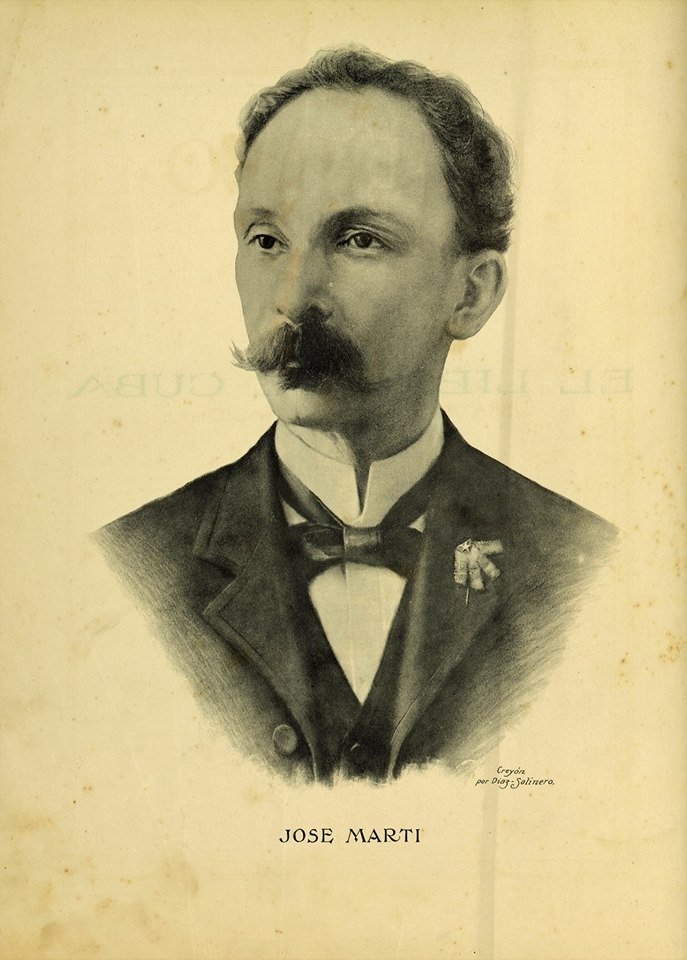

In February 1905 the statue of José Martí, which to this day presides over Havana’s Parque Central, was placed. A survey decided which figure should appear on that pedestal, which had previously been that of Isabel II.

For that celebration, the newspaper La Discusión published a series of vignettes. In one of them, the character of “El Pueblo”―later it will be “Liborio”―appears on the pedestal calling for a kind of “physical distancing,” so demanded during these days of COVID-19.1

Other vignettes allude to a problem that has even become more viral: the uses and abuses of Martí. In one of them, the Apostle appears saying: “The cordial republic…with all and for all.” In another, a trail of waste refers to so much discourse given on his behalf.

The phrase “With all, and for the good of all” has been discussed since it was said by Martí in a crucial speech given in Tampa,2 until today. So much discussion is not rare: it is the most radical phrase in the history of Cuba.

Since then, that speech―which has taken that phrase as its usual title―generated debates with veterans of the Great War. In 1910, the interested use of “with all, and for the good of all” was described as the “Jordan of the Republic.” In it, sectors once opposed to the Republic and its independence were “washing their hands” and in the new context enjoyed control over national power and wealth.3

In 1932, Abela’s character “El bobo” asked the Master: “Oh, but…did you say for all?” Our days are full of no shortage of calls to “contextualize” the phrase to specify who Martí was referring to and thus justify exclusions, or to use it for the opposite: to demand inclusions.

Given the diversity of uses of the phrase, it seems useful to return to the full content of that speech. Several elements are found in it, among them: the popular character of the republic, the prevention of tyranny, the plural composition of the people and human dignity’s place in its project.

Democratic republic vs oligarchic republic

One way to narrow the scope of the democratic version of republicanism is to limit it to an antimonarchical form of government, or, more contemporaneously, to a form of government that respects only limited institutional commitments.

In the context of Cuban independence, republicanism was not reduced to the monarchy vs. republic. It was impossible to be a monarchist and participate in an anti-slavery fight. It was impossible to be monarchical and independent. Nor was it just a form of government. It meant a political, social, moral program, a proposal for how to organize society.

