Several years ago, I was invited by television director and documentary maker Juan Pin Vilar to a program on the Cubavisión Internacional channel, to talk about the promotion of electronic music and other aspects in Cuba. I told him that it was a controversial issue and that he could not leave anything out or overlook pioneering festivals of this genre such as the late Rotilla. He told me to say what I thought, that the hard core of the conversation would be included in the edition.

Indeed, when I saw the broadcast of the program, I was surprised that the most important part of the exchange had aired. I was very satisfied with his work as director and scriptwriter of the space.

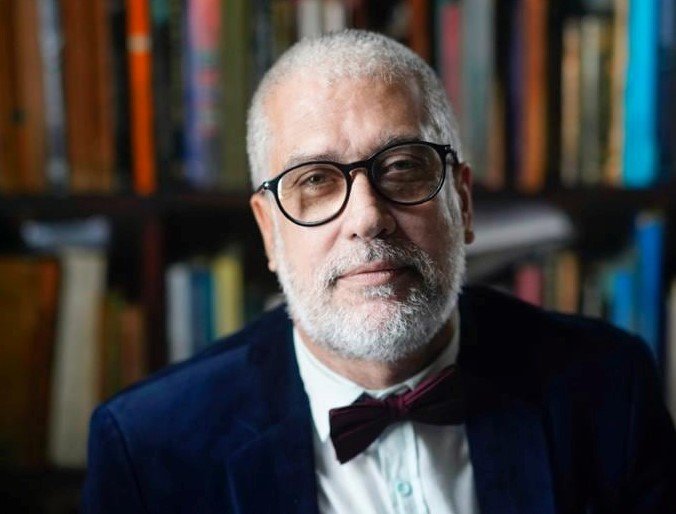

Juan Pin no longer works in Cuban television (nor do I in the Granma newspaper). He is promoting his career as an independent filmmaker and continues to direct works that he considers to have something to contribute to the cultural diversity of the country (I now work for OnCuba).

Juan Pin Vilar’s career has always been surrounded by controversy. He is someone who says what he thinks and that has brought him more than one confrontation in various spaces of culture and communication in Cuba.

He has been closely linked to various exponents of the Nueva Trova and music in Latin America. He is very close to Pablo Milanés, Fito Páez, and was Francisco Céspedes’s manager for many years. He has played a fundamental role in the organization of the Fito and Pancho concerts in Cuba. I remember that on one occasion I interviewed the Argentine thanks to his intervention. Fito was surrounded by friends and musicians, in one of the dressing rooms of the Karl Marx Theater, and he received me to speak briefly about his return to Havana and the affections he shares with the Cubans.

Juan Pin believes in peaceful demonstrations as a way to defend causes that he assumes just. That is why he participated in the recent convocation of Cuban artists and intellectuals who gathered in front of the Ministry of Culture (MINCULT). What initially attracted mainly young people later became a meeting where Cuban artists of different generations met because they had something to say and they felt that the cause could also be theirs.

The protesters demanded to speak with Minister of Culture Alpidio Alonso, to present their concerns and annoyances about the barriers that, in their opinion, prevent full creation on the island, and the development of Cuban society. Finally, after almost 10 hours, a group of 30 artists was received on behalf of the rest. They met with the deputy minister of culture, Fernando Rojas. In the exchange, Juan Pin talked to these young people and other established figures such as director Fernando Pérez and actor Jorge Perugorría.

“From a very young age, I have participated in almost everything that summons me as a Cuban. That’s why I always say that in these struggles I am summoned by Cuba and the creative avant-garde, which is generally young,” the filmmaker tells OnCuba.

In recent days, the media have referred daily to the demonstrations in front of the MINCULT and one of the triggers that sparked the protest: a group of young people grouped in the San Isidro Movement (MSI) went on a hunger strike to demand the release of rapper Denis Solis, member of the collective, sentenced to eight months in prison for contempt.

