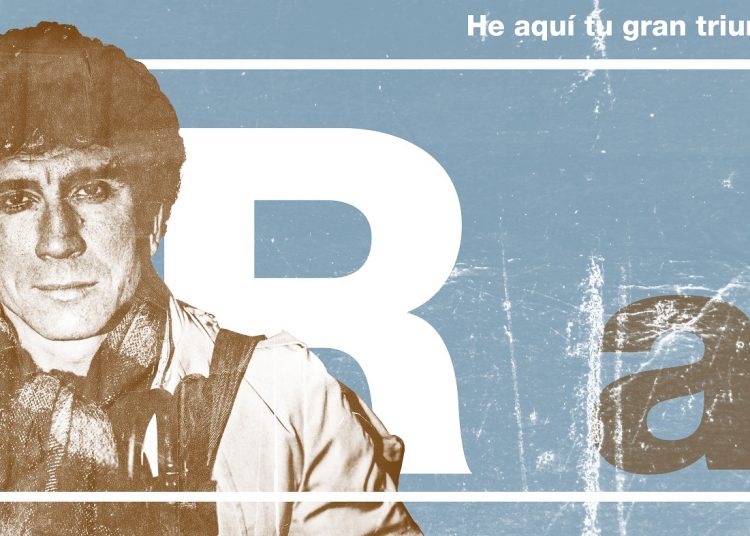

On December 7, it was 30 years since the death in New York of Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas (1943-1990). It was not a natural death, it is known. Arenas chose to end his life haunted by circumstances. Perhaps the heaviest at that time were those concerning AIDS and exile.

Beleaguered for being a homosexual in Cuba during the time of the parametrations, exiled during the Mariel, frowned upon in Miami for the same reason, he had no choice but to be ruthless in his reviews of his existence.

Reading him, one can see that he transformed his sexuality into the greatest dissidence, exaggerating delirious episodes and dragging those he knew, admired or suffered along the same path that he would very well describe as “queer,” and that in his narratives, because of the meaning reached by this transformation, means more than what it literally denotes.

https://oncubanews.1eye.us/gente/delfin-prats-por-holguin-antes-que-anochezca-i/

Said with a desire for synthesis, in Arenas’s literature the term “fag” acquires the character of a philosophy from which he manages to describe what for him, with a parodic look, not devoid of tragedy, seems an inevitable fact

in the history of the island: suffering, submission and simulation.

Although a radicalized anti-Castro, we have in Reinaldo Arenas one of the few writers from exile to whom discreet and continuous tributes have been paid in Cuba. He was probably the first of the “cursed writers” to be tolerated by a state institution. It is true that he has not been the subject matter in the news, but the tribute takes place once a year in the city of Holguín, thanks to the efforts of the young artists gathered in the Hermanos Saíz Association (AHS) and, specifically, those who work in Ediciones La Luz publishing house.

“It is not fortuitous that from Holguín, those who were young writers at the end of the 1990s ventured in an enterprise that didn’t go unnoticed by few, who preferred to maintain a healthy distance from those enterprising and enthusiastic writers admired in Arenas’ work. The award began with the provincial urgency to only summon authors from the province. Perhaps Ghabriel Pérez, its founder, never thought that 20 years later other young people would continue to bet on that same award, so many times endorsed by the quality of the winning works and a luxury jury (I remember names: Guillermo Vidal, Eduardo Heras León, María Elena Llanas, Jorge Ángel Pérez, María Liliana Celorrio, Sergio Cevedo.…),” poet Luis Yusseff, director of Ediciones La Luz, tells me.

With the Celestino award Arenas’ name was mentioned again in the city, where he returned through one of his characters, transformed into a symbol of a new contest. Thus was born the Celestino Short Story Award, which recalls the character of the only novel published by Arenas in Cuba: Celestino antes del Alba (1967). Dawn and Sunset. Day and night are extremes that abound in the literature of he who was also a playwright and poet.

It is true that it is the custom of the bureaucracy to deny anti-government writers when they are alive, that such a recovery usually occurs only when they perish and that, in this way, the system ends up scoring a point in favor of those who suffered its marginalization. But it is also true that many times it is the authors, for ethical, sentimental, intimate and commercial reasons, who do not want to publish on the island, and that the return of their work represents, above all, the effort of those who from within, even from the institutions, think differently from what is understood as official.

“Perhaps, from the place where people who commit suicide go, Reinaldo Arenas is looking at us with some suspicion, but also with the intimate delight of someone who knows that those marks on the trees of Perronales have never been erased in Cuban literature,” Yuseff warns.

A fact like this demonstrates the diversity of Cuban society and underlines the heterogeneity of voices to which the state media will have to open up at some time, so that people stop believing that everyone in Cuba thinks the same way, overriding with this the effort of those who also fight against ignorance, without their effort ever being publicly acknowledged.

Just to mention writers, I would like to find in Cuba as many busts of Pablo de la Torriente Brau as of Guillermo Cabrera Infante and of Arenas, the man who made a novel of his life, written with elegance and sensitivity, leaving the trace of his powerful voice in it, where sarcasm and mockery, the bucolic tone of childhood, poetry and the perpetual desire to challenge the reader, questioning him where it hurts the most: sex, stand out.

Since the publication of Celestino antes del alba, Arenas had become a young talent who kept his promise, even if at times he had to put his existence on the line to achieve it. How much truth is there in what he wrote in his books? Surely everything, although much of it is based only on a tiny portion of reality, because we already know that this is how literature works.

It has been said that even his biography is determined by the prodigy of his imagination, an aspect of his narrative that reaches impressive levels in books like El Mundo alucinante (1969), El Color del verano (1999) and even Otra vez el mar (1982), a book that a scholar like Alberto Manguel considers “perhaps the most successful novel” of he who makes a connection in associations with Lezama Lima, Virgilio Piñera, Severo Sarduy or Cabrera Infante himself.

I keep an anthology of Cuban short stories published in 1969. It brings together 15 authors. In it names are missing, of course, but it gives an effective overview of the genre for the year of its publication. It is titled 20 cuentos cortos cubanos and the penultimate one was written by Arenas.

In that short story (“Con los ojos cerrados”) there are many recurring themes in his work: childhood, death, poverty, the phantasmagoria of poverty, mother, childhood…. The editor of that book writes that, with Celestino, the theme of childhood and the child as a character had made its entry into Cuban literature, where until then it had been a matter rarely raised.

Childhood was vital in the life of someone who was born in Aguas Claras, a rural area located north of Holguín, a city that made Reinaldo Arenas suffer the weight of a province until he abhorred it. It is there, however, that every year he is now remembered in panels and talks.