MDM: These acronyms can mean many things, from Mobile Device Management to Mechanically Deboned Meat, a basic input for the production of different food products — from a succulent hamburger to a croquette, logically including hot dogs. However, I learned about this relatively recently.

My first encounter with those acronyms was in my first year of Economics when I had to read Karl Marx’s Capital. In Marxist political economy MDM — generally written M-D-M — expresses the commodity cycle in which the ultimate goal of the act of exchange is to acquire a commodity to consume it; this means that money is nothing more than the means to acquire a product whose use value we seek.

It is a very synthetic way of expressing the act of exchange and illustrates very well its final purpose: to consume to satisfy a need. What is interesting here is the capacity of that commodity to satisfy that need. In the development logic of commercial relations, this formula was preceded by another, M-M, which expresses that same act of exchange in the absence of money and which we normally call barter. Each owner of a product exchanges it for another seeking to satisfy each one’s needs.

We Cubans with some accumulated experience know this last act of exchange well and we have practiced it for decades, especially in that glorious era of that ration card that provided countless goods — including branded beers — at very low prices and for all Cubans, regardless of their tastes, their consumption habits and even, almost even their income.

Thus, the exchange of cigarettes for condensed milk, rice for sugar, butter for cans of spam… All of these exchanges, even when they were not officially welcomed, were admitted. The shortage! that we suffered in those times was an objective factor that justified it “morally and politically,” while the egalitarianism derived from “rationing” was another of those reasons and logically, the Phoenician genetic ancestry of the Cubans was the other.

It was not frowned upon that from time to time one entered into that type of bartering to correct that small defect of egalitarian distribution. It was in some way the obligatory side effect of the “what’s owed to me” disease, the same one that many of us still suffer from today.

The formula M-M-M, however, in political economy has a different meaning. Here the purpose, the objective, is money and merchandise (M) and its use value is nothing more than a means to reach money. It happens that it is also the way to obtain more money and then the expression becomes M-M-M’, where M’ means increased money and simplifies that long and old process that is commerce.

Centuries had to go by for humanity to move from bartering — often fortuitous — to commerce as a specific activity that allows those goods to be made, increases the capital invested, and facilitates the satisfaction of multiple needs.

Walking around for a whole day with a bunch of plantains to exchange half of them for a pound of lard that allows us to eat a few fried plantains is not the most efficient.

So commerce also fulfills other important functions: saving people time, selling them the necessary goods, allowing production to be carried out, reducing production time, and wealth accumulation that can then be invested to increase that same production.

Towards the end of the feudal mode of production, monarchs identified the monopoly over the trade of certain products and territories as one of the most effective ways to increase their coffers.

The monopoly of trade with the Indies, Western and Eastern, was always a very well-used resource while the monopoly on some products became a source of income for those States. In Cuba, the “tobacconist” is almost always what comes to mind.

In our country, for several decades since 1968, practically all trade, both foreign and domestic, was “exploited” by state enterprises and structured vertically from two ministries in charge of “developing and controlling” the activity.

There would be a lot to talk about foreign trade in Cuba but it will be on another occasion. Suffice it to say that exercising a monopoly over it has been identified as an essential condition of socialism, even though there is no practical or theoretical evidence that this is the case. Its results, all influenced by “special” conditions which include everything from the U.S. blockade to the “fraternal and supportive aid of the USSR, have always left the bitter taste of a persistently negative balance of goods; a high dependence of exports on the capacity to import; a high geographical and asset concentration and a weak and not very dynamic international insertion.

We must remember that commerce is always the staging of the work, which requires a lot of previous work, adding the efforts of many to achieve good results in this objective of exporting.

What concerns us today is domestic trade. Also monopolized for decades by state enterprises, this “sector” today concentrates 19% of all state enterprises, its participation in the GDP reaches 15.2% — manufacturing industry is 8% and agriculture is 2.2%; it employs 414,600 people, the fourth sector that employs the most people with 9.2% of those employed and the third in female employment and has been one of the main sources of income for the state budget as will be seen further on.

Domestic trade and foreign trade are indeed two very different areas, with different functions and relevance, but both are very important, in the operating model of a socialist, underdeveloped and blocked economy.

The fact that commerce was entirely state-owned was assumed as a “regularity” of this underdeveloped socialist functioning. It was, at the same time, an economic resource, which allowed the State to appropriate the capital gains it generated and allocate them for various purposes. It was functional for the central control of the economy that our model, under those conditions, required.

Domestic trade has been, and still is, one of the most important sources of income for the State and its budget, regardless of the efficiency of its management. However, something has changed. The opening of trade to the non-state sector has introduced new variables into the country’s growth and development equation.

