“Miguelito, there are some foreigners who want to make a documentary about us,” Los Zafiros’ El Chino of said one day to Miguel Cancio. A while later, Cuban television was exhibiting a film telling how Ignacio had died at 81 from a cerebral hemorrhage. El Chino was an alcoholic and lived in Havana, and the other survivor had emigrated from Cuba in 1993. It was Heridos de sombras.

“That material was very painful for my father,” says Hugo Cancio, the oldest of Miguel’s four children, “especially because when El Chino told him that, he thought it was a lie, that it was delusions due to his inebriation.

“He also felt very bad because the documentary did not do justice to the career of Los Zafiros. I remember that I told him: ‘Don’t worry, I’ll go to Cuba and I’ll make a documentary that shows the other side of the coin.’”

That was the start of Zafiros, locura azul. The film that later evolved into a feature length with actors directed by Manuel Herrera started off as Hugo’s promise to his father to feature the history of a sweeping musical phenomenon in the Cuba of the 1960s: Los Zafiros.

The film, premiered in the 1997 International New Latin American Film Festival of Havana, was a box-office hit that year. It won the popularity prize of the event and was shown for eight months.

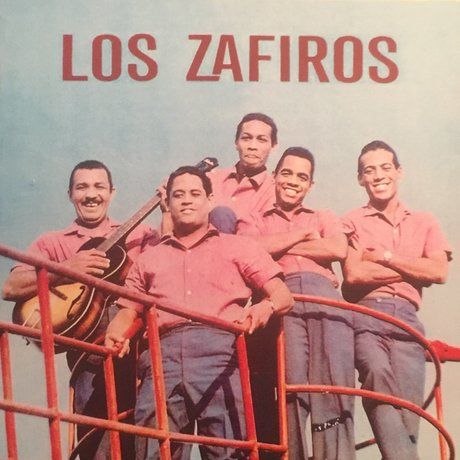

Decades later, the songs of that vocal quartet and a guitarist were being echoed. They had irrupted on the Cuban scene two years after the revolutionary triumph, mixing bolero, doo wop, bossa nova and rock, with an influence of U.S. groups like The Platters.

Twenty years after the film and 56 of the group’s foundation, Miguel Cancio, the only living member of the group and living in Miami since 1993, overcome by emotion tells OnCuba the story of Los Zafiros, its good decisions and what led to their end.

How did Kike, Miguel, Ignacio and El Chino meet? And how did they get to be Los Zafiros?

This is the story: I used to know Kike, Hugo’s uncle on his mother’s side, and knew of his musical talent. At times we used to get together and we did our jam sessions.

One day he calls me so I would hear a voice on the phone. On the other side of the line Ignacio was singing and I was fascinated. Then I immediately went where they were. I asked him if he had any other friend who sang and he told me about El Chino.

The following day he came by with his friend and when I heard him he also impressed me a lot. I remember that the test song was “Herido de sombras.”

Then came what we would call the group.

We got together to think about that at a bar that I used to frequent a lot located beside the Astral movie theater. I don’t remember if it was Kike or Ignacio who proposed Los Faquires.

The idea of four mulattoes wearing turbans in the tropics didn’t seem logical to me. We also thought of gems but almost all of them had been taken by quartets and groups like The Diamonds.

At the time I was wearing a ring and El Chino all of a sudden asked me what stone it was. I said a sapphire [zafiro], why? And we all liked the name. And that’s how we started being called.

After so many years of popularity in Cuba and abroad, what caused the dissolution of the group in 1975?

In the first place we were four persons with different characters, which on occasions affected us, although it was not so serious for the group to dissolve. We were always able to overcome those situations.

We were very fun-loving and humble persons, despite the popularity we had reached. We used to sing in a tenement house or in a cabaret. We came from the barrios and we always returned there.

I believe that, apart from being liked for the vocal work, the people followed us for the way we were.

One of the events that most influenced the decline of the group was the cancelation of a second tour we had in the former Soviet Union. It consisted of four months with performances together with Los Papines, Rosita Fornés and other artists, in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Hungary and Germany.

We considered it was going to be too tiring for us and we gave up continuing on that tour. We were immediately sent back to Havana and when we arrived at the airport no one was waiting for us.

That’s when the debacle occurred; when television and radio was closed off for us. They “cut off the power” for us for a long time.

I think that created discontent and disappointment among us. And the recourse that appeared was alcohol, my friends’ only vice.

Afterwards we had another period of performances in cabarets, until Manuel Galván, the guitarist and musical director at the time, decided to leave the group.

I was again left as the director, but I also left it afterwards because things were no longer functioning as before.

They continued singing and I went to work in the Center for the Contracting of Artists. Later I left to sing in Camagüey as a soloist until in 1980 I had to abandon music.

***

That year Miguel authorized his two oldest children to leave through the Mariel maritime bridge. After that he was expelled from work and he was left with no links to cultural institutions.

Sometime later, when both of them were already living in the United States, he wrote to Hugo: “Don’t worry, son, they could expel me from culture but no one can take away my feeling as an artist. I’m working as a mason but I go to work every day wearing my three-piece suit.”

In 2001, Miguel Cancio returned to Cuba for the recording of the documentary Los Zafiros: Music from the Edge of Time, by Lorenzo D’Stefano.

The idea was that the only two living members tell in Havana the history of the group: a duet testimony by Cancio and Manuel Galván.

“That reencounter with Cuba was more moving than the film and even the documentary. The welcome of the persons in the barrio of Cayo Hueso and in all the places through which we passed was fantastic. None of us ever thought we would have such a big impact in the heart of our people.