I ask Juan Pin his opinion about the meeting that took place on November 27. “Without a doubt, it is historical,” he answers sharply.

Some media have described as unprecedented this fact that today occupies the center of the Cuban cultural and political debate. In previous years, other events with a certain similarity have put the center of Cuban culture in tension. The so-called email war (2007) is still fresh in memory, a strong cultural controversy born from the appearance on television of two figures directly related to cultural censorship in Cuba in the 1960s and 1970s.

Unlike other similar events, social networks had a great weight in the organization of the 27N meeting. This platform is used more and more frequently by Cubans to express their social unrest, as well as by activists for various causes who have joined to demand their rights, as is the case of the LGBTIQ+ community.

Juan Pin explains why for him it was historic. “A group of anti-establishment artists has common points with a mass of creators, not only young people, but from different generations, to sit down and talk with an institution that has never wanted to accept its existence. That is a historical and unique incident within the Cuban cultural and intellectual spectrum. It has never happened since 1961, when the meetings at the National Library took place. It has all possible validity; otherwise, I would have refused to actively participate and would have focused on being a mere spectator. That is why I am very grateful to the young people who included me in their agenda, as one of their brothers.”

Juan Pin is 57 years old, has three children and several short films or teleplays that have not been shown on Cuban television. He has already learned to live with the silence towards his work, which has led him to seek other ways of inserting himself in international cinematographic circuits. During his career, he has been the protagonist or witness of stories that he intends to capture one day in black and white, as he has told me during some of our conversations. Today, without a state job, he writes for various independent media. A week ago, he published a collection interview with singer-songwriter Carlos Varela on the Diario de Cuba site.

He has always had close contacts with the youngest filmmakers and artists. Despite the generational gap that separated him from young people who were mostly under 40 years of age, he affirms that he felt comfortable in the demonstration. “I felt comfortable, calm and smiling. I did not personally know most of the young people, but the maturity of their proposals, the language they used, and the infinite love for Cuba, that diverse Cuba that we love and in which we all fit, struck me. The conversation took place in a polite, frontal climate, with antagonistic positions and respect for each one’s opinion. Those kids, without exception, were great. Listening to them meant a hope that Martí’s Cuba is possible.”

I do the interview with Juan Pin on WhatsApp. I believe that at this moment it is a win-win situation for both of us, in order to gain time to try to explain a little or deepen this moment of relevance for Cuban culture, that universe that is experiencing an unexpected shake by the entry into play of unresolved questions that remained latent on the margins. I intend to collect testimonies to delve into this stage that, for some, may be a watershed due to the diversity of cultural actors and their demands. Several of the people with whom I have spoken converge on the need for this debate to contribute to a more open and participatory cultural system. More democratic. Others are unmarked and prefer to remain as spectators away from the line of fire for their own reasons or value judgments that I also recognize as valid.

For him, this type of debate must be held based on respect and freedom to confront ideas…of understanding. “Without false leaderships or vain pretenses. The around 300 people who were there did not belong to the institutional agenda or that of the 27N…they were there because during the year there has been a lot of violence in different social groups, for different reasons, and San Isidro was one of many. That must stop. The 300 are united by the hope that any conflict must be resolved with understanding, and each party or all parties must yield for the dialogue to advance.”

Juan Pin was practically born in the Cuban Institute of Radio and Television (ICRT). He knows the inside of the institution by heart. He keeps pains, wounds of the private and professional and satisfactions. “Satisfactions, all of them, even those that I owe to the effort of the team I worked with. Finishing a work in the conditions of mediocrity and exclusion that have been seen in the ICRT is a feat. Dissatisfactions, many. Knowing and feeling that there is a hard chicanery so that people like me are unable to work.”

These are harsh words, but they are backed by the work of a man who for decades lived devoted to the ICRT. On different occasions, I have spoken with journalists or announcers about the work of Juan Pin. Everyone recognizes him as a polemicist and emphasizes his qualities as a human being. “He is a good person,” they say.

