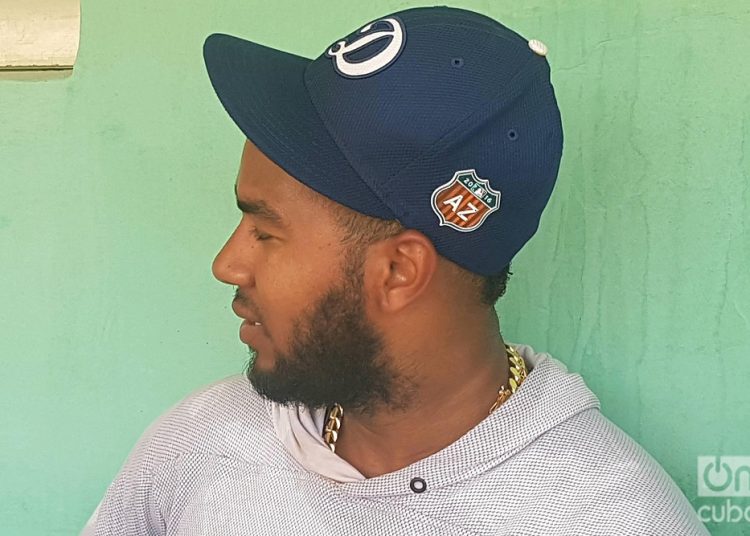

Bárbaro Erisbel Arruebarruena Escalante (Abreus, 1990) wears a Los Angeles Dodgers cap with the logo of the Arizona Cactus League, where he once fought, without much luck, to ascend to Chavez Ravine Hill.

Two huge gold chains hang from his neck; there are no traces of the extravagant necklaces he used in the past. In the spikes, red and blue, you can see the number 1 and the Cuban flag.

One of Arruebarruena’s gloves has golden trimmings, although the most striking is the intense blue that contrasts with the red that dominates the Victoria de Girón Stadium, in Matanzas.

At first glance, the splendid whole and the figure of Arruebarruena itself don’t fit in the old Cuban baseball field, lacking in splendor and colors, but that, clearly, doesn’t matter to him.

“I’m neither the one who left for the United States nor the one who played in the Major Leagues, I’m one more Cuban,” says the shortstop from Cienfuegos, who lets us see that there is no reason to draw a dividing line with the repatriates: they are like any other Cuban.

***

It’s at noon and Arruebarruena hasn’t yet left the field. He has taken longer than usual to start training. First an interview, then he eats something ― he’s a type 1 diabetic at 29―, then he rests, drinks water and lastly goes to the field, when all the Matanzas preselection is challenging the May sun, which in Cuba is as hot as if it were summer.

Contrary to appearances, Arruebarruena is not lazy. Sometimes he gives the impression of playing at half speed, not trying, but in reality he has a gift.

“I’ve learned to deal with being told that I don’t play hard, that I’m not explosive, that I don’t give my all…. Many have told me so. I was born with the gift of playing baseball and doing things without making a 120% effort, but that doesn’t mean I don’t work,” says the shortstop to OnCuba.

In fact, Juan Miguel Vázquez, his partner for years in Cienfuegos, says that “El Grillo” is a machine. “After training, he looked for a box of balls and told anyone to give him rolling pitches, lots of rollings. Batting practices didn’t excite him too much, but fielding in shortstop drove him crazy. I’ve never seen anything like that before.”

***

On December 19, 2018, the Cuban Baseball Federation and MLB signed an agreement with the idea of normalizing the influx of Cuban players to different professional circuits. A new window of opportunities was opened for the players residing on the island, and also for those who were outside and wanted to return.

When it was learned that Arruebarruena would be back in Cuba, with intentions to play in the National Series, many thought it was due to the agreement, but in reality it was not like that.

“In principle, that Cuba and MLB signed didn’t influence my decision. After all, if I wanted to play in the Major Leagues, I was already there and could keep trying, even if it was not in the Dodgers. I had other offers and I thought about a change of airs, but in the end I gave up.”

