For me, the best Cuban athlete in history… She has been the maximum expression of a figure within a group.

René Navarro. Cuban sports commentator and analyst.

Entering Mireya Luis’s home must provoke in a sports fan a sensation similar to the one she felt before going out to the tara flex to represent the Cuba team. Maybe anxiety. Her husband, Humberto Rodríguez, who was president of National Institute of Sports, Physical Education and Recreation (INDER), invites us into the spacious living room in the Fontanar neighborhood, in the Boyeros municipality of Havana. Everything is immaculate. The white floor shines. It is inevitable to feel a rare kind of tranquility. Harmony.

On the walls, in fine frames, are the photos that testify to an incomparable career. I look at them while Mireya still doesn’t show up. We stepped out into a side garden with a deep green lawn. Even. From behind a fence, a rottweiler, who apparently doesn’t like strangers very much, peeks out. We go back inside. It is one of the coldest days in January 2020.

“This is our hobby when we’re in Cuba,” Humberto says, leaning against a back door frame, while he points to the orchard in the backyard.

Cane, lettuce, tomato, papaya, mango, cabbage, tobacco… All perfectly distributed in a respectable plot of bright colors.

Humberto shows me the book published on Mireya’s life, written by the journalist Oscar Sánchez Serra. I had never held it in my hands before and now I hardly have a chance to leaf through it. Entre cielo y tierra. Mireya Luis, it reads on the cover.

“Look, there she is,” he says. “Take pictures of her cooking, nobody has that.”

At last, it’s her, dressed in a gray tracksuit with red trims from the Cuba team, and scarlet rubber gloves, with which she grabs the ladle to stir her dogs’ food. She smiles and waves as she whisks what’s in the pot. She has a 1950s pixie haircut, unlike the look she wore as a player.

After a few snapshots, to give time for the culinary work to finish, we go to the table. Near the stove. She crosses her arms and shrugs. It’s cold. On the wood, I put the camera, the diary, the recorder and, also, the book.

Mireya Luis Hernández was born on August 25, 1967, in the town of Aguilar, in Vertientes, Camagüey. It was a town of Haitian campesinos and that day the youngest of her mother’s nine children, Catalina, had arrived.

She speaks tenderly of her childhood. She remembers the sunrises in that remote landscape of Cuban geography:

“I would sit by my bedroom window and look at the dew a lot. I discovered a little light in a small ateje plant that was mine and I played with that. I was very very small, sometimes I didn’t like for 11 in the morning to come, because all that dew dried up.”

However, her mother’s tenacity and confidence in a better future for her offspring led them to the city of Camagüey, despite the fact that the father decided to stay in Vertientes.

“At first we had a dirt floor. We lived in a smaller, humble house, with less landscape; but it was also pretty. It had a river nearby and I loved that, although they never let me go. The other thing was the family activities, the dynamics of the house… You had to get up early, take a bath, dress well, eat what we had for breakfast without complaining, and each one goes to do the activity that corresponded to them. I remember that maternal discipline that seemed something like military service,” she says, unable to contain her laughter. My brothers, when they were older, would tell her: ‘Mom, we went through a cadet school with you.’

“Catalina was like that. I have great memories of her, of how she worked and struggled, how she was also elegant and how she took care of her hands, her skin; she being a campesina, a woman who worked the land, who cut cane, who gave birth so much and had to do so many things. In the closet, she had four or five dresses, nothing else, her French-cut shoes, the pants suits…”

When she left with her children from the small town of Aguilar, Catalina had Che Guevara in mind, whom she came across in the guerrilla advance before 1959.

“She had made many July 26th armbands without really knowing what it was. She joined because it was something that gave her hope; even without understanding it very well. She had people who told her: ‘Catalina, this is to be better in the future.’ And when Che passed by, she cooked for him, they killed a cow and she participated in all that. When they were leaving, Che met with the women and explained that they should get ready, that the Revolution was going to win and many opportunities would come for young people. That’s why she decided to go with all her children and leave my father. It was a risk, an act of courage from Catalina.”

In 1973, one of the events that would begin to change the life of Mireya, still a child, occurred indirectly. Her sister Mirta was on a scholarship in a place known as El Mangal, studying, and coach Enrique “Kiki” Larrazaleta went there looking for athletes for volleyball.

