I’m going to run the risk of losing half of the readers since the first sentence of this article: Yulieski Gurriel (Sancti Spíritus, 1984) is the best Cuban baseball player of this century.

Don’t get me wrong, we’ve had stronger men (Alfredo Despaigne, Yordan Álvarez), more explosive (Yasiel Puig), with a better arm (Yoennis Céspedes), better fielders (“Candelita” Iglesias), better hitters (“Pito” Abreu) or better runners (Leonys Martín, Alexei Ramírez), but it’s difficult to look back and find another who has been able — for so long — to shine with the complete package: power, touch, speed, dexterity, versatility and defensive excellence.

Yulieski, a born baseball player, burst into full swing and soon became one of the main references in the domestic concert, where he played given his attributes and his performance, not because he was the son of Lourdes Gurriel. From a very young age, his talent opened the doors to the 2004 Athens Olympic team or the 2006 World Classic, which marked his definitive explosion as a star with that memorable home run against Panama.

For almost two decades, Yulieski’s name has been very recurring, especially because of his perseverance and work on the diamond. Among all the players on the island, no one has garnered so many accolades or headlines, although no one has also been so exposed to the target of criticism or been more in the media, which has cost him a great deal.

Yulieski, despite his enormous quality and stature as a player, for years he has had countless detractors. In his beginnings, some did not like his way of projecting himself, they reproached him for pretenses of greatness, despite the fact that he was always a silent, introverted and not at all pretentious player. Later, they pointed him from one shore due to his alleged relationship with the Castro family and Cuban power cupola, and from the other they called him a traitor when he left the delegation during the 2016 Caribbean Series after competing until the last out.

His move to Havana to play with the capital’s Industriales team after a life with the Gallos also put people’s back up, at a time when, in sports talk, many had already “hammered him” for his mental errors in the crucial game against the Netherlands in the Third World Classic of 2013, or for the double play in the finals of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, the most weight that a Cuban athlete has ever has to bear.

Bases full, one out, end of ninth inning, Cuba losing by one. That was the scenario that Yulieski found in that game, ultimately ending with a ground ball to shortstop that became the most remembered double kill in the history of national baseball. Since then, Yulieski’s head has been on the public guillotine.

“Many blame Yuli, but I tell them that he is not to blame. Double play is part of the game. The game was lost in the first inning when a short fly landed between three. That was the third out. The fourth bat came back and he hit a home run,” said Antonio Pacheco, manager of that team, in an interview.

As if all these individual evils were few, Yulieski has had to bear — and even pay — for the paternalistic discourse of a sector of the national sports press, which elevated him to a stardom position and, far from favoring him, only increased repulsion towards his figure in important groups of the national baseball fans.

Yulieski, however, has never given a public response out of place, as the extremely reserved guy that he is, he has known how to silently carry his demons, his faults…and also others’.

***

In MLB history — including the Negro Leagues — only seven players over the age of 37 have achieved the offensive crown, with the peculiarity that four of them are members of the Hall of Fame.

* Honus Wagner .334 (1911/Pittsburgh Pirates) -Cooperstown

* Tetelo Vargas .473 (1943/New York Cubans)

* Alex Radcliff .369 (1943/Chicago Americans)

* Ted Williams .388 (1957/Boston Red Sox)-Cooperstown

* Ted Williams .329 (1958/Boston Red Sox)

* George Brett .329 (1990/Kansas City Royals)-Cooperstown

* Tony Gwynn .372 (1997/San Diego Padres)-Cooperstown

* Barry Bonds .370 (2002/San Francisco Giants)

* Barry Bonds .362 (2004/San Francisco Giants)

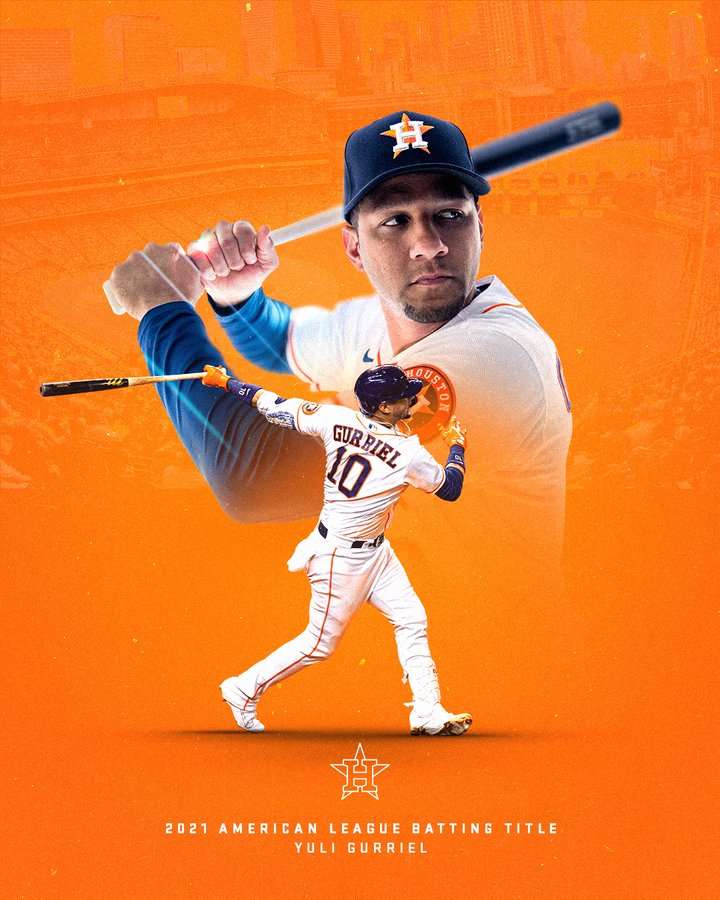

Yulieski Gurriel, 37, has joined that list, after taking the batting title (.319) of the American League in the 2021 season. The combination of longevity and performance is amazing in these cases, but in the Cuban another equally surprising detail is that he has achieved a historic award after making his debut in the Majors — as they say — three days ago.

This completely breaks the mold and puts us before a sui generis example. Without going too far, Wagner, Williams, Brett, Gwynn or Bonds began their careers in the Major Leagues before they were 24 years old and when they reached those “late” leadership in average they had a long service time. Yulieski, on the contrary, saw his premiere in August 2016, at the age of 32, and his first full season in MLB was at 33.

The other truly amazing thing about Gurriel’s title is that he has achieved it after a disastrous campaign in 2020, when he registered a .232 average, .274 on-base average (OBP) and .384 slugging, indicators well below his usual performance. Those numbers and an even worse performance last postseason (five hits in 44 at-bats and a .114 average) were enough fuel for many to see the end of his career.

However, Yulieski did not fall into the trap. He went home, took refuge in the family, and got his eyes on the 2021 campaign, just as he had promised his older brother in the fall of 2020, when the Astros were eliminated in the Championship Series vs. Tampa

“I’m going to prepare well, I’m going to put the return of the year in 21 and you are going to help me,” he told Yunieski, who has now shared the message after Yuli led the Astros in hits (169), offensive average (.319) and OBP (.383), in addition to being the fourth with the highest WAR (3.7).

Oddly enough, Cuba has not celebrated Yulieski’s batting title, and I’m not talking about official positions, in which the performance of the island’s players in the United States is not commonly credited. I am referring to a not inconsiderable group of fans who cannot stand him, and who are not even capable of bowing when he wins a major award.

A short time ago, when the Astros sign-stealing scandal broke out, they all turned their inquiring gazes on Yulieski. With somewhat ghoulish delight, they shouted from the rooftops that he had only won one World Series and had a 30-homer, 100-RBI season by cheating. However, now that there are no fraud lags, Yulieski continues to be subjected to a summary trial despite being the first Cuban with a batting title in the last 50 years.

***

Any sentiment contrary to Yulieski Gurriel has ended up turning into hatred. I no longer speak of offensive choirs in stadiums — the famous “Shakira” still rumble in the Latino stands —, but of offensive postures that one never thought to find in the sports arena, much less by Cubans to Cubans.

I cannot imagine a Venezuelan, a Puerto Rican, a Dominican or a Mexican denying or minimizing the achievements of any player from their land. It does not cross my mind that the Latin fans go to the extreme of saying that a certain player does not represent them. All this has happened with Yulieski, trapped in a network of hatred that is limited to lynching him and comparing him with Omar Linares, with “Pito” Abreu or with the Holy Trinity.

The words of recognition of those same stars who come face to face with Gurriel are worth nothing, nor the praise and signs of respect from his colleagues and specialists with a very high level of knowledge about baseball, both in Cuba and in in United States.

Yulieski lives in the eye of the storm, he has learned to hold out there no matter how murky the outlook becomes every time he pops his head out. Yulieski knows that he can perform at his best to the delight of his fans, but he also knows that the haters of the digital age will always be ready to tear him apart.

This has happened, for example, after his performance in the recent Division Series between Houston and Chicago White Sox, in which he had only three hits in 17 plate appearances. Logically, after the forced silence by his historic batting title, the army of detractors took advantage of the postseason slump and tore him to pieces.

Joe Morgan, Jim Thome, Iván “Pudge” Rodríguez or Eddie Murray, illustrious members of Cooperstown, went more than 20 turns without a hit in different playoffs and the world did not come tumbling down, a barrage of insults did not fall on them as well as expletives from their own partisans or countrymen, as if they were cruel villains.

With Yulieski it is different. His figure is exposed at the stake. It does not matter if one of his singles serves to tie a crucial duel, and much less does it matter that with his hits and RBIs he has placed himself at the top of the list of Cubans with the most hits and most RBIs in postseason history.

“He is the Cuban leader in that because he has played more than anyone in the playoffs,” some say, but under that maxim Yulieski should also be the island’s record holder in strikeouts or double play, and he is not. In fact, just to cite one significant example, Gurriel has nine fewer strikeouts than Cooperstown-inducted Tany Perez, despite racking up nearly 70 more appearances than the legendary Cincinnati Red Machine member of the 1970s.

Some prefer to ignore this statistical evidence, as well as keeping under the curtain that Yulieski is the Cuban with the most postseason appearances thanks to his quality and ability to remain as a title holder in a team that has played in the American League Championship Series in five consecutive seasons.

Likewise, it is preferable not to mention that of Yulieski’s 54 postseason hits, 14 have served to boost, seven have given the Astros a tie or lead, and 29 have arrived with a minimum margin on the scoreboard (18 with the game tied, seven with a one-run advantage and a quarter with a score disadvantage).

To all this we could add that, after 20 years playing mostly third and second base, Yulieski has mutated to become one of the best first basemen in the American League, a Gold Glove contender in more than one season. Simply achieving all of that after turning 32 and with no prior experience in U.S. professional baseball deserves, to say the least, respect.

Súper estrella ejemplo de sencillez