Thus, the central dilemma took shape around which was the aspired republic.

Outwardly, the program of the democratic republic faced the reality of the “feudal and theoretical” republics born from Latin American independence. Also, it questioned the (first) Spanish Republic, which maintained the bulk of the colonial monarchical policy towards Cuba.

Fermín Valdés Domínguez approached this conflict: “…in this, as in everything, the hand of the Madrid government is seen, which has Weyler as an instrument in Cuba.… He says he is a Republican and is one of those who with the Phrygian cap proclaimed the Republic and the following day Alfonso XII was acclaimed in the streets of Madrid and the distinctive red was set aside for the tavern or the brothel.”4

Rafael Serra was consistent in defending the popular republic towards the interior of the independence camp: “Throw the despot out of our homeland; and also fight and win against their sick traditions; purify customs; give rights and full guarantee to women; abolish privileges…establish equality; spread knowledge, and preserve justice in all its grandeur.”5

Serra called those who defended this set of ideas “the extreme left of the separatist party.” It was the revolutionary camp’s radical bet. It is Martí’s bet.

The popular character of the Republic and the prevention of tyranny

Martí’s thinking about social wealth, honest work and the democratic functions that ownership must fulfill, elaborates a comprehensive defense of the people’s Republic.

Martí endorsed the “love of man to property acquired through the work of his hands.”6 In a text dedicated to Heredia—the exiled poet—, Martí speaks of land ownership as a common good: “that firmness of native soil, which is the only full property of man, and a common treasure that equals and enriches all, so that, for the crisis of the person and public calm, it should not be ceded, or entrusted to someone else, or ever mortgaged.”7

A reading cites comment by Martí on Herbert Spencer as the synthesis of his thought on socialism.8 In order to relate it to Marx, mention is made exclusively of “As he sided with the weak, he deserves honor.”9 However, there is another area of his thought, which is of interest to understand the proximity he maintained with socialist doctrines in his time.

Martí was consistent with this ideal: “he who depends on another to live is not free,” shared, from Aristotle, by a wide area of political thought. Cervantes, for example, placed it as being said by Don Quixote: “Freedom, Sancho, is one of the most precious gifts that heaven gave to men… blessed is he to whom heaven gave a piece of bread, without being obliged to thank someone other than heaven itself!”10

In this logic, the maintenance of a sphere of material personal independence is key in the political configuration of freedom. Martí clearly stated this: “The greatness of the peoples depends on the independence of individuals. Joyful is the land on which each man owns and cultivates a piece of land.”11

It is a classic ideal of republicanism. Nineteenth-century socialism made it its own, reworking it according to the needs of a context of industrial revolution. Marx defended it in Criticism of the Gotha Program: “…the man who has no other property than his own labor force, in any social and cultural situation, must be the slave of other men, of those who have taken over ownership of the objective working conditions. He can only work with their permission, that is, he can only live with their permission.”

Robespierre also did it in the middle of the French Revolution. It wasn’t necessary to be a Marxist or a Jacobin to do it. Paine and Jefferson also defended it. In the case of Martí, it was acknowledgement of the ideal of social democracy of his time. In Cuban Marxism, figures like Mella and Roa thoroughly understood that content of Martí.

The “Apostle” defended the distribution of property that would allow the “creation of many small landowners.”12 He exalted the “new abolitionists”―the 19th-century “progressives” in the United States―, “those who want to abolish private property in public assets.”13

He was close to the ideas of Henry George and celebrated other “apostles”: Swinton, Post and Powderly. These believed “that the nation, which is the name of the State of the guardian of common property, cannot give in dominion the land that belongs to all, and is necessary for all, but to be leased or loaned, and only for national uses.”14

Martí thus challenged the oligarchic connection between wealth and power―the structure of what he called the “Caesarian republic” in the United States. “Republic,” he said, “is the people with the worker’s tool (sic) on the right, and the freedom rifle on the left.”15

The Tampa speech is explicit about such content. He claims to set “the table of thought next to that of breadwinning,” and to close “…the way to the republic that does not come prepared by means worthy of the decorum of man, for the good and prosperity of all Cubans!”

