According to the Letter of the Yorubas, this year comes under the aegis of Elegguá, the one who opens paths, and Oyá, queen of cemeteries and hurricane winds. Let’s say, conflicting forces that, far from diminishing, reaffirm the contradictory nature of the real world and, instead of simplifying, make the vision of the future more complex.

In such conditions, it is not strange that the voluntarism of several politicians and the linear rationalism of some intellectuals converge, each in their own way, to obscure the present and above all confuse the exercise of predicting and the vocation of preaching. As if examining what happens was the same as giving an opinion and putting each person’s wishes first; as if there were no way to elucidate where we are and where we are going without taking sides from the start.

On the other hand, the priests of the Regla de Ocha, more modestly, give an account of what the oddun indicate, instead of putting their speculations and opinions above what the conchs say.

A simple inspection of the large-scale board that is the world today reveals what could be called the paradox of democracy: the more its defense as a doctrine and a global ideological banner extends, the larger the fissures that emerge in its practical exercise, even in countries considered paradigmatic.

In a former colonial metropolis and model of democracy like the United Kingdom, the head of government (not elected by universal and direct suffrage, but by his party), himself the son of ex-colonial immigrants, is not only advocating closing immigrants’ entry, but exporting them, as if they were toxic waste, to Rwanda, an African country characterized by insecurity and violence.

The republic that was born from a great revolution, under the motto of Liberty, equality, fraternity, and that previously experienced the fiercest religious wars in the West, has experienced conflicts of intolerance, religious violence and the rise of racism that reach record numbers, after a year of incessant street demonstrations in defense of retirement rights, while the government prepares to celebrate the Olympic Games, as if nothing were happening.