“He went, because before the technicians used to go out to hunt for talent and went where they had to go, and he captured two or three teenagers, among whom was Mirta. So, she moved to the EIDE in Camagüey and started taking balls to the house on weekends. She began to teach me to volley over the line and that’s how I learned to hit the ball from below, to receive, and I fell in love with the activity. I had never seen a game, not even with her playing.

“The next year they opened the new Cerro Pelado EIDE and recruiting was announced. I did the tests and it was a bit hard for me. There were many girls, and I was short, although I had long legs. They didn’t call me, and the list grew… Kiki and Cándida [Jiménez, Kiki’s trainer and wife] were doing those tests. I went and told him:

“Mam, I want to do it.”

“Darling, wait,” she told me with great affection and looked at me as if to say: ‘Oh, this dwarf, where am I going to put her?’ She says that she looked at me and thought: ‘Holy God, she is Mirta’s sister; but I can’t. Look how tiny she is!’ And then I saw the girls doing jumps and I did it and touched the ceiling, which none of them had been able to do.

“Mam, look, I touched the ceiling.

“I showed her the painted hand and she told me that they were dirty. So I stood in front of her and she told me to jump. I did it again, with both hands. She looked at me wide-eyed. She immediately told her husband: ‘Put this one first on the list.’ And he replied: ‘Candida, are you crazy?’

“That’s how I got my scholarship.”

She spent five years in the sports school. She stood out very quickly due to her skills and performance in competitions and, above all, she learned a lot from the coaches.

“They were exceptional. Cándida was a very young, elegant young woman. She was only 18 or 19 years old and she always encouraged us a lot, with a desire to work… I looked at her and thought she was huge, fine; but with a lot of character. On cold and airy days she put us under the hallway to warm up and we did exercises there. She would not take us out to the clay court.

“Now then, when we did go there, it was terrible,” she takes a sip of tea and continues. “The training sessions were, for our age, phenomenal. We spent almost three months just doing imitations without touching the balls. We were dying to play with the balls and they, imitations and imitations. I had a colleague from the Esmeralda municipality, Ana Lidia Martínez, who would say to me: ‘I’m getting bored because we don’t touch the ball.’ And the day we did it was perfect as if we had had a ball in the cradle. We had done so many imitations and technical exercises of each element of volleyball that we practically already knew how to play.

“They never did anything wrong. They always had a strategy, a form of preparation, everything in its time. They gave us many theoretical classes: we knew how big the square of the net was, the size of the terrain, the diagonals, everything. That was necessary because you have one more element that nourishes you, gives you wisdom when it comes to serving or spiking and, when moving on the field, you know the distance. We thought it was not essential and Kiki said: ‘This is very important.’ Little by little we learned. Then it went well, when we entered the court,” she recalls.

The adaptation to the life of the scholarship was not complex for Mireya. She confesses that she did not suffer if their pass was taken away (because Cándida also took away passes) and that they even stayed on weekends of their own free will to improve themselves and face the School Games in better shape. She only once fled to the guava field that was behind the center; the fear of jumping a ditch kept her from doing more.

“A well-painted school, those stairs, the blinds, all the same, the bunk beds… I remember that there were 40 bunk beds in each cubicle and a lady who slept there and took care of the girls, making sure that we all wore pajamas, brushed our teeth, and in the morning that we left the beds made up. The food was wonderful; they served ice cream, malt, milk, we ate chicken, pork ham, hot bread in the morning with an omelet. Uniformed cooks, always wearing white caps.

“The areas were taken care of. In the beginning, we didn’t have a small court, but we had the one with a clay floor, which they took care of keeping it neat, collecting the papers, and that the net was always well placed. Teachers had extra hours with those who had problems. If you didn’t pass the exams, you couldn’t go to the School Games. There were many conditions, and not only material but human. The teachers lived for this and we all enjoyed it.”

“Has that changed now?”

“Yes. Now the teachers go to school and at 5 pm everyone leaves. Before, it depended on how the activity turned out, what problem the athlete had and there was a commitment. I’m not saying that it is not so now; however, it is seen very little, it’s like doing it because you have to. Before, I think, people were a little more devoted, the love was stronger. We said that we were going to train over the weekend and the cooks were there, and the snack, your toiletry products…”

The path to reach the national team would not be easy. Every time a visit from methodologists from the Cuban Federation arrived at the EIDE, Mireya Luis fell into the group of possible cuts. Her height didn’t help her; but her physical strength and her will, along with the confidence of the teachers, had more to tell.