Social democracy is not just about economic justice. It has political ends: individual, social and national freedom. It is a resource to prevent the tyranny―also republican and capitalist―of the concentration of wealth. Martí summed it up with great synthesis: “there is no other way to ensure freedom in the homeland and decorum in man than to promote public wealth. Property preserves the states. A despot cannot impose himself on a working people.”16

People’s diversity and its plural representation

In the Tampa speech Martí outlines a beautiful portrait of the Cuban people. It is also comprehensive of its diversity.

In that speech he mentions a “list” of social subjects that make up the people in the struggle for freedom. He names the veterans of the Great War, whose command habits are no less than the “admirable concert of republican thought and (of) heroic action”; to the many “who are barefoot”; the “generous black, the black brother”; the “Spanish who suffers, along with his Cuban wife, from the irremediable helplessness and the miserable future of the children”; to the “first martyrs (who) were men born in the marble and silk of fortune.”17

With a class perspective, Martí remembers how “this holy revolution” brought together, by the redeeming virtue of just wars, the heroic firstborn and the farmer without inheritance (and) the owner of men and his slaves.” It was an acknowledgment of the popular character of the war. From that war, as before the barracks, the Cuban people ended up being born.

This people was constituted through politics based on social, class, ethnic, regional differences. It was not divided by categories such as “grateful and ungrateful,” as it has been tried to establish to justify the tearing apart of who “we are all.” In fact, Martí demands protection, in that same speech, for the one who “…was born in the same land as us, even though sin upsets him, or ignorance misleads him, or anger infuriates him, or crime bloodstains him!”

If the people are plural, they must be politically represented in a different way. In such a search, Martí strongly contested the corruption of the vote, the dependence of the electors on the elected, and any other restriction of the independence of the voters. He was thus opposed to the rampant corruption of the vote―its buying and selling―but also to clientelism and factionalism. He thought that where there was freedom in voting, citizens voted, if on the contrary “today, when they see how the vote is marketed, they do not vote.”18

For the same reason, he was concerned with “ennobling” the suffrage: “Neither should the good rider let go of his horse’s reins; nor the free man of his rights. It is true that it is more comfortable to be directed than to be directed; but it is also more dangerous.”19 Martí found no remedy for the problem both in “creating new district organizations” and “in improving the voting mass”: “If today they disdain the exercise of their right as owners, tomorrow they will be terrified to prostrate themselves before a tyrant that will save them.” 20

Martí worried so much about the cleanliness of the vote that he proposed “casting the expenses of the elections on the public treasury”21 and to make the vote compulsory 22 as a civic duty. Informed, independent and self-organized voting was a channel for active political participation as well as a way of ensuring the collective government of “all”: “Only in the fact that suffrage is corrupted can there be the danger of the countries that are governed by suffrage: where there is no power superior to another….”23

Such a program―no power per se over another―is inscribed in Article 5 of the Bases of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, which “is not intended to bring to Cuba a victorious group that considers the island as its prey and domain, but to prepare, with whatever effective means the liberty of the foreigner allows them, the war to be waged for the decorum and the good of all Cubans, and to give the entire country the free homeland.”24

The dignity of all

Ana Cairo Ballester reconstructed the various republican influences on Cuban political thought. Specifically, she argued: “Perhaps [Martí] is the most fascinating personality to study the conjunction of what Cuban republicanism stems from.”