So, why did you return?

I left with one purpose: to play the best baseball in the world. However, the process in the United States didn’t end as I expected. Diabetes drove me crazy, and I just thought about spending a quiet time with my family, enjoying time with my children. After almost a year without playing, I then decided to come to Cuba.

Why Matanzas and not Cienfuegos?

The first thing I did when I came to Cuba was go to my province to speak with commissioner Liván Angarica. He told me that I had to go to Immigration and put all my papers in order to then evaluate the possibility that I could play. He also told me to ask for the guidance of Pavel Quesada and Edwin Vassel, who had already gone through that with a thousand problems, because they had spent almost a year without being able to play.

After that, I didn’t go to see anybody else from the baseball leadership in Cienfuegos, I felt they had no interest in helping me and again making me a part of the team.

But you wanted to be there?

How can I not want to play with my province? I live behind the stadium, there I’ve all the comforts, but with the precedents of Pavel and Edwin, I think the same thing was going to happen to me.

In addition, all teams want to win, and to win you have to look for variants. For example, if a proven player arrives willing to reinsert himself, as a leader you should try to help him a bit, not let him try his luck with bureaucratic procedures. I felt that this was what was going to happen to me in Cienfuegos.

It hurts to say these things, because that is my province, where I was born, but I can’t understand that attitude.

And the idea of Matanzas, where did it come from?

I think they are random things. Armando Ferrer found out about my situation almost by chance and immediately approached me. He began, along with me, all the paperwork. He took my case to the commissioner, to the INDER leaders in the province and he helped me as much as possible with all the steps so that I could play.

Neither Ferrer nor anyone here in Matanzas knew me, because I had never had ties with the province, but despite that, they tried hard to bring me here. After those people took the step and helped me, now I won’t let them down.

***

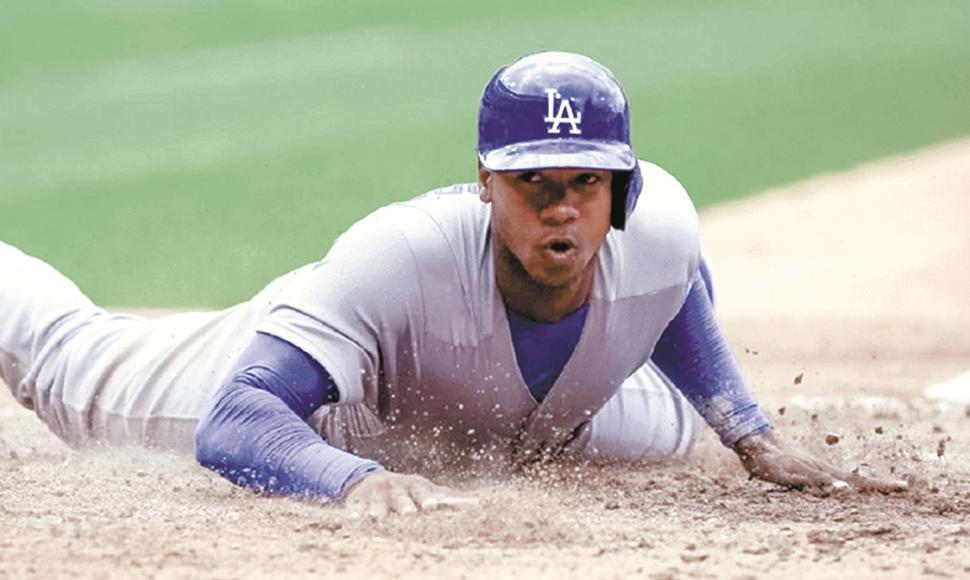

On July 24, 2018 Arruebarruena was let go by the Los Angeles Dodgers. In four years with the organization, he played less than 200 games at all levels, which is a joke in a baseball that accumulates more than 140 games in just one season.

