Michel Mirabal, who was born in a tenement house in the Cayo Hueso neighborhood of Havana, remembers that as a child he “felt a great twitching in his hands” that only subsided when he began to draw. That’s why “while I waited for my turn to bat in the pick-up ball games that sprung up on any corner, I would take out my little notebook and started scribbling.” He says that such was his desire to express things that when he was about six years old, he refused to talk for about three months and only communicated through drawings: “I was fascinated by that experience because it gave me the possibility for people to understand me through my drawings,” he says with a mixture of pride and mischief.

The visual arts world opened up for him when he was still a design student; he began working with maestro Omar Corrales, one of the most renowned set designers at the National Ballet of Cuba (BNC). “That experience lifted me up and it was the exact moment in which I began to design and to paint and to understand chiaroscuro and large-format art. It is a parallel world in which I was lucky to be able to grow, create, and carry out the work.” As a curiosity, it is worth noting that even today, the fifteen-meters-tall sets used at the BNC in the different versions of the emblematic ballet Swan Lake are the work of Michel Mirabal.

But his time at the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) was also decisive in his formation. There he worked as a storyboard artist, whose role is to be by the director’s side, making sketches on demand; obviously, it is a specialty that requires a rigorous training in the art of drawing.

At the beginning of his career Michel Mirabal created a character that, for an extended period, was the center of his attention: it was a hand that could have feet and a head and that “went around the world doing and undoing like humans do, that is, disrupting, decomposing, loving and also killing.” It’s a series, he says, that reminds him of “very nice memories” and that he dedicated to the mother of his first daughter. Then came the multimedia photographic series of the streets of Havana and the interiors of the solares (housing tenements).

Then his flags appeared, and at this point in our conversation something clouds his eyes because there have been, he assures, “incomprehensions” and people who “have certain misperceptions” and who see and detect ghosts where there are none: “There are wires and flowers in every country and, in fact, in my work the flowers grow over and neutralize the wires.” He acknowledges that his artwork can be controversial yet “very honest” and his intention in dealing with different topics is as mature as it is reflective: “not from the position of a bad boy who wants to attract attention. That’s not the idea.”

This artist, with an imposing physical presence given his size and gesticulations, raises his voice and speaks in a very Cuban manner, saying that he is “willing to participate in everything he’s called to: I love my country and everything about this island and although I represent my country to the world, I won’t allow anybody to speak ill of Cuba, whether what they say is true or not. I’m completely open to participating in any project that I’m invited to.”

These days he’s busy preparing a personal exhibition as part of the collateral events of the 13th Havana Biennial, to be held in April. “During the days of the Biennial,” he says, “my front door will be wide open to receive anyone who wishes to see my work up close.” And surely there will be talk about art and culture broadly because Michel is an excellent host who receives many visitors with pleasure: “At my house I’ve hosted people from the King of Morocco to famous Hollywood movie stars.” His large-scale pieces can be found in the collections of important institutions such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the Fine Arts museums of Medellín and Bogotá in Colombia, as well as the Martin Luther King and Afro-American foundations in New York. His artwork is part of the private collections of important figures in the worlds of culture, sports, and business, such as Gabriel García Márquez, Mohamed Ali, Danny Glover, Angela Mizzoni, Quincy Jones, and guitarist Carlos Santana, among others. President Barack Obama was presented with one of his pieces during his visit to Havana in March 2016.

Michel Mirabal, who currently works with two important galleries in the US—one in Aspen, Colorado, and another in Miami—emanates his work from there to the world, but without losing— “not even for a moment!”—his very humble Cuban upbringing.

Perhaps that is why he decided to build his house-gallery in the community of Marbella, a small town on the top of a hill near Guanabo beach, some distance east of Havana. He has developed some initiatives—in coordination with the local authorities and the State—that bring joy and culture to life there. His house is “always open” to three orphanages that he stresses are well-run by the State. “I invite them to paint, I cook spaghetti, or we all go to visit the National Museum of Fine Arts or to Varadero. I also pay attention to the community’s elders. I feel that this is a small way to give back after how much life has given me,” he concludes emphatically.

LOCATION

Studio address: Avenida las Américas 2E and Final, Reparto Ampliación de Marbella, Guanabo, Habana del Este

E-mail: mmirabal37@gmail.com

Tel: 77962079

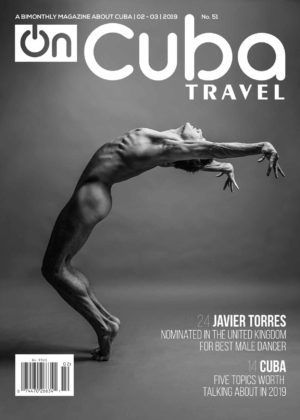

This article is included in the 51st Edition of OnCubaTravel Magazine: