Help us keep OnCuba alive here

In 1909, in Camagüey, a U.S. citizen refused to attend to a “colored” Cuban. The event, which generated public discussion, took place in a barber shop open to the public. The report on the case affirmed that “whatever concerns exist in the United States, regarding the differentiation of races in the social order, those concerns, which undoubtedly have also existed among us as painful reminiscences of slavery, have been disappearing….”1

The report cited as causes of this disappearance the “gradual but effective” result of the Cuban wars of independence and the development of the culture of the so-called “colored race.” Such a “race,” both by “mandate of law” and by its “personal effort,” would have achieved “access to the highest positions in the Republic, based on equal rights in relation to other citizens.”

Another act committed by an American, former police officer Derek Chauvin, has now sparked great discussions in the world, also among Cubans, about the legitimacy of the forms of protest, as of the murder of George Floyd in the United States. Ironically, some of the expressions from that distant report also appear in the discussions of the present.

On the social media, we have seen compatriots—identified with the “hard exile” in Miami, but not only—questioning the protests against Floyd’s death, demanding exclusively peaceful forms of response, and ensuring that African Americans should take advantage of the exercise of their rights and apply themselves with greater effort to enjoy the possibilities of improvement and social advancement that American capitalism would provide.

Racism has its history and particularities in every context, but it is a global phenomenon that has shaped the world in which we live. For the analysis of that world, as Stuart Hall has said, race is not a “subcategory.” Rather, it structures a “total social formation that is racialized.”

Cuba has its history with racism and its forms of protest. Part of the criticism of the reactions to Floyd’s death also has a history among Cubans.

Personal effort and civil disobedience

José Proveyer was a young Cuban, a university student, who practiced journalism. For his family, and for the social environment in which he lived, his career represented the hope of inclusion and social advancement through professional training. His anti-racist activism involved the peaceful struggle in favor of Cuban blacks’ intervention in the life of the country.