“I was never one of the prospects. I was not spoken to directly and I was aware of it. That didn’t interest me much, because my trainers were the first to tell me: ‘Don’t worry, you keep going. We are going to continue.’ They gave me exercises to grow, I always spiked harder, and I jumped with power. Which I liked. In addition, I did a specific job, they did not send me to do weights or strong physical work. I stood out in the competitions and I felt alive there.

“I shared it with my teammates and enjoyed the victories of the group; although the coaches knew that my sporting future was in danger. However, they saw that it could come. They believed in the work they did, they transmitted it to me daily and that kept me in high spirits.”

At just 13 years of age, she played a first-class championship, where she crossed paths with the champions Mercedes Pomares, Mamita Pérez, Imilsis Téllez, Ana María García, Ana Ibis Díaz and other stars of the first generation of the “Morenas del Caribe,” as they were called. Reaching that level was the goal that Kiki and Cándida set for her.

“I would say to her: ‘Mam, I see that they are very tall,’ and she would tell me not to worry. Until one day when she said to me: ‘Do you want me to tell you something? You are going to have the world at your feet with your jump.’ I never forgot that. It was a bit strong for a girl, I was missing about 15 centimeters to become a prospect. Until after five years of being in the EIDE, one day they decided to take me to the national team and try me out.

“We arrived at the national ESPA on the first of September. I started practicing there with the girls and about two weeks later they called me to Cerro Pelado. Every day a bus left for there. I started with the national team. There I continued the same: hitting the ball and jumping very hard and people said: ‘And where did she come from?’” She recalls her first steps as a member of the Morenas del Caribe.

Entering a court with those who were her idols in the sport was a shot of adrenaline for the teenager. She took notice of the best ones, she delighted herself and managed, in the process, to delight others.

“I was awestricken, looking at those women who did some exercises without dropping the ball, from here to there, and tremendous defenses; but when it was my turn I just tried to do it, and if it was necessary to attack hard, I would attack very hard and they liked it.

“Lucila Urgellés had an attack technique that seemed to reach heaven with her arm up there. I loved that Imilsis and Ana María passed me the ball and they liked it, because the ball they sent me ended in a spike; and they threw it up and I looked for it higher. I played with that. I was perhaps psychologically prepared to do everything I could. And it paid off and gave me confidence. Little by little they introduced me into the group. ‘Hey, where’s the ant?’ Imilsis would ask. They encouraged me and in a short time I began to be part of their group.”

In order to achieve that status within the team, she also needed to adapt to the strong physical demand of the training in Cerro Pelado’s training.

“I had never done that type of physical preparation in Camagüey, and I had my way of doing it naturally, without weights. Here when they said: ‘Let’s go to the track. Seven and a half laps in 15 minutes….’ I started running and arrived in the arms of Imilsis Téllez and Teresa Santa Cruz. I was so tired that I got there almost crawling. It was complicated. In the exercises with weights doing volleys and jumps they had to help me with the weights. For me it was something out of the ordinary. Kiki had come with me from Camagüey and told me: ‘You have to endure. If you put up with this, you stay.’”

At first, she would feel like fainting, until she got the hang of it.

The remembrance of her first days with Eugenio George makes her smile instantly: “He was silent, he just looked and laughed. I remember doing attack actions, bim-bam!, hard, and he did like this,” she reproduces a look from the corner of her eye, “he would turn and laugh. He never spoiled me.”

It was almost coming to settle. At the end of 1982 and the beginning of 1983, the girl from Vertientes represented Cuba in a winter tour of Federal Germany. Officially, she was already one more member of the Morenas del Caribe, a team with which she would dominate the world of volleyball in the 1980s and 1990s, giving continuity to the project that was cemented since the 1970s, especially from the regional and continental crowns, as well as the world scepter conquered in the Soviet Union in 1978.

Initially, she carried her number 3 on her back, which Ana Ibis Díaz had bequeathed to her; but something had changed, the coaches decided to turn her into a passer, since a setter with those levels of attack would be important for the team, although in the blink of an eye, it became clear that she was not made to serve balls.

