It was 2001. She was preparing to descend 74 meters in free immersion. She was 34 years old. She was wearing a wetsuit and a pair of flippers. It was all her gear, essential for returning to the surface with all possible propulsion after 2 minutes and a little more without oxygen. She inhaled a few times, holding on to the steel tower, and gave the signal to descend. She did not know how far she would go, but the goal was clear. That day, in Punta Francés, Isla de la Juventud, Cuba, Deborah Andollo (May 9, 1967) would go down to seek the possession of the record until then held by the French free diver Pierre Frola.

She had prepared for nine months with her mentor, Eduardo Medina, and during training it became clear that she could break the record without difficulty, but the sea is a temperamental environment, fertile ground for the unexpected.

We already know the end. Deborah dethroned Frola without setbacks, and as of that July 27 until today she has reigned without a consort in the depths of the ocean in the free body modality.

Twenty-three years later, no athlete, man or woman, has surpassed the Cuban’s record. Besides Frola, the only one to come close was the British-American Tanya Streeter, who in 2002, a year after the feat of the Havana native, managed to go down to 70 meters.

However, the history of the Cuban, four-time Central American champion, chosen among the 100 best Cuban athletes of the 20th century, with aquatic sports began three decades earlier, at the early age of 4. “Since then, sports became the center of my life,” confesses the record holder. “Since I was a child, the sea attracted me intensely. My father was an excellent swimmer. He was the one who inspired me to learn, but the one who took the initiative and took me to my first swimming school, the Ciudad Deportiva, was my mother,” she told OnCuba.

At 11, she began what would be her second discipline in aquatic sports, after swimming: synchronized swimming. She practiced it for 12 years, before falling in love with apnea. For 8 of them, she was part of the Cuban national team, with which she won bronze at the 1992 Pan American Games.

Like love at first sight, her love for apnea came unexpectedly. It was when she was modeling for a friend during an underwater photography contest in Trinidad that the seabed dazzled her.

Apnea is a sport in which lung capacity is the support of the athlete, in an environment ― the sea ― in which the hydrostatic pressure that the body receives is directly proportional to the depth traveled during the dive. Deborah Andollo would dedicate the rest of her sporting life to the discipline, started in 1949 by the Italian of Hungarian origin Raimondo Bucher.

She changed the nose clips and the leotard with rhinestones for neoprene, flippers, breathing exercises and the desire for her lungs to become as amphibious as possible. Two minutes underwater and the rest of the hours on land; that was her pact with the sea. She thus left synchronized swimming to literally immerse herself fully in the discipline that gave rise to the 16 world records she achieved until her retirement from active sports in 2002. Some of the most outstanding were: 110m without limits (1996, Isla de la Juventud), 90m variable ballast (1997, Sardinia, Italy), 115m without limits (2000, Parghelia, Italy).

With her crew in Parghelia, Italy (2000), when she achieved the record of 115m without limits. Photo: Courtesy of the interviewee.

Why did you decide to change discipline?

Synchronized swimming was the bridge to what would later become a sporting passion without limits. My time in this sport was one of extreme emotions, in which I discovered that, in addition to being a good swimmer, I was passionate and dedicated to what I did.

During the training sessions we did, I discovered that the anaerobic and dynamic apnea sessions were my favorites. Being underwater, without breathing, was pleasurable. I liked going down extra meters in the tests we did. It was thus, in the discovery of this new and unsuspected underwater ability, that the passion for synchronized swimming found a replacement. I said goodbye to that discipline during the 1992 Pan American Games, with a result that at that time was epic for Cuban synchronized swimming: a bronze medal in the team modality.

What is the training routine of a free diver like?

As with all other sports disciplines, the essence of apnea training is to create the capacity to tolerate physical effort, refine the technical elements that bring perfection to the sporting gesture, develop skills to adapt to the different loads you carry with you, and repeat until perfection.