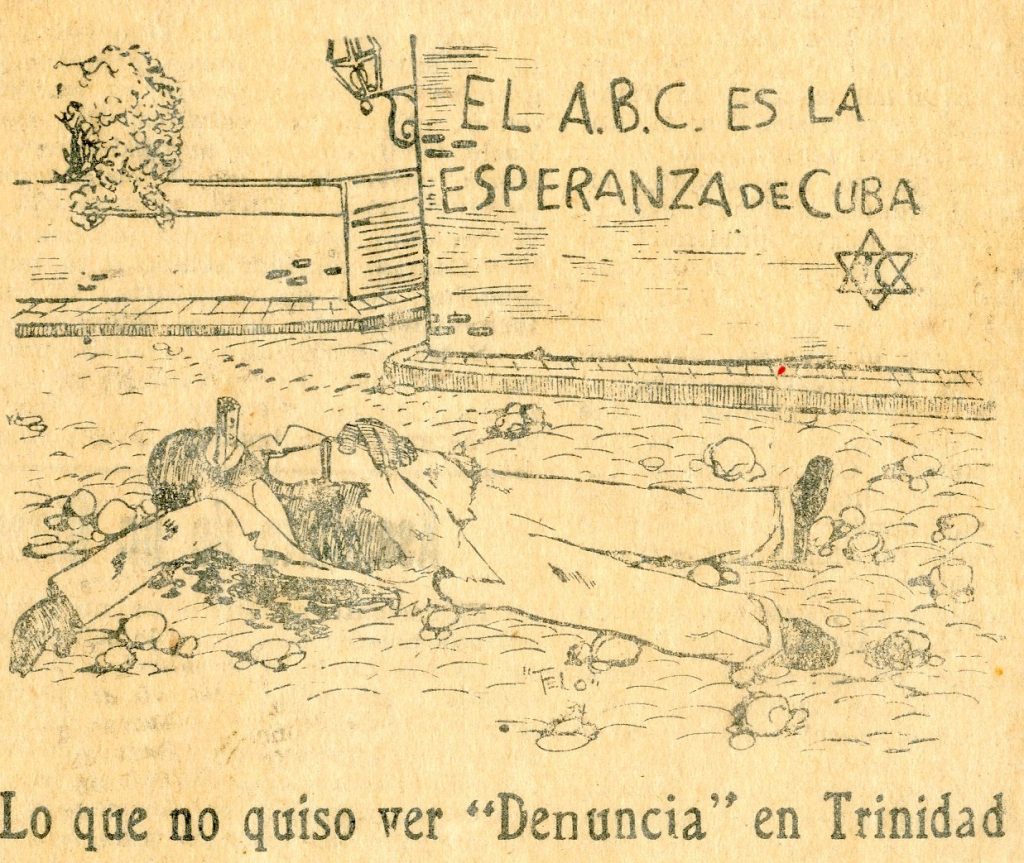

Proveyer was a “mulatto,” a racial hierarchy “higher” than that of blacks in Cuba at that time, which maintained exclusive “mulatto” societies, forbidden for blacks.2 In 1934, in an act of vindication, together with a group of “colored” people, the student “invaded” the white area of the park of the city of Trinidad.3 As a consequence of the brawl the act generated, Proveyer was lynched.

His crime was crossing the “color line” of a park. He had not set fire to a sugarcane field, looted, or stolen.

Certainly through his personal—and collective—effort, a significant number of Cuban blacks and mestizos had managed to become, by that date, professionals, businessmen, and organized workers. However, racism remained a daily affront. Days after Proveyer’s murder, several of those who had lynched him attacked one of the black Cubans who had protested the student’s death.

Proveyer’s “personal effort” collided with the ironclad limit of the place—physical and social—reserved then for Cuban blacks. It didn’t matter that Proveyer practiced a non-radical way of protest: peaceful civil disobedience. An illustration representing his death shows him being forced to swallow a newspaper, that is, his anti-racist voice.

Social justice and racial protest

The Independent Color Party (PIC) represented, like no other Cuban political party in the first two decades of the 20th century, the demands of Latin American popular nationalism.

Betting on “the popular” against an oligarchic state is a radical challenge. PIC’s nationalism understood that the “popular” in Cuba was classed by race. They observed that they were excluded as poor as well as black.

They understood that being black was a substantial condition of the origin and maintenance of their poverty.

The PIC reacted to the exclusionary nationalism that the possible framework of protests in Cuba presented in this way: (need) “Nothing as black: everything as Cuban.” In 1912, the newspaper El Triunfo put it this way: “Here in Cuba it is not said that ‘the best black is the dead black’ (in reference to a U.S. saying); no, here in this land fertilized with the blood of its heroes what is said is: “He is the best black, the most Cuban black.”4

Before saying that it is a good idea, it is necessary to explore what it hides. Hubert de Blanck composed a Hymn to the Republic, dedicated to José Miguel Gómez when he won the presidency (1908), which states: “All of Europe and America applauds and at the same time the United States/your children who divided yesterday/are joined today by brotherly love.” 5

Cuban popular music collects in various ways the 1912 massacre. Researcher Yorisel Andino mentions the following themes: by Juan de la Cruz, “Estenoz e Ivonnet”; by Pepe Sánchez, “Ivonet”; and Manuel Corona, “Ivonet y Estenoz.” (Transgressive discourses: breaks in the Cuban musical canon, Santiago publishers, 2015.) As Cristóbal Díaz Ayala has said—in personal correspondence with the author of this text—, mentions of 1912 are used as intertextual quotes in several songs. The best known of these quotes are those referring to La Maya and Alto Songo, which can be found, for example, in Antonio Machín (“Fuego en La Maya”), the Septeto Nacional (“!Mamá, se quema La Maya!”); the Conjunto Chappottín with Lilí Martínez Griñán (“Alto Songo”)—with versions such as that of Johnny Pacheco and Pete El Conde Rodríguez—, etc. By courtesy of René Espí Valero, the song “Ivonet y Estenoz,” a clave by Miguel Companioni (Cuarteto Nano with guitar, Odeon Record A 88000) is reproduced here, perhaps for the first time. I appreciate the generosity of Espí Valero, one of the most diligent scholars of Cuban music, for giving this piece from his personal collection to accompany this text.