This filmmaker has entered dark areas of Cuban culture and has openly criticized the society in which he lives, in accordance with his personal dictates. He is, for many, a credible person. Maybe that’s why he was in the group that led the talks. “For me, there are no limits in dialogue, but I am one in 30, plus two (Fernando Pérez and Perugorría). In a dialogue, if it is good and advances, the limits are stretched until they disappear and become a whole. That takes time and maturity. In my case, independence and sovereignty are not negotiable, because they are not abstractions, they are processes of building our nation. They are always in danger and it has cost blood and thought to win them.”

The documentary maker was particularly struck by the spontaneity of the young people. “I was moved by the freshness of their ideas, the impetus and the commitment to themselves and their time. Intellectual sincerity. Ease. The work.”

He was not in the second meeting held between a group of artists and cultural officials, led by Minister Alpidio Alonso, after the dialogue with the group of 30 was initally broken, which set the presence of Cuban President Miguel Díaz Canel as a condition, in an email sent to the institution. In the days after the 27N exchange, several artists and participants have denounced harassment in the networks or discredit in the media. Juan Pin believes that the MINCULT should intervene so that artists can express themselves freely, without the influence of an external political agenda that puts the sovereignty of the country in check.

“Freedom of expression must be discussed and that no one can be criminalized for their work. Whoever commits to a cause is the citizen, not the poet or the filmmaker, even if they develop, whoever wants, a committed work. The poem cannot be repressed or criminalized. Citizen owe themselves to the laws. If they do not comply, let them be tried with the guarantees offered by the Constitution and with those that are lacking as well. When the police or security forces act based on a poem, a film or a painting, they are violating their functions. The MINCULT must not allow this interference, which exists and is common. They must accept that there are independent artists, who do not want to belong to either the UNEAC or the Hermanos Saíz Association…. And the independents must separate themselves from any political agenda that represents loss of independence and sovereignty. Also, as is my case, I cannot agree with the economic aggression that the blockade implies. When both parties understand this, which are principles, then a dialogue will take place. I have never accepted any tutelage, least of all from the government of the United States.”

Juan Pin believes, like many of the artists and intellectuals involved in the debates, that dialogue is the most effective way to solve conflicts. “You have to recognize the existence of independent artists and spaces. Because from the moment they went to the institution, they were accepting it. Also, tolerance of those who are opponents because everyone does not have to like the government, much less the government’s political agenda. Above all that, there must be a respectful dialogue, avoiding interested agendas from abroad or from the different groups or criteria of power that make up our government. Nor is it fair that the repressive forces attack in such a disproportionate way the citizens that want to express themselves, because before artists, intellectuals, opponents, engineers and filmmakers, they are citizens.”

The director draws a bridge between dialogue and love. He believes that the momentum for generational change has always been the same, but the only thing that has changed is the contexts. “In that, the generations are all the same, only the rules of the game and the context imposed by the time change. Romeo and Juliet loved each other. The young people who were in front of the MINCULT too. The generation that triumphed in 1959 had motivations similar to ours: freedom, democracy, sovereignty, and independence. I don’t think those who have an agenda interested in something else, or that leads to another phenomenon, will succeed. The more you study, read and deepen the processes of cultural and social emancipation, you will be more prepared for these types of encounters. But young people are not stupid and, for the most part, those I saw are better prepared than I was in previous debates. It is important that society generates thought and ideas to build a more diverse Cuba. A dialogue can contribute a lot in this regard.”

For you, what is the definitive solution to channel the demands of new generations of artists?

“That their work not be controlled. That they be allowed to finance themselves and not criminalize them so much. Life decants talent, trade, according to the result of the work. There are too many tables and there is no space for the auditoriums. Nobody from a position is authorized to qualify me as an artist; only my work,” concludes Juan Pin.