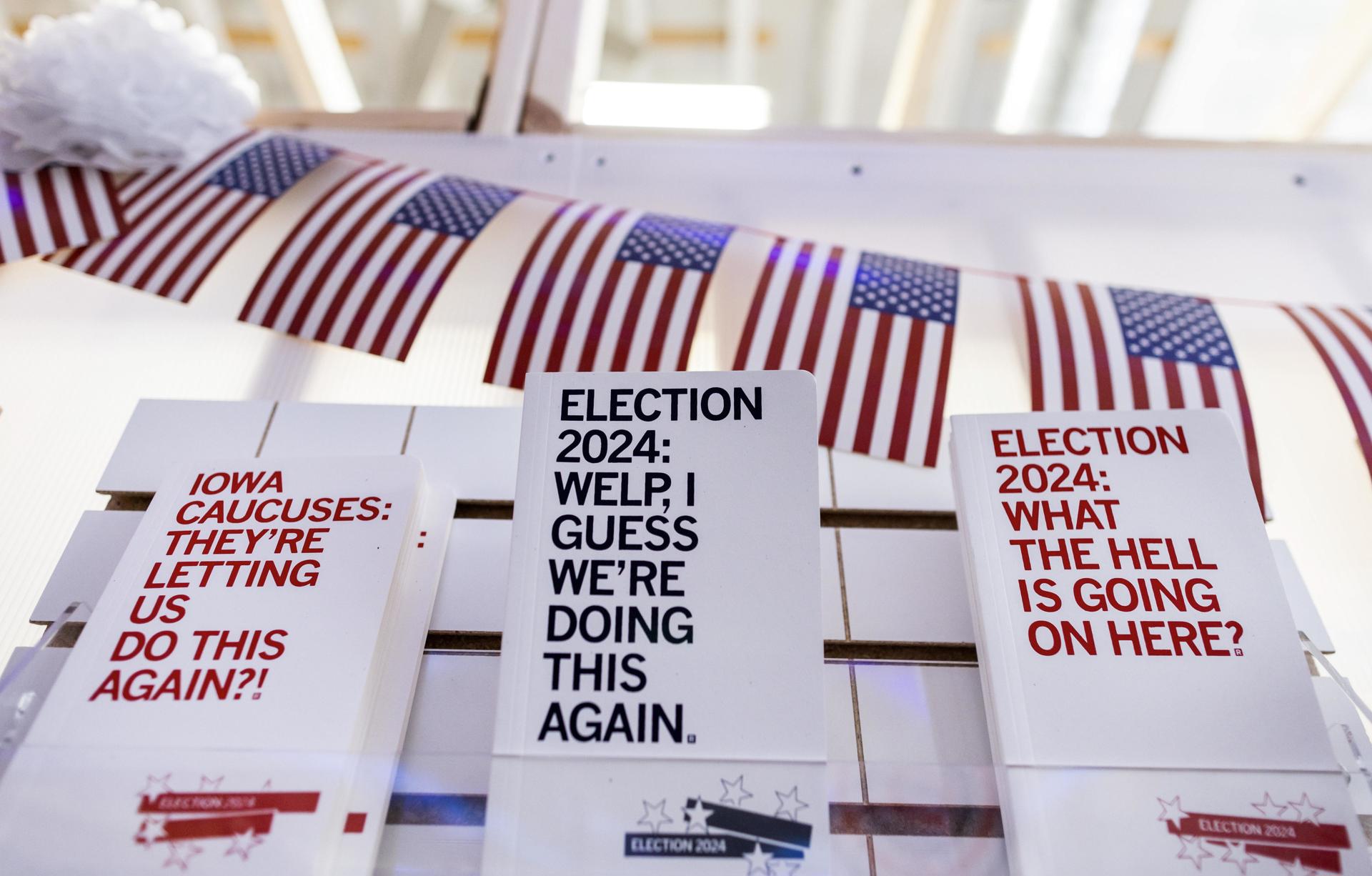

In the democracy considered the oldest in the world, people concentrate on their main political ritual: elections, which divide the population into two halves, in which a pair of candidates compete who accuse each other of being “communist” and “Nazi” respectively; that is, totalitarians.

If that were not enough, one of them, subject to several judicial processes for more than 90 charges (including inciting violence against the established powers), reaches astonishing popularity levels.

The latest thing in Latin America and the Caribbean, and also in the United States, is that politics is “judicialized.” In Peru, Colombia and recently in Guatemala, the Prosecutor’s Office, which is supposed to be independent as a judicial power, and the Congress, dominated by the right, have hindered the elected president and his inauguration, responding to the interest of a conservative establishment worthy of the 1970s. Let’s say that two of the powers conspire to block the third, and legalize a certain type of coup d’état against the elected president, as they have just done with Bernardo Arévalo in Guatemala, the first president to take office at dawn because the others did not let him.

To the extent that U.S. politics has become “populistized,” not only have Trump followers attempted to coerce, in the best style of a banana republic, established institutions (as in the assault on Congress); Democrats have also sought to use the courts (including the Supreme Court) to remove their opponents from the game.

Lastly, the international system (not the institutional order, but those who, as the Yoruba would say, “cut the cod”) is not much more democratic and distributed than it was in the years of the Cold War.

For example, two years ago Russia invaded Ukraine, a sovereign country whose territory does not belong to it, invoking reasons of national security. The Western alliance has blocked Moscow with all types of sanctions, economic, political-diplomatic, and demonizes its leadership in terms similar to the anti-communist rhetoric of the worst moment of the Cold War (although it is not precisely the RCP that governs Russia).

For its part, Israel, in response to the attack by an organization that does not represent the State or the nation, unleashes the bloodiest massacre of Palestinian civilians in history in just one hundred days, on a territory that does not belong to it. Although questioned by the international community, Israel does not suffer United Nations sanctions nor is it ostracized by the main powers.