“Ñico put me in that position. He told me: ‘You have good fingers, but you don’t have such a good volley.’ And it was true. Every time they put me to pass the ball, everyone went the other way and I was left alone waiting for someone to come and attack. Hey! Iron fingers. That was…and people laughed. However, Eugenio decided to send me on that trip as a passer.”

In the first games, she did not play much, until she was announced in a match. “Everyone: ‘Oops,’” she makes a dismissive gesture. “It was kind of terrible, and they took me out. And then, in the other set, I entered as an attacker, and I spiked a lot. I did very well.”

That day a passer was lost and perhaps the greatest spiker of all time was won.

With the 1983 Pan American Games in Caracas on the horizon, Cuba did not have a good feeling against the main rival it would have in the tournament. They had spent the year being defeated by the United States; keeping the continental scepter was a plan in doubt. Indeed, the title discussion in the Venezuelan capital was against the U.S. team, led by Flora Hyman and Rita Crockett. Mireya was given the confidence and the responsibility to enter to replace someone who had been one of the mainstays of the Cuban squad: Mercedes Mamita Pérez.

“Eugenio encouraged us to learn from them, from their tactical discipline and their movements. He put on for us videos of the U.S. team and we followed those guidelines. At the Pan American Games, we beat them in five sets. Difficult, but we did it. Imagine, for me, it was something nice, and Mamita was very happy. She told me: ‘I’m sad because the Americans neutralized me, but they couldn’t with you and that makes me happy.’ She carried me and hugged me. I think it was the takeoff, the moment I showed that I could really play in the regular field.”

In 1985 she won the Youth World Championship in Italy and came close to gold in the World Cup in Japan. In that tournament she had the opportunity to see one of the best volleyball players in history, the Chinese Lang Ping, who on that occasion did not manage to win the award for best attacker, since a Cuban volleyball player with the number 3 had earned said award.

“Lang Ping was the best player in the world at that time, the iron hammer of world volleyball. An imposing woman; everyone talked about her. I loved seeing her play with that ease and how she ran around the field and cheered on her team.

“When I come out as the best spiker, being on the podium with them, who were the stars, was a very positive feeling. She was at a fairly high level, spiking as she wanted. She had a little more experience and had improved her jumpability, physical condition and psychological aspect.”

“Did second place upset you?”

“No, because we already knew who we were going to face. I was quite sure that it was difficult.”

Unlike some of her teammates, she believes that the results of the 1980s were what they were meant to be. “Reaching the level is not easy. There are many aspects that must be polished to become an absolute champion, and it does not take three days. That is why my criteria with our volleyball: we are going to take time to raise the level because for this we need a team and a real head. To build that team in 1978, Eugenio had studied since the 1960s and had begun to build the Cuban Volleyball School with a little from here, another little from there. Nights and long weeks of elaboration, of watching videos, comparing, seeing; collectively and individually. Those things that now people dedicate sooooo little time to and say: ‘I’m ready.’ It isn’t true.

“Then, one thought: ‘We take them in the other.’ That ‘we take them in the other’ costs a lot! When you are the best, when you have to do something, you do it, and that is preparation. It’s my theory.”

The 1986 World Championship, in Czechoslovakia, saw China confirm itself as the greatest power in the world. The Morenas fought, but the level of the Asians and a Mireya at half-speed ended up taking its toll.

“In 1986 we lost; we still weren’t ready. I went to the World Cup nine days after giving birth. We got to the final, and apart from everything, they were better.”

“What crossed your mind when you got the news of the pregnancy?”

“It was so fast I didn’t have time to think too much… I didn’t realize it and I was walking like in the clouds. I had only one thought: the team. I had become an important player, not one hundred percent, because of course I never was, and that bothered me a little.”

“How did Eugenio take it?

“Very light. He was very intelligent. I imagine he thought: ‘Here there is nothing to do.’ Then we would finish training and he came over to my place to spend time with my daughter. He would carry her and say: ‘Wow! She has huge hands.’”

“Wasn’t it very daring to leave after practically giving birth?”

“Crazy, very crazy. Although I felt fine.”

“Was there any kind of pressure for you to attend?”

“No, quite the opposite. It came from me and my mother. She said: ‘Look, having a child is not a disease; being pregnant either. You must have certain cares. I stay with the baby. You go and carry out your commitment with your volleyball.’”