The PIC reacted against this notion of racial brotherhood, which unified everyone within the homeland, but left racialized inequality intact. According to the PIC, “there are phrases [“nothing like black….”] that have killed the just and legitimate aspirations of the black element to the point of having cowed it in such a way that it feels incapable of claiming what in fact and right corresponds to it.”6 For its members, they were both black and Cuban. There was nothing antagonistic about both identities.

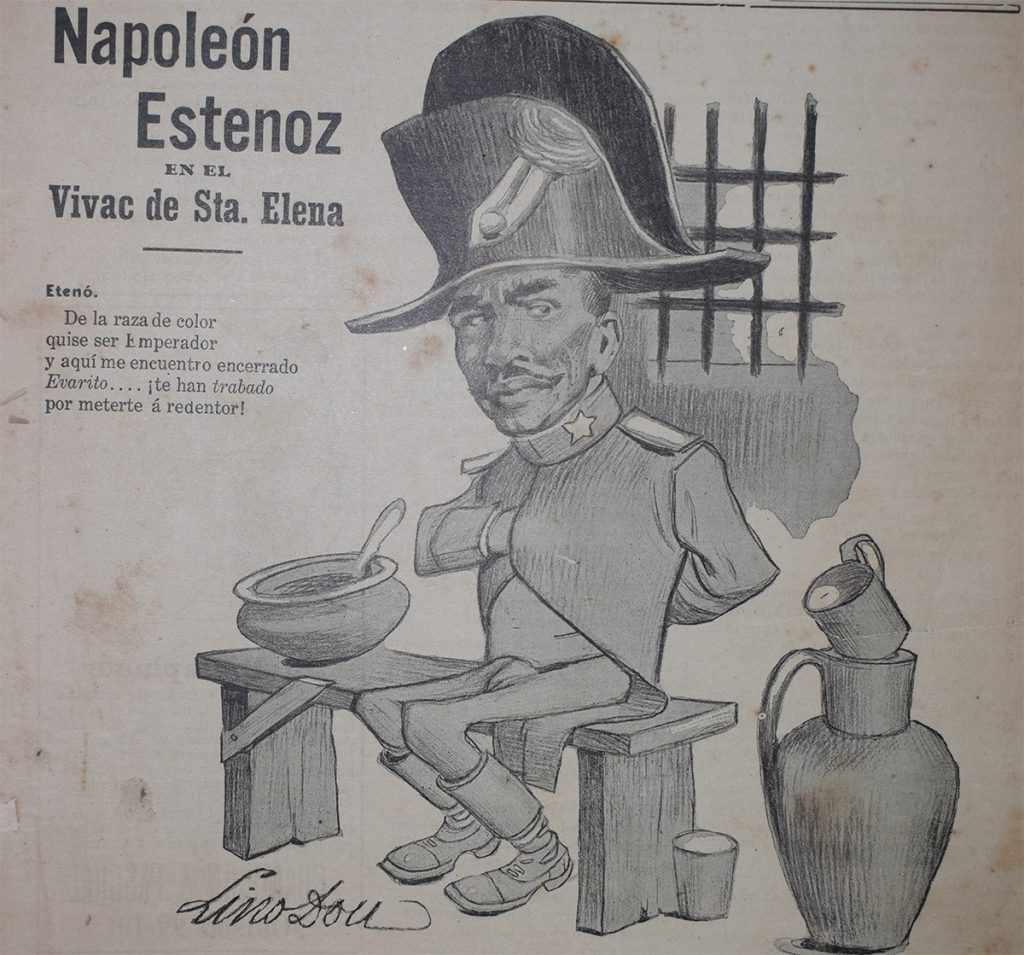

The PIC launched into a (badly) armed protest in 1912. In 1910 several of its members had been subjected to a legal farce for an alleged “black conspiracy.” Before, they had been cannon fodder in the 1906 “revolution.” Before, they had integrated a very powerful interracial army, which had challenged the racist notions established at the time, both in the United States and in Spain.7

Its uprising in 1912 took place on May 20, to denounce their exclusion from the Republic, which many of its members had decisively contributed to founding. The protest was put down by a very violent state crime, which until today is still only known as “la guerrita del 12”, or the “war of races.” That same State had previously closed the doors to the self-organized political participation, by legal means, of Cuban blacks against their exclusions from their interests and needs.