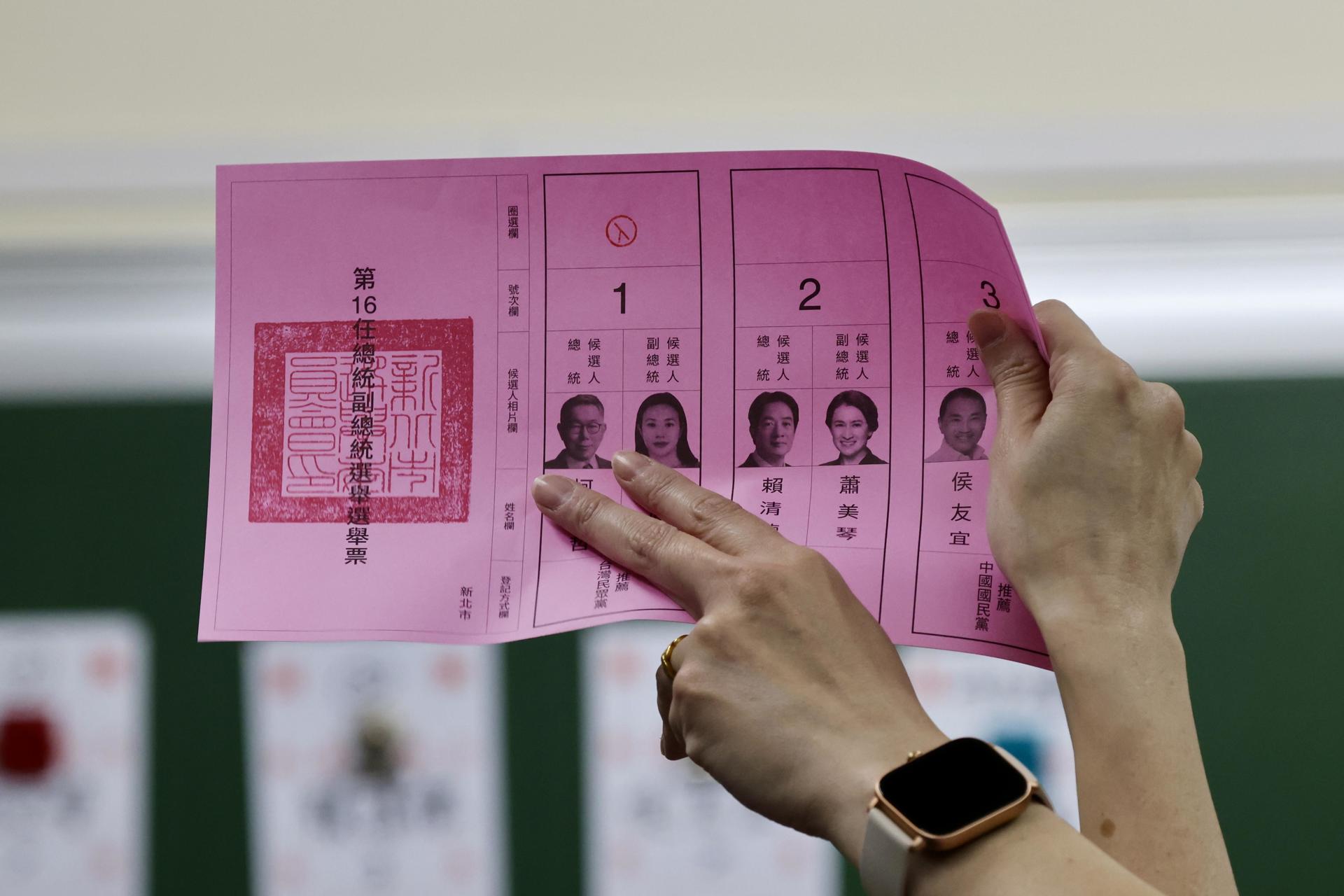

The last trendy feature of democracy is that the right becomes popular, to the point of winning elections. This is a right that exploits nationalism and prides itself on rejecting dialogue, the same in Taiwan as in the Republic of Korea or Argentina. So anticipating a 2024 in which 70 countries are expected to vote on their positions is not exactly an optimistic outlook.

The second paradox, closely related to the previous one, would be that of security, according to the memorable phrase of the illustrious President Woodrow Wilson: “Create a safer world for democracy.”

At the time of the Cold War, which some historians consider in force, the main perception of threat among the governments of our hemisphere was, supposedly, communism and pro-Cuban or pro-Chinese guerrillas. The remedy to avoid them, as is known, was the hypertrophy of the armed forces and their internal political role, which led to a chain of military dictatorships that spread between Central America and the Southern Cone, which completely ended the democracies themselves.

The second main security concern, especially for the United States, the Soviet-Cuban alliance, had climaxed with the Missile Crisis, and would have lasted until the Central American wars, where there were no Soviet or Cuban troops, but there was the political lure that the countries of the isthmus were going to become “satellites of the USSR.”