“How did the doctors react?”

“That was a big dispute, I remember that our doctor Reynaldo Betancourt entered into discussions with the director of Sports Medicine. I went to the airport and suddenly the director was there talking to Eugenio; I also saw Chela, who was the technical director, and there were several doctors. I finally boarded, Betancourt sat next to me and nothing happened.

“First we flew to Germany because we had a base there before and I stayed for about ten days. I started to go down to the court. The next time I was dressed for training, then I went into the field and collected balls, until one day I started to volley. I had no strength at all, I couldn’t lift a kilogram of weights with my legs, I was very skinny, but I was fine, and Betancourt was always by my side.”

In the event under the five rings of Los Angeles 1984, Cuba and 12 other nations did not participate in support of the boycott called by the Soviet Union. The position was in response to a similar one adopted by the United States and 64 other countries that did not attend the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

“In 1984 the group was ready. I think that perhaps we did not reach the gold there; however, we were going to fight for it. We were all very excited. When we found out that it wouldn’t be possible, I don’t remember saying anything, I didn’t know what the Olympic Games were, what we were up against, and one day Josefina Capote explained to me and I said: ‘Fina, then are we going to miss that?’ However, it was a decision of the Revolution, of Cuba. Everything happened, we found out the results and we continued.

“We won some competitions, in others we came in second, and Eugenio did his work, the eliminations, and 1988 arrived. We were in really good spirits then. We went to Japan, where the twelve best teams in the world were. We beat them all and in the blink of an eye, they told us that Cuba would not be in the Seoul 1988 edition either. We cried, for some players it was the last hope of participating in the Olympic Games and they said: ‘I left without the final goal.’ It was quite sad,” recalls Mireya, who was marked by missing out on the experiences of two consecutive summer events.

All of a sudden, Mireya stands up and goes quickly to the kitchen, while she continues talking about volleyball, until she leaves the subject.

“Today my puppies eat deliciously because I make their food as if it were for me,” she says as the crackle of the fire against the pot grows louder. “They are raised with a lot of love.”

She finishes stirring with the ladle and taps the edge of the pan to shake it. But she continues on the subject of the animals, and she remembers Lala, the mother of the rottweiler that Humberto showed me an hour before.

“She jumped more than me. She caught the pigeons that flew low. The people in the neighborhood called her Mireya Luis. When you were leaving… You brought a backpack, right?” she asks and continues when I nod. “Well, you took the backpack and she stood at the door, and to let you out you had to do it without the bag. Natural instincts. That was Lala…”

Cuba’s absence in the Seoul Games put the Morenas del Caribe on an unusual journey. They would play volleyball for the people, people who needed it very much; although this would not prevent a certain uneasiness in the face of the revelation of the destination that awaited them 11,500 kilometers from Havana.

“We received a call for a mission from Fidel: go to Angola to see the soldiers. We arrived very scared. We landed at an airport, where everyone was Cuban; we found volleyball people there and moved to a place that looked like a school. We were quite afraid at night; we did not want to bathe or drink water. The Cuban troops supplied us with everything.

“An Angolan named Alfaro cooked for us; Regla Bell named him Alfarito. He made chicken and said: ‘Today we are going to eat chicken.’ The chicken was the size of a cube and we: ‘Alfarito, serve me more.’ And he would reply: ‘I don’t have anymore.’ Once we heard children behind the kitchen and I think Regla herself or Magaly [Carvajal] discovered that he had about eight children, all of them small. And we realized why he was cutting the meat into such small pieces. We felt so sad that we didn’t want to eat. Eugenio had to force us.

“One day we met part of the Cuban army, we saw our colleagues from EIDE. It was sad. They sang on top of the trucks and had fun watching us play volleyball. We spent our time there like this: trying to make those people who were risking their lives a little bit happy.”

