I didn’t have to ask around much, they knew right away who she was. It’s really a shame, but very few like her remain. That is why I came to this bar. The writers were right. Places that operate at night should never be seen in daylight. All the dust, all the sorrows recounted by those great boleros seem to come out of the songs and drift in the air like haggard daytime ghosts. There she is! As soon as she hears me arrive, she lights up, and it’s as if all of the vitality of yesteryear had returned to her body; it’s no longer necessary to ask her.

Yes, Mr. Journalist, I am the “record-player” they told you about. I’m not going to tell you my age; you don’t ask women that question, But I can tell you about her because I was there, you know. So, you want to write about Freddy? Well, yes, I knew her. She was a servant, and she would come at night to the place where I worked. Moreover, I heard her sing, right there, sitting next to me, at the bar of the Bar Celeste. Sometimes she was accompanied by one of my records, but other times it was just her own voice. Which was enough and more than enough, to be honest.

What was her voice like? Let me tell you, it was enormous, almost like her. Certainly you’ve been told that Freddy was fat, very fat; they say she weighed more than 300 pounds. And black. And poor. Yes, there are photos; you can see her. She was gigantic. Although there is speculation even about that. The few people who talk about her always add a few more pounds. Let me tell you, there are many things that nobody knows for sure about Freddy. They say that her name was Fredesvinda García Herrera. But some say it was Fredelina, and that her second surname was Valdés. Some write that she was born in Matanzas, and others say it was Camagüey, and that she came to work as a domestic in Havana. That she was born either in ’33 or ’34…. Nobody knows where her grave is in Puerto Rico, either. Because that’s where she died, in 1961.

Of course, you asked about her voice; I sometimes get distracted, it’s my age. Are you familiar with “The man I love,” that song by George Gershwin? Or Cole Porter’s “Night and day?” Or “Noche de ronda,” by the maestro Agustín Lara? Well, you have to hear them sung by Freddy. It’s true that the arrangement that was recorded was not the best. Her voice didn’t need all that big band in the background. And the lyrics in Spanish are a little stiff. But that voice, oh what a voice.

Look, it is not the clear voice of Ella Fitzgerald, or the resigned heartbreak of Billie Holiday, or the tranquil, sure voice of Etta James. It’s all of them at the same time, in an outrageous, superhuman and divine mix, like her body. Freddy had a thunderclap in her throat. But not a clattering, ephemeral thunderclap; it was more like a dense river. Intense and serene. A delicate thunderclap that she surely used to try to take all the sadness out of her soul, and that she slowly let fall, soaking whoever heard her. You have to feel how that voice falls, drenching you with sweetness, pain, and nostalgia. What a tremendous contralto.

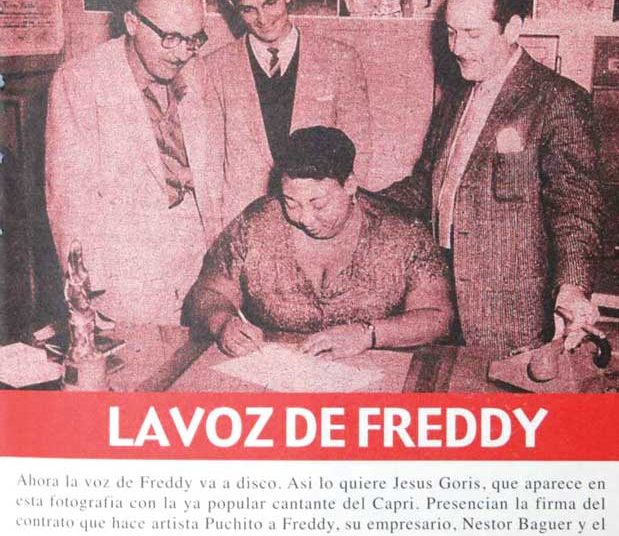

Yes, she made a record. Only one, unfortunately. It was recorded in 1960, under the Jesús Goris label Puchito, as Noche y día (Freddy con la orquesta de Humberto Suárez). In another, I think more modern edition, it was called Freddy. La voz del sentimiento. And several more editions have come out. But no, no way. I, who heard her, who saw how she cried oceans with every verse and seemed to bleed to death and squeeze out the last drop of life from every song that came out of her throat –of course by giving her own– can tell you that this record does not have even half of what Freddy could do. And notice that none of the composers whose songs she performs are easy to sing. Go ahead, just tell me who is bold enough to sing Agustín Lara, Piloto y Vera, Consuelo Velázquez, or Marta Valdés. You have to know a lot for that…

They say that yes, afterward she became famous and even appeared in a book. That was because some friends of G. Caín –I think it was the drummer, Eribó; or Códac, the photographer; or Silvestre, I can’t remember now– took him to hear her sing, and she inspired him to write a novel. After that you could rightly call her The Star (La Estrella), like the song that Ela O’Farrill composed for her.

Of course, of course. She performed in cabarets. She appeared on television. With Benny Moré and Celia Cruz, no less; I think it was on a Partagás show, if my memory doesn’t fail me. And she worked in Venezuela, in Mexico, in the United States. Until she went to Puerto Rico… that’s where she died, when she still had so much more to sing.

You’re leaving? Of course, I’ve been talking your ear off… I hope that Freddy has become a star and shines in the eternal night, as a verse from O’Farrill’s song goes. In any case, Mr. Journalist, the next time it rains, listen and listen carefully. It just might be that one of those thunderclaps –the ones that sound far off and last a long time– is due to Freddy. Who knows? Maybe up there, in some kind of heaven, her voice is still crying a bolero to console us in our sadness. Maybe, when I kick the bucket, I’ll be able to accompany her again with one of my records, like we used to do in the Bar Celeste. And that’s it for now, because I’m getting all choked up. Go now, it’s getting late. Bye-bye, Mr. Journalist. And come back whenever you want…