“The ‘new’ Zafiros also existed in Cuba. In Trillo Park we got together with them and we sang ‘Un nombre de mujer,’ better known as ‘Ofelia.’

“The visit to the cemetery and to the tomb of my friends was also very moving during that trip,” says Miguel. “Perhaps some took the explosion of the bottle as an insult, but it was my impulse because of the pain and rage I felt due the alcohol that had done away with the lives of Kike and El Chino.”

***

Los Zafiros was a family history; that of the father of Hugo Cancio and his uncle Kike, Leoncio Morúa, his mother’s brother. And it’s also his maternal grandfather paying for the first wardrobes of the quartet and taking them to sing at Varadero’s Oasis Hotel. “Los Zafiros emerged in my home,” says Hugo, president of Fuego Enterprises and founder of OnCuba Magazine. “It’s a very personal history.”

How has it been to be the son of a Zafiro and growing up with all that musical influence?

It was not a normal father-son relationship. I have memories of my father getting ready to go to the cabaret with Los Zafiros. The great Cuban artists would pass through my house in Varadero when they were visiting and they ended there with jam sessions. After his separation from my mother I remember that he would go every month to Varadero to see us and also because Los Zafiros had a show in Varadero’s Internacional Hotel which was called “Me caso con una sirena” [I’m Marrying a Mermaid], with Armando Bianchi and Rosita Fornés. Those memories are very alive.

I come from a musical family. My mother sings, my uncle Lázaro Morúa was in Los Van Van. On my mother’s side my grandmother had seven sons. They all promised to become doctors and they all left their university careers to make incursions into music.

Thus, despite reading music since I was 8 years old and playing percussion (I already forgot to read music), I never devoted myself to music because of those curious advices of my grandmother, who used to say to me every morning when she would take me to school: “Study so you won’t have to be an artist.”

Afterwards, how did Los Zafiros’ music accompany you in your life?

The truth is that when I was young I was allergic to Cuban music, except for Los Zafiros.

I grew up in Varadero with all that influence of tourism, where U.S. television and radio stations were seen and heard at home, so I was very permeated by The Bee Gees, The Beatles, Donna Summer and all that music from the mid and late 1970s.

I was a “pepillo,” as it was said at the time, with a tremendous ideological deviation from the cultural point of view.

Then Cuban music was not part of my day-to-day life. However, Los Zafiros were always there.

My inclination for Cuban music came after I left and the first time that I returned to Cuba. My life took a 180 degrees turn and since then Cuba became a priority. I started promoting it as a country, a destination, a cultural power; an endeavor that still continues.

How did you come to produce a film about Los Zafiros? And how difficult was it for a Cuban American to achieve that in the political context of the 1990s?

I started coming to Cuba to search for material about Los Zafiros in Cuban television to make a documentary. An incident led to the work becoming a film.

After some time compiling information, I again arrived in Cuba and was practically expelled from the Cuban Institute of Radio and Television [ICRT]. They told me that Enrique Román was no longer the president and that the new leadership had decided that Los Zafiros were national heritage and that I had nothing to do there.

The Department of Consular Affairs and Cuban Residents Abroad (DACCRE) already existed and its director was José Ramón Cabañas. I went to see Foreign Minister Roberto Robaina and commented to him the idea of making a movie – and I used the word movie instead of documentary – about the history of Los Zafiros. Then they put me in contact with the Cuban Institute of Cinema Arts and Industry [ICAIC], with the Ministry of Culture and the term movie was repeated over and over in those places until we finished making that: a movie that cost me almost a million dollars.

I don’t regret having spent that amount even though I will never market the film. It never came out in video nor was it screened in any movie theater commercially. The sentimental value I gave that project prevented me from selling its copyright.

Those were difficult times when there was no exchange between Cuba and the United States. What we did was a combination of premeditated risk and total naiveté. I said: “I’m going to do it because I have the right, it’s my country, my culture, the history of my father…,” and with that conviction we continued with the project.

It was the first film made independently from ICAIC. The agreements were signed with RTV Comercial which had just been created and the services were bought from ICAIC.

How was the film’s premier in Havana? Did they feel that Los Zafiros were still part of the Cubans’ imaginary?

I always thought the film would be a failure in Cuba, because the people didn’t remember Los Zafiros, the young people listened to another type of music. And I was so moved when I got to the Payret movie theater that evening for the presentation of the film and I saw 10- or 12-block-long lines and I started crying like a baby.

We entered the theater and, as we did afterwards for two years when presenting it in diverse festivals in the world, we sat in back to see the public’s reaction.

It was an unexpected phenomenon, all of a sudden children in the streets started to make choreographies of Los Zafiros.

It is without a doubt one of the most beautiful projects I have carried out in my life.

That year we won the popularity prize in the New Latin American Film Festival of Havana as well as many others abroad.

It is a work that belongs to me, 100 percent independent, but at the request of the Cuban authorities I later donated the film’s copyright for its distribution in national territory.

“That was incredible. At that time it was one of the biggest box-office hits in Cuba’s history,” adds Miguel.

I asked him what Locura azul still meant to him: “For me that film represented a lot, of course. They are very important memories, because my comrades were like brothers to me. I believe we were born to sing and life brought us together. That it was written. We didn’t know each other and when we met it was an immediate connection. The film was able to sum up the group’s spirit and that’s what’s most important.”

Which part moves you the most?

The arrangement of the number “Habana” which appears at the end with images of El Morro is spectacular. If I see it again tears will well up in my eyes.