When he talks about the subject, the Cienfuegos player doesn’t avoid a word: frustration. “I collected my money, I was there, I bettered myself, but I didn’t meet the goal, which was playing ball. It’s frustrating, and it was much more so after learning about my diabetes. I couldn’t believe it. How I a guy with my physique could have diabetes.”

Did you think about not playing anymore?

For a moment, yes. It doesn’t matter that you have all the money in the world, you are sick in a country that is not yours. There was no problem to live there, because I had my family nearby, they helped me in everything, but playing is something else, you need support in the world of baseball, and that is harder to find.

But, when diabetes arrived, you already had problems in the Dodgers….

Yes, since much earlier. In the United States, sometimes you have to have two faces, and we Cubans are not known for that, we say what we think and that’s it. Regardless of whether I had made mistakes at some point, what really held back any chance of promotion in the Dodgers was that I had problems with the management of the team, and there, business is business. When they want to fuck you, they fuck you.

***

On the outskirts of the Victoria de Girón Stadium, Arruebarruena talks to a child, who says that Matanzas will be champion this year. “El Grillo” doesn’t stop smiling and supports him. Other guys from the Matanzas preselection surround him and try to discover the secrets behind the big leaguer.

The idolatry that awakens his figure makes Arruebarruena think that a reality hasn’t changed in Cuba: young people want to reach the best baseball in the world, the Major Leagues, and everything that comes from there is like a mirror to them.

“We always had that idea and it’s still the same. It’s normal, in life we seek to fulfill dreams,” points out “El Grillo,” who, like almost everyone, regretted the cancellation of the agreement with MLB that would allow Cubans to sign contracts in the United States without running so many risks.

“Now things have become difficult, and venturing to say that they are going to be resolved is creating false expectations. But it seems to me that both Cuba and the Major Leagues need that agreement; they will move as many pieces as they can move to revive it.”

***

Erisbel Arruebarruena saw from the bench of the Tokyo Dome how Andrelton Simmons sent Cuban baseball’s dreams flying in the Third World Classic. It was March 11 and on the island it was dawn.

“El Grillo,” who had been a starting player in the shortstop, watched the bulls from the barrier after being replaced by a newcomer (Yosvany Peraza) in the fifth inning. Although that was not his last game with the national team (four months later he was at the Rotterdam Interport Tournament), his adventure with Cuba really ended there.

Then came Haiti, the Dominican Republic, the scouts, the Dodgers, the 25-million-dollar contract, the American dream…. Throughout that period, uncertainty was the common denominator in the sports life of Arruebarruena, around which there was only one certainty: he would hardly wear the four-letter jacket again.

However, today that possibility exists, it’s real. “My first objective is to help Matanzas. We are preparing ourselves well and the goal is to win the championship. I’m going to play here as I played in Cienfuegos, and even harder, because it’s my comeback and I want to fight for a place in the national team, to help Cuba.”

Winning the championship sounds too ambitious….

Everyone here is focused on that goal. There is a good base, many here have been in playoffs. Ferrer knows the dynamics of professional baseball, he hasn’t worked in the United States, but he has worked in Mexico and other countries. That detail is going to be very positive for me, since I adapted to the professional dynamics, and it will also be very good for the team because of the things they can contribute from their experience.

Do you think it’s a motivation for the Matanzas players to play alongside a former member of Major League Baseball?

The motivation is mine, being here is a motivation. There are many expectations because Arruebarruena returned to Cuba and will play again. I want to meet those expectations, perform at 110% of my capacity, help everyone I can on the team and always convey positive thinking.

Do you regret anything?

No. I left because I wanted to prove myself in the best baseball in the world. I couldn’t establish myself, but today I’m a better player than before. Sometimes you think you know it all, but there’s a lot to learn. Now I don’t regret being here either. I’m a Cuban who returned to play ball and wants to give his best. I’ll so all it takes to return to the national team.