By 2018, Cuban households spent 68.8% of their total consumption expenses in the state market. Cuban households spent 73.8% of their consumption expenses between the state market and the agricultural market. The importance of the state monopoly on domestic trade is perfectly proven if we take into account that already in 2018, with a certain opening of trade towards other actors, the Road Tax continued to be the main source of tax revenue (41.4%) while taxes on profits and contributions from state enterprises reached 16.6%. In that year the road tax was 2.4 times higher than the tax on profits.

What has happened between 2018 and 2022, as we see in the 2022 Statistical Yearbook, published by the ONEI in 2023, is that the spending of Cuban households outside the state market has grown considerably.

In 2022, in the structure of household spending, the weight of the state market had fallen to 53% and household consumption in the state market and the agricultural market was reduced to 56.69%, losing more than 10 percentage points in five years, while the participation of other markets in this expenditure grew from just over 26% to more than 48%, fundamentally favored by the growth of the so-called “other sources” that increased their participation to just over 18%.

The structure of budget revenues has also undergone significant changes. The participation of the Road Tax has been reduced and its weight in tax revenues was only 6.8% in 2022, consistent with the shift of consumption towards non-state markets.

All of the above could explain, at least in part, the insistence on the part of regulators to recover spaces for state commerce and the resistance to the expansion of the private sector in commerce. It is true that there can be and are ideo-political prejudices, but it is also true that from a practical point of view this State, which operates today under strong financial restrictions, loses, at least in part, one of its sources of income.

It is also true that the supply that supports this expenditure has increasingly depended on imports and that a part, not at all marginal, of that import and therefore of the supply, is supported by the non-state sector.

“Retail inflation in November was 2.29%. In November 2022 it had been 4.11%. With this result, a retail inflation index of 27.03% and an interannual index (Nov23/Nov22) of 31.78% accumulates in 2023 (January-November). Source: CubaSí.

What is apparently counterintuitive is that while these new non-state enterprises contribute to the supply and in some way have a positive effect on prices, the regulators maintain the intention of limiting and even demonizing non-state trade, as the cause of the high prices. When during the process of creating an MSME it has marketing as its corporate purpose or its associated activities, it is subject to other filters and the delay in its approval may far exceed the time “normally” taken.

What the facts show is that inflation and most of its causes — supply deficit, excess liquidity, fiscal deficit, exchange rate distortion — were already present long before the “birth” of SMEs.

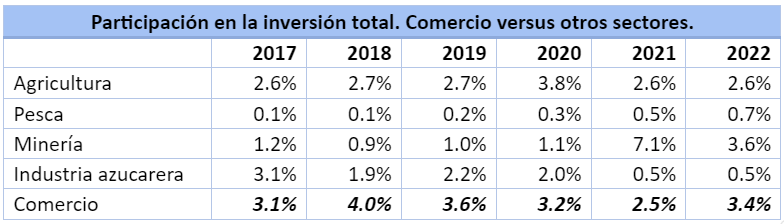

The facts also demonstrate, and for a long time, that the management of commerce by the State has been inefficient. The other thing that is verifiable with the data is that the commerce sector has had a greater participation in investment than several of the sectors that produce goods and that are decisive in the fight against inflation.

Agriculture / Fishing / Mining / Sugar industry / Commerce

Source: 2022 Statistical Yearbook of Cuba, table 12.3.

Is investment in the commerce sector really essential? Is it consistent with the situation the country is facing? How is it possible that having been recognized and declared several times as STRATEGIC, agriculture has less participation in investment than the commerce sector? What sense does it have for the State to invest in commerce when it has nothing to sell?

Wouldn’t it be more consistent to address the supply deficit to dedicate those monies to investment in the sector that produces goods and thus increase supply?

Couldn’t those monies be used to help those segments of the population in the most vulnerable situations?

There is still no official public data on the participation of SMEs in total imports this year, but given the situation of the sectors that the respective trade ministers have described in the Mesa Redonda TV program, this participation may have grown compared to the previous year despite “bancarization.”

What daily life also demonstrates is that today, along with an undersupplied, inefficient, and expensive state commerce network, another network of small private grocers and hardware stores has grown in all the neighborhoods. Certainly, at high prices concerning the salary earned and the meager retirements and pensions, but these grocer’s bring the products closer to the Cuban consumer, they maintain a certain stability in the supply of some of those products, they risk their capital and not that of the country and THEY DON’T COST THE STATE A CENT, NOR DO THEY COMPETE FOR STATE INVESTMENT.

Meanwhile, more than 9,000 grocery stores are maintained to distribute what remains of the ration card. These establishments today require logistics that are difficult to sustain. There also persists a network of large commercial establishments that require investment for their maintenance and that incur current expenses every day with semi-empty shelves and a meager variety of products. Their sales levels probably don’t pay what it costs to keep them open, costs that we all pay, and that include their inefficiency.

It would seem that unlike the arguments put forward, what is needed is more and better businesses in the non-state sector, more competition between them so that prices are modified and improved; and more concrete actions to protect the most vulnerable. What is needed is to think differently and act differently.