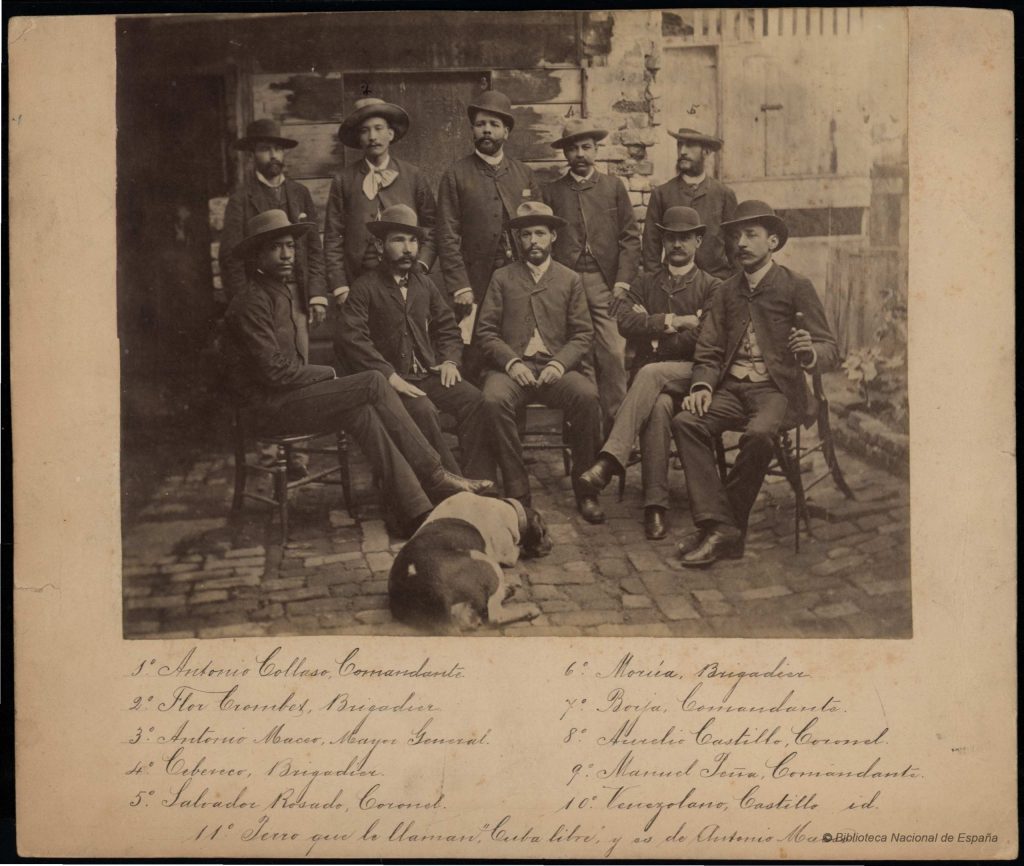

For Céspedes, Emilia Casanova, Agramonte, Maceo, Máximo Gómez, Rosa Castellanos, Guillermón Moncada, Valdés Domínguez, Rafael Serra, Diego Vicente Tejera, Isabel Rubio, Juan Gualberto Gómez, among the enormous mass of the participants in the war, struggled for the “democratic republic.”

That was Martí’s wager in Tampa: “I believe even more in the republic with open eyes, neither foolish nor timid, neither robed nor collarless, neither over-cultured nor uneducated, since I have seen, by the sacred warnings of the heart, together on this night of strength and thought, together for now and for later, together for as long as patriotism reigns, Cubans who put their frank and free opinion above all things, and a Cuban who respects them.”

Such a group is not reducible to a form of government. It is a compound of ideas and practices about revolution, democracy, freedom and justice. Roig de Leuchsenring cited, from Martí, the following as the “commitment that the Revolution makes: ‘She will be governed so that the vigorous and capable war will soon give a firm house to the new Republic.’”25

It was not an ideal defended only by intellectuals. The Cuban people, the main hero of the feat, made it its own. The “Cuban Enlightenment” was not that of the slave-owning sugar aristocrats: it was the popular subjects who re-elaborated the ideals of freedom, equality and fraternity for their context and their needs.

A text published in La doctrina de Martí is, among many others, an example of this. Its author, who through his prose seems a very humble person, presented Martí as “the enlightened one, the friend of the people, the apostle of the ideas of justice, democracy and truth.” The figure—added “Adrasto,” the author’s pseudonym—“sympathetic and admirable of Martí would not have existed, if he had not had as a pedestal an admirable sympathetic ideal.”26 That ideal was the Republic.

Sectarianism is always void of self-awareness. It is while proclaiming not to be. The idea of “with all…” is not directed at the “good,” the “grateful,” which always means “ours” for the respective sectarianism.