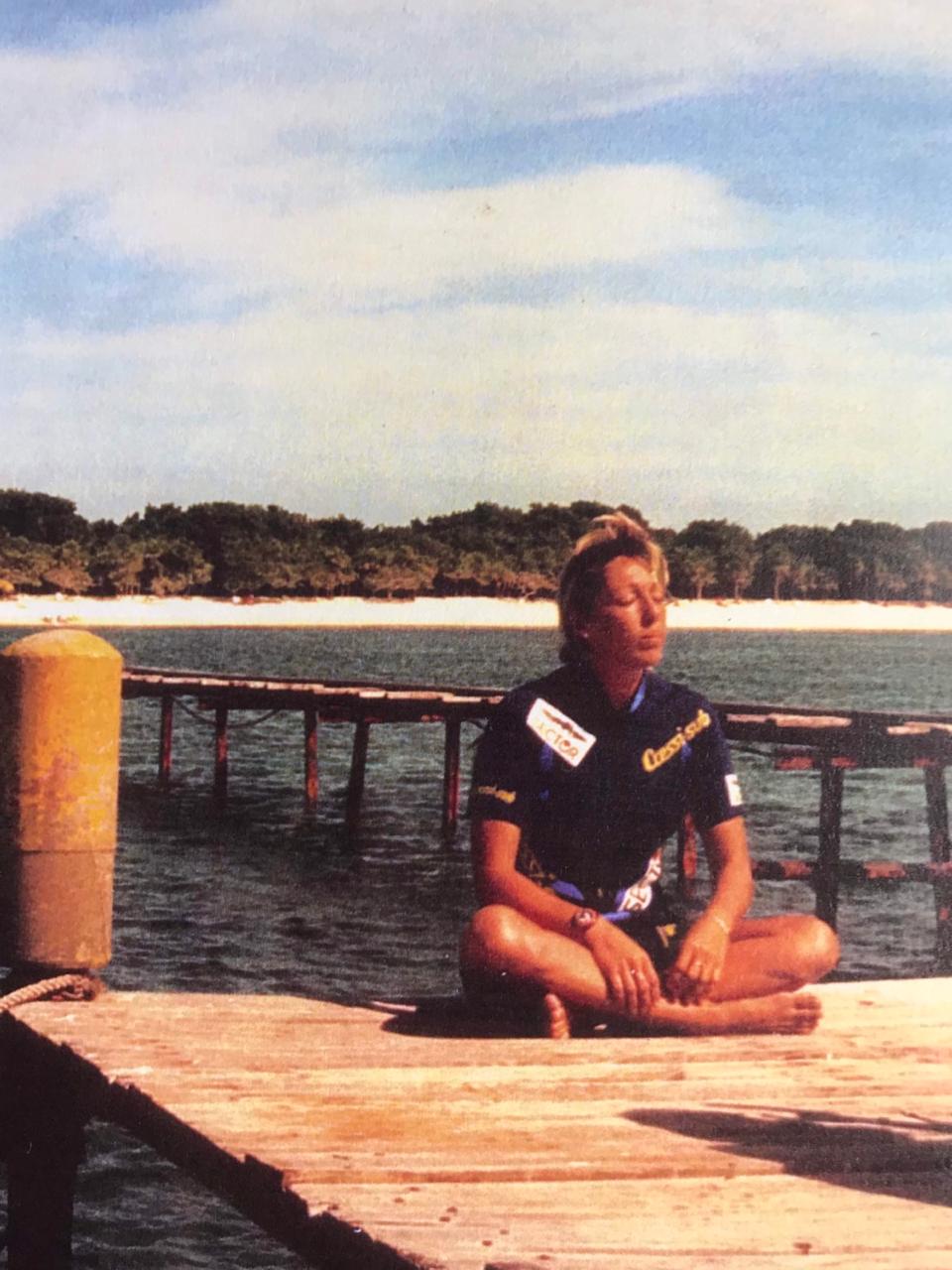

When you are in apnea, the body is subjected to enormous hydrostatic pressures. We would not be able to tolerate them without prior preparation. A strong and firm nervous system, bulletproof, is essential. Practicing yoga and pranayama (breathing exercises) helps to calm the mind, to have a better psychological and emotional disposition, to correctly oxygenate the cardiorespiratory system and, therefore, the bloodstream.

Understanding apnea implies understanding the processes of gaseous exchange, which is ultimately the essence of life. The brain and our body recognize certain levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood as safe. Training in apnea is precisely teaching and adapting the body to survive with little oxygen or, in other words, to tolerate its deficit, as well as to adapt to high levels of carbon dioxide.

The basis of these skills and abilities is aerobic capacity, the same that we achieve when we do training for running, swimming and cycling, for example. The rest of the preparation is more specific. It consists of performing cycles of repetitions of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the various modalities. Therefore, before practicing for real, you have to perfect these techniques through repetition and correction.

If you are in a good physical and mental state, you will be able to identify immediate improvements in training. As part of the “invisible training” you have to take into account other aspects that are very important: nutrition, supplements, clinical tests to identify organic responses to training loads, therapies and even recreation.

A free diver is above all an athlete in mentality. It takes a lot of concentration and equanimity to remain calm in an environment as unpredictable and uncontrolled as the underwater one. During your career in active sport, how did you prepare your mind for the moments of immersion?

A record is made in training. The best way to prepare yourself to achieve it is to train well, with perseverance and determination, avoid improvisation and, if you resort to it, do it in an exceptional way. Mental training helps to optimize thinking, making it useful and collaborative. The practice of pranayama, on the other hand, helps you to breathe well, to optimize lung capacity and increase it, to expand the rib cage and to make the intercostal spaces more flexible. The breathing exercises prior to a dive or apnea are very specific and complex, and involve a lot of preparation.