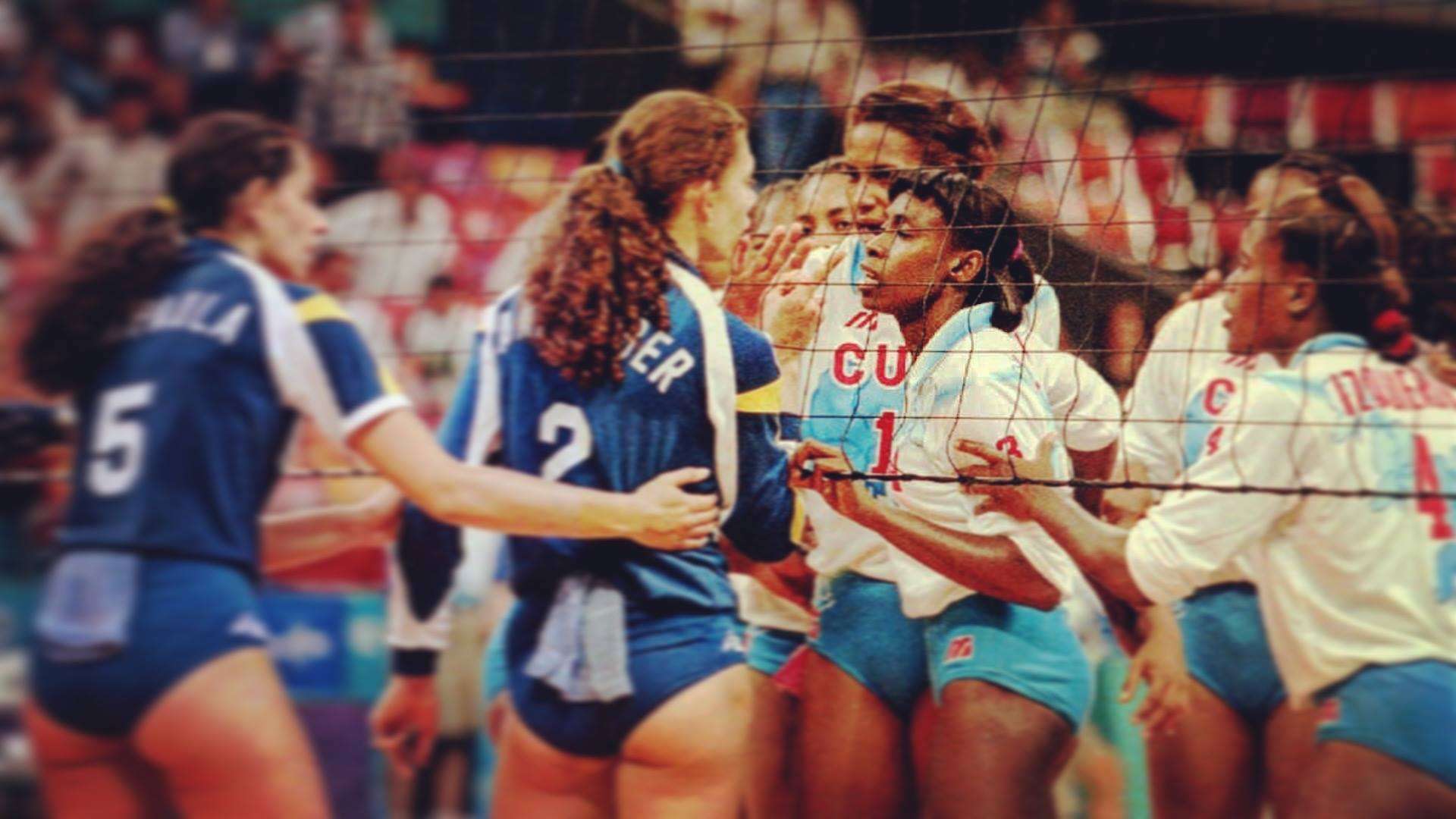

At that time there was a certain rivalry with the Peruvian squad, although Mireya admits that it was never the same as with Brazil: “There were their little things. The Peruvians played very good volleyball; they had a tradition and a great team. Because of their way of speaking, sometimes it seemed to us that they were offending us or laughing at us, and we lashed out with spikes and with words too. But it wasn’t that much. We were good friends, and we were always together; however, in the competition, we played hard.”

“In an interview, the player Natalia Málaga declared that they had to choose well the moment when they insulted the Cubans because it could go against them. Did the fact that the game ‘heated up’ favor you?”

“That’s how it is. They were very careful about it. Once the passer yelled something and Natalia told her: ‘Hey, don’t do that, because they get mad.’ Then we started to spike hard and she said: ‘Fuck, bitch!’”

In 