Adrasto placed in his text an inscription, signed by Martí, which said: “these are just the preliminaries of a great campaign, generous and active, after which the bad guys will not dare to be so much.” The “with all, and for the good of all” is so radical because perhaps it does not refer so much to the who―since it included even the “bad guys”―but to how we all are: it refers to the support of common coexistence among the free and the equal: refers to how to democratically process ownership, liberty, law and order and the political representation of the people.

That common order of coexistence had enemies then, and it has them now. However, it is a paradigm that is not afraid to face its exclusions―it understands them as legitimate, if they attempt against such an order―but concentrates on how to make it possible. Its core is how to produce the social, moral, institutional framework that makes it possible to live, among all and for all, in “full dignity of man,” that first law of the Republic, the pedestal on which Martí is erected in Cuba’s history.

Notes:

1 “Ladies and gentlemen, the Apostle has ceded me his position, for the moment, to tell you on his behalf to take these children home immediately, because he does not want the act of unveiling his statue today to be the cause of the discovery tomorrow, in those little creatures, of scarlet fever and measles.” La Discusión, 02.22.1905

2 “Discurso en el Liceo Cubano,” Tampa, November 26, 1891 (1991). In José Martí (Ed.): Obras Completas [Complete Works]. Taken from the second edition published by Ciencias Sociales publishing house, 1975, First reprint, 1992. Volume 4: Ciencias Sociales publishing house.

3 Brito, H. C. (C.L. Otardo) (1910): Breves consideraciones sobre el alcance que Martí quiso dar y dio a la frase “La República con todos y para todos.” Havana: Rambla y Bouza Printers.

4 Valdés Domínguez, Fermín (June 30, 1897): Patriotas y (¿repatriotas?). In La doctrina de Martí. La República con todos y para todos, June 30, 1897 (Vol. 1, New York, No. 28).

5 Nuestra labor. La doctrina de Martí. La República con todos y para todos, New York, July 25, 1896, Vol. 1, No. 1.

6 “Vindicación de Cuba,” OC, t. 1 p. 240

7 “Heredia,” OC, t. 5 p. 170

8 “La futura esclavitud,” OC, t. 15, p. 388 and ss

9 “Honores a Karl Marx, que ha muerto,” OC, t. 9, p. 387 and ss

10 I owe this reference to Antoni Doménech Figueras.

11 “Guatemala,” OC, t. 7, p. 124

12 “Reflexiones destinadas a proceder a los informes traídos por los jefes políticos a las conferencias de mayo de 1878,” OC, t. 7, p. 167

13 “La conferencia americana,” OC, t. 6, p. 64

14 “Nueva York en junio,” OC, t. 11, pp. 18-19

15 “Club político de Ocala,” Patria, April 3, 1892. On that horizon, he added: “Exclusive wealth is unfair. Be it of many; not from upstarts, new dead hands, but from those who honestly and laboriously deserve it. A nation with many small landowners is rich. The people where there are some rich men is not rich, but the one where each one has a little wealth. In political economy and in good government, to distribute is to be successful.” “Guatemala”, OC, t. 7, p. 134

16 “Carta a la República,” OC, t. 8, p. 27

17 Regarding women, however, he repeated contents present in his work, in which he reserves them for motherhood, care and prudence.

18 “Carta al Director de ‘La Opinión Nacional’,” OC, t. 14, pp 509-510.

19 “Carta al Director de ‘La Opinión Nacional’,” OC, t. 9, pp. 105-106.

20 OC, t. 10, p. 43.

21 “Carta al Director de ‘El Partido Liberal’,” In “Otras Crónicas de Nueva York.” Center for Martí Studies. Ciencias Sociales publishing house, Havana, 1983, pp. 132-133

22 “Las elecciones del 10 de abril.” From “Patria,” New York, April 16, 1893, OC, tome 2, p. 296.

23 “Carta al Director de ‘La Nación’,” OC, t. 10, p. 123

24 “Bases del Partido Revolucionario Cubano,” OC, t. 1 p. 280

25 Roig de Leuchsenring, Emilio (1957): El Manifiesto de Montecristi, sus raíces, finalidades y proyecciones. Havana: Office of City of Havana Historian.

26 Adrasto (Vol. 1, No. 9, 1896): “La guerra, Martí y la República.” In La doctrina de Martí. La República con todos y para todos, Vol. 1, No. 9, 10/11/1896.