Returning to the present, it turns out that during the last twenty years, Russia has sold weapons and in some cases military advice, to numerous countries in the region (Argentina, Brazil, Nicaragua, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, Mexico) without the United States expressing concern or rejection. Paradoxically, all of those countries have had more recent Russian military cooperation than Cuba.

On the other hand, as is known, China became the main trading partner of the largest economies in the region.

Although some political analysts resist recognizing these differences — and many others — with the Cold War period, the main national security problem — and a real threat to democracies in Latin America — is no longer “communism,” nor is it Russia or China. In the absence of military dictatorships, the main threat is organized crime.

Let’s say that the Yoruba Letter, among whose main precautions is “the increase in criminal activities,” seems to be more focused than many independent observers on the hemispheric reality. Indeed, Latin America and the Caribbean closed 2023 as the region with the highest homicide rate in the world.

Among the countries with the largest population, this rate has decreased in some cases (Mexico) but remains high (Colombia, Brazil, Venezuela, Mexico). What is new, however, is that it has grown in other countries considered safe until now, such as Chile, Costa Rica, and dramatically, Ecuador, where the homicide rate exceeded that of the rest of the region.

If we land these paradoxes in the Cuban circumstance, we would have a group of contrasts, in themselves also paradoxical.

In terms of human safety, according to data from the same source cited above and from the Ministry of Public Health, the homicide rate would have grown from 4.42 per 100,000 inhabitants (2019) to 5.13 (2021), which places the island in 31st place among the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean. Although the increase would be within the parameters that were recorded within the framework of COVID-19 (in the United States, homicides increased 29% in 2020-2021), the main difference is in the organized crime factor.

Some commentators who address the issue overlook that, if it is a comparison with Latin America and the Caribbean, and with the United States, this notable difference cannot be ignored: despite being in the heart of the Caribbean, on the routes of the historical drug trafficking to the United States, and the main industry is tourism, no law enforcement agency in the United States or other countries has been able to document the existence of organized crime networks on the island. This is a fundamental factor that explains, according to specialized sources (Insight Crime), half of the murders in the region.

If, as some say, Miami is the second city in Cuban population, it would be worth mentioning that the homicide rate there triples the national average, and that in 2022 it was 18.6 (per 100,000 inhabitants), three quarters of which were caused by firearms. Above Mexico City, and the national rate of countries such as El Salvador, Panama, Nicaragua, Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, Peru, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Cuba, Chile, Bolivia.

The other relevant difference in human safety for comparison with Cuba is police violence. According to the FBI, U.S. police killed 1,232 people (a record number in more than a decade) in 2023, a quarter of whom were African Americans. Despite the lack of statistical transparency that many of us criticize the Cuban State for, and the continuous complaints on social media by opponents about abuses, violations of rights, etc., no one would believe that the Cuban police are even shooting at dangerous criminals, much less at dissidents. Curious paradox: lack of transparency and certainty, all mixed together.

This brief space is not enough for me to expand on the Cuban paradoxes, not even restricting myself to those in the political field.

The fair examination of Cuban political issues, the contradictory process of the reforms, relations with the United States, the migratory flow and its complex factors, the ups and downs of a civic culture lost in daily life, the decline in participation, the dynamics of a consensus crossed like never before by dissent, the agitation of the public sphere, and many other tensions inherent to the transition, fill common sense with perplexities.

This formidable field of problems becomes fodder for all possible interpreters, whether the leader of a jazz band or a priest, a filmmaker or the owner of an SME, a retired doctor or a novel writer. All of them can have more instant credit than political analysis, especially when it stops before these problems as before an opaque, inscrutable object, before which many resort to the simple formula of attributing everything to the same, repeated cause: “the ideology.”

I propose returning to that political and not merely ideological analysis in future rounds. I just want to note that the first thing, I believe, is to overcome the arrogance and the pretension of know-it-alls with which our problems and their causes are addressed, following the advice of the Ifá priests: “Be respectful of the differences between human beings to avoid unnecessary conflicts and disagreements.”

Of all the premonitions and lessons that the Letter highlights, in addition to warning about the rise of “false testimonies,” I stick with the one that says: “Ignorance makes a free man a slave.” Perhaps we are all trapped in the web of a political culture that has not changed enough.