In 2001, at the age of 34, just one year before your retirement, you achieved the absolute world record for free immersion, which means that you did not carry any equipment with you; only your body. What did you feel at that moment?

It was a record achieved with great effort, especially because the athlete I had to beat, the French Pierre Frola, was one of the greats. It was achieved thanks to the dedication of my team of safety divers and the perfect preparation program designed by my coach, Eduardo Medina, current methodologist of the Manuel Fajardo Institute of Applied Sciences to Sport. I trained with great conviction and commitment and the record was achieved without setbacks. I felt enormous satisfaction, it was worth every moment of dedication and commitment.

In some way that was an extreme experience. What led you to set out to achieve that record and what did you feel when you achieved it?

The initial idea was to break my own record (65m), but during the preparation I got into very good physical shape and began to flirt with the male record, held by Pierre (73m). Within a few days, flirting became a reasonable possibility.

What is it like to be in deep apnea? How would you describe it to those of us who have never experienced it?

I went through a perfect progressive process to expose myself to that experience in the sea. First I was a swimmer, which allowed me to develop a close bond with water. Then, as a synchronized swimming athlete, I learned to enjoy being under water, to move within it in a controlled way. I am from Havana, so the sea was always present in my life. Enjoying it in all its forms was the best fun. With time and practice my body became more aquatic, therefore, any marine adventure, more than a challenge, was and is a passion.

Being in apnea is pleasant for the mind. You feel balanced. Silence is an opportunity to be attentive to the heartbeat, to let yourself be captivated by the presence of some marine species, and by the attractive mystery of exploring the unknown.

Deep apnea is a very introspective practice, I would say that it is like an immersion into the soul. It is the most daring and aquatic way that we humans have to explore all our potential.

The theory of our evolution states that, at some point in the past, we were marine mammals. Free divers and underwater fishermen are the representatives of this hypothesis. When we descend, we can preserve physical integrity to a certain point, thanks to some physiological adaptations, specifically vasoconstriction and bradycardia, which we develop with practice. This is a gift that we share with the marine mammals of our era: whales, dolphins, manatees, seals and sea lions.

Daughter of the sea, returning to the sea

“Since I was very young, I’ve belonged to the ocean, to its secrets and its myths. Among these myths, there is one in particular that unites the islanders in magic and in time,” she is heard saying in a voice-over in a video published on her YouTube channel, titled “Génesis.”

An open shot shows us a woman greeting Yemayá in the depths of the ocean. The current ruffles her hair, as if the coastal winds were also felt at the bottom of the sea, but her body remains on top of the stone, firm as the rock itself. Her arms move, in a sign of reverence, with a dynamism that becomes anachronistic within such a dense and saline environment. The woman wears a sapphire blue swimsuit, the same color that is represented in the Yoruba religion as the great mother whom she greets and honors every time she dives. It is Deborah, who moves from one place to another with the agility of someone who knows the environment perfectly, the nooks and crannies, the algae, the corals and the jellyfish.

“In those times, humans, made in the image and likeness of the gods, could descend to the depths like fish, and Yemayá understood that her work was going to be destroyed, that her children were not prepared for it. It hurt her to do so, but from that day on she deprived us of the gift of swimming like fish,” she says while recounting the myth of the genesis of the ocean, when a disconsolate deity whose name in Yoruba means “mother of fish,” retreated to the liquid depths of the planet to distance herself from the chaos that her children, the humans, had caused on Earth. Beneath her feet, oblivious to all the catastrophe on the surface, the goddess created her universe, and from there, legend has it, she allows us to enter and remain up to a certain space, only for a certain time. Transgressing her mandate costs us nothing less than our lives.

In the video, Deborah is not breathing, because the great mother did not want the gill slits that allow fish to inhabit their marine cosmos to be part of the human body, not even her own, that of such a devoted daughter. But the impressive capacity of her lungs after decades of training allows her to move with grace and ease in what is for most an uninhabitable territory, even if only for a few minutes. Yemayá lets her get closer, and, while she does so, the Cuban mermaid feels closer to herself.

Deborah officially retired from sports a few years ago, but neither sports nor the sea have stopped being part of her life. “I have two little dogs. On weekends we walk in the jungle and then we go to the sea,” she says about her routine on another island, Cozumel, where she lives with her family. In Mexico, she is an educator and instructor, in teams such as Los Tiburones, a group of triathletes who train in open waters. At Blue Yemayá Academy and the Mayan Sport Center, as an apnea and diving instructor, she teaches her students what she learned during her professional phase in Cuba.