A Cuban hip hop song: Obsesión, “Furé en Talla,” with mention of Estenoz and Ivonet.

Alliances and differences within anti-racism

For many in their respective times, both forms of protest, that of Proveyer and that of the PIC, were classifiable as “black racism” due to a logic perhaps similar to what is now called “reverse racism,” which would be a kind of “anti-white racism.” However, such a thing is not noticeable in their ideas or their actions.

Cuban anti-racist struggles have resorted to diverse means, but they have in common that on very rare occasions they have defended some type of hierarchical supremacy of “blacks” over “whites.” Gustavo Urrutia, who defended the legal means for the advance of anti-racism―along with demands for social justice―, did not do so. Neither did the PIC.

This tradition has a great plurality of approaches and contradictions among themselves. Such diversity makes it very powerful.

During the final phase of Independence, both Juan Gualberto Gómez and Rafael Serra defended the need for black self-organization to achieve social improvements and anti-racist advances.

The Central Directory of the Societies of the Color Race, led by Juan Gualberto, or La Liga society, created by Serra, sought the integration of blacks and mulattos in Cuban society. But this did not happen without differences between them. In a text published in La doctrina de Martí, directed by Serra, it can be read that Juan Gualberto had edited in Patria a text “where the color class cannot be further insulted.”8

José Martí was a close friend of both and celebrated their outstanding participation in the war. Over time, Martí and Serra would become very close references of the PIC. Juan Gualberto, on the other hand, would be one of its critics.

For their part, Antonio Maceo and Martín Morúa Delgado shared the blacks’ social integration program, but did not believe in the usefulness of separate black organizations. Maceo is the consensual leader of Cuban anti-racism. Morúa is a very controversial figure.

In turn, Juan Gualberto and Morúa maintained conflicting positions. However, an anti-racist communist, Salvador García Agüero, not suspected of being a “traitor to his race,” dedicated these verses to Morúa: “(…) Worthy tributes to your just glory/, your race and history owe you the same/, the offering of bronze, the rhythms of an estrus/, and the clear prestige of illustrious laurels./ I hope they were faithful disciples/all who once called you Maestro!”9

The PIC, outlawed through an Amendment by Morúa Delgado, did not see eye-to-eye with Juan Gualberto either. For the PIC, Martí’s friend was “as always, inopportune,”10 for reasons similar to those put forward by Lino Dou,11 although he considered himself a disciple of the independence hero.

For his part, Pablo de la Torriente praised these words of “old man” Souza: “First of all… Juan was a man who always, with more or less intensity, was on the side of the spirit of freedom. Later, he was a true vindicator of the rights of his race.”12

The mainstream press lashed out in other ways, and very frequently, at Juan Gualberto.

Over time, anti-racist intellectuals, such as Juan René Betancourt and Sixto Gastón Agüero, were inclusive in recognizing the usefulness of that plural tradition.

For Betancourt, there was “no choice but to declare that from the colony until present day (the 1950s), four men have been the most conspicuous defenders of their race: José Antonio Aponte, Antonio Maceo, Juan Gualberto Gómez and Evaristo Estenoz.” In this, “Juan Gualberto Gómez was the best theorist in this matter” and Estenoz was “the most distinguished of the leaders that men of color have had in republican Cuba.”13 For Gastón Agüero, “the last integral anti-racist current” had died with Morúa (1910), a current in which he also placed Martí.14

Seeing what has been seen, it is not convenient to simplify plurality or erase differences within the Cuban anti-racist tradition.

Rather, it is important to recognize how this diversity has several keys in common: justice is the supreme value; the legitimacy of the protest against racism is directly proportional to the severity of the exclusion it generates and the means available to deal with it; personal effort alone is incapable of modifying the structural conditions of racism; it is not pertinent to “dictate” to others the conditions in which they can protest; and Cuban anti-racism has considered as legitimate a great plurality of forms of struggle, ranging from education to radical protest, going through the class demand for economic inclusion.

Racism is not a vestige, it is a problem here and now

We Cubans have been hearing for more than a century that racism is a “vestige,” a “reminiscence” of the past. During the Republic born in 1902, it was said it came from slavery. After the 1959 Revolution, it has been said that it comes from that Republic, as well as from slavery.

This is what that 1909 police report says and is quoted in the note presented by the “National Program against racism and racial discrimination” last November.15

Cuban capitalism produced and reproduced racism born with slavery. Socialism, after 1959, profoundly transformed its conditions of possibility, both structural and cultural, but it is far from having made it disappear.

Racism continues to be produced and reproduced here and now: it maintains its differentiating uses in today’s Cuba in the social and police treatment of people, in access to housing, universities and property, in the profile of emigration and the reception of remittances, in the preference in thriving areas of the economy―be they state or private―, in the predisposition of school dropout rates and the prison population, in the unequal recognition that black Cubans members of the Liberation Army or the Rebel Army receive, and in the very ignorance about so many black members of the great Cuban anti-racist tradition.

Anti-black racism is, as Fernando Martínez Heredia argued, a constitutive element of Cuban culture. It is not an exclusively “cultural” problem, but it passes through the composition of the Cuban nation and people. Even with profound differences, it has been and is a crucial problem for the nation, the republic and democracy in the country. The debates around the protest for the death of George Floyd remind us that every time it is becomes too late to recognize it as a national problem, be it the Cuban community in Banes, Miami, or Barcelona.

Help us keep OnCuba alive here

***

Notes:

1 “Las razas ante las leyes y las costumbres de Cuba. Un caso de discriminación en Camagüey” (1938). Estudios Afrocubanos. Revista semestral (Vol. 2 No. 2), pp. 104–107.

2 The chronicles of the time I have been able to consult present him mostly as “mulatto,” although some refer to Proveyer as “black.” For example, here: “Alcemos nuestra más enérgica protesta contra los linchamientos de Trinidad” (1934). Juventud Obrera. February 8, p. 6

3 “Son agredidos los negros en distintos lugares” (1934). Bandera Roja. Órgano Central del Partido Comunista de Cuba (Year 2. No. 14).

4 “Antes que todo, cubanos” (1912). El Triunfo, 05.29.1912.

5 Hubert de Blanck, “Himno a la República,” In: Roa García, Raúl (2006): Bufa subversiva. Havana: La Memoria publishing house, Pablo de la Torriente Brau Cultural Center, p. L.

6 “Negros y cubanos.” Previsión, 07.04.1910.

7 See Ferrer, Ada (2011). Cuba insurgente. Raza, nación y revolución (1868-1898). Havana: Ciencias Sociales publishers.

8 Serra Montalvo, Rafael (1907). Para blancos y negros. Ensayos políticos, sociales y económicos. Havana: El score printers, p. 89

9 García Agüero, Salvador (1936). “A Morúa.” Adelante 1 (June 13).

10 “La conferencia de anoche en el club benéfico.” Previsión, 05.03.1910

11 “In short, we have nothing to lose because what we should have won has been denied us and by convincing ourselves that by practicing the doctrines of Juan Gualberto Gómez—which until now has wanted nothing for the black separated from the white—we would have to wait for the establishment of our rights a term equal to that of the arrival of the Messiah for the Israelites.…” Dou, Lino (1909). “Derrotero obligado.” Previsión, 11.05.1909.

12 De la Torriente, Pablo (2016). “Un muerto explotado y olvidado.” In Pablo en Ahora. t. 2. Havana: La Memoria publishing house, Pablo de la Torriente Brau Cultural Center, pp. 163–164

13 Betancourt, Juan René (1955). Doctrina Negra. La única teoría certera contra la discriminación racial en Cuba. Havana: P. Fernández y Cia, pp. 72–74

14 Gastón Agüero, Sixto (1959). Racismo y mestizaje en Cuba. Havana: Lid, pp. 224–225

15 Leticia Martínez Hernández: “At the meeting of the Council of Ministers, the National Program against Racism and Racial Discrimination was presented, which has been designed ‘to combat and definitively eliminate the vestiges of racism, racial prejudice and racial discrimination that remain in Cuba.’”