple curator, they have become a cardinal piece in the story, projection and revitalization of the artistic work. What relationship do you establish with the curators?

As in any profession in the world, counterparts are sometimes sought, but they are almost always found. There is no formula. Many times the encounters turn into disagreements, and others are consolidated as friendships, far beyond the professional role.

The curator-artist relationship must be based on an organic, reciprocal functionality. Curators contribute to accrediting, to legitimizing the work from the conceptual and technical point of view; and they can also have an impact on the art market as long as their practice is sincere and not promoted by other factors. Despite any professional, personal, or other relationship, the validity of the curator’s criteria will always be conditioned by the degree of honesty. I am extremely fortunate to currently work with David Mateo, who I could point to as an example in his medium.

Your home workshop is cited as a benchmark of avant-garde Costa Rican architecture. How empowered do you feel there? Do you long for the bustling and exciting New York days?

I have the great luck of not longing for anything, as they say: “been there, done that.” My life has been very rich in experiences, in dreams, and what I have lacked to live, I live through my work. My house and my workshop are consubstantial spaces, scenes of confluences, corridors where I display all the protagonism of my daily work. Beyond feeling empowered in them, they keep me busy, sufficiently immersed in everyday life, not to compromise with the “unbearable lightness of being.”