On the other hand, environmentalism remains among her priorities, a task that she carried out formally during the five years that she presided over the Cuban Federation of Underwater Activities and that now, in Cozumel, she has found a way to explore, even within the most essential of contexts: her own home.

“Environmental education is part of daily life in my home. My children have grown up watching me diligently minimize garbage, recycle and take recycling to the containers designated for separation and selection. At home we separate organic from inorganic garbage, we make compost and create soil, we save water and electricity, we protect animals, those in the family and those abandoned, we avoid excessive and unnecessary consumption, and we work tirelessly to spread our practices to everyone,” she told OnCuba.

What do you like most about the ocean?

I am fascinated by its perfect composition of life, the harmony between its species. The unsuspected intelligence of some marine beings that are experts in mimicry, their symbiotic relationships and their self-fertilization. I love the diversity of the marine ecosystem and the anatomical perfection of some fish. Some are so perfect that they have not needed to modify their organic structure or physiognomy to adapt to the passage of time.

The ocean is also the greatest provider for the human species. I firmly hope that future generations will be able to repay its infinite kindness.

Your love and respect for the sea has been manifested not only in sports, but also through environmental activism. In 2023 you received the Isla Verde Award for your career in this field. After your retirement, have you found ways to continue being involved in these spheres?

The Isla de la Juventud was my home for more than 10 years. There I found the shelter and warmth necessary to build each record I achieved. Punta Francés is a historic place for Cuban and world diving. I couldn’t have had a better home. Because of all that, the fact that Pichy [Jorge Perugorría] considered me for the Isla Verde Award was very gratifying, and receiving it on the Isla de la Juventud was the best.

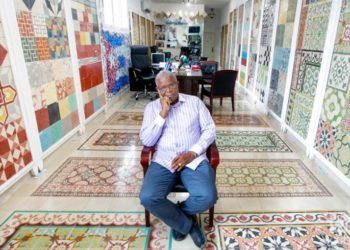

Sometimes, when I want to calm down or silence a harmful and useless thought, I close my eyes and navigate through that past, through the years of preparation at the Colony Hotel, the yoga session at 6 in the morning, breakfast, boarding at the Siguanea 40’ de Navegación marina, arriving at Punta Francés, searching for the dive site, reviewing the program, preparing the equipment, the rope, the descent cart, the divers preparing their equipment, the descents, the tension, then returning to training again: running the daily 7 km and again doing yoga. Some days everything was bright and perfect, others not so much, but all were special and unique.

Every person should have a place where they can shelter their sorrows, sadness and insecurities. Mine is that memory. I get there through my memories, which were frozen in time, they did not transform. I call that mental place “the Colony planted in my brain.”

For several years I had the opportunity to preside over the Cuban Federation of Underwater Activities (2006-2011). Through its scientific committee I was able to get involved in actions and campaigns aimed at environmental education and the protection of coastal marine ecosystems, and on occasion we collaborated with the Acualina programs and projects, together with Ángela Corvea, with whom we carried out beach clean-up campaigns and environmental education seminars.

In Cuba we need a true environmental revolution that awakens both the citizen conscience and the government’s will. There is a lot of work to be done, an example of what we lack are laws that minimize the environmental impact, that make it possible to care for our beaches and rivers and that encourage a sustainable interaction between citizens and the environment.

Environmental education on a larger scale, and the rescue of ecosystems, environmental areas and/or disasters have been somewhat relegated and even forgotten given the economic situation that our country is going through. The scenario is not very encouraging.

The dilemma extends to the rest of the planet, it is not just a problem in Cuba. As if so much loss were not enough, the world continues to bet on wars as an alternative to solve conflicts. The human and ecological losses that these imply constitute an enormous damage to the world. Cities and towns must be clean, more than just to look pretty. Garbage does not degrade on its own, it ends up in the ocean, polluting our seas and massacring marine species. Our garbage also pollutes rivers, the air, and heats the atmosphere; it pollutes water, our food source; it pollutes the land, where we grow our food; it kills mangroves and leaves marine species in infant and juvenile ages that take shelter there without shelter and food. Our garbage disconnects us from a world that was created with perfect precision.

What can we do locally and globally to preserve our oceans?

A lot. One of the iconic slogans of the Acualina project is “save your little piece.” We don’t have to wait for our beaches to be equipped with trash bins for us to be responsible with our waste. What we throw away is our responsibility, it doesn’t belong on our beaches, rivers, streets, parks or corners.

I understand that in Cuba there is a significant deficit in the logistics for garbage collection, especially in Havana, and this is something that obviously complicates the city’s hygiene system a lot and affects the daily life of Havana residents. But there are other resources that help minimize the volume of waste. One of them, which is within the reach of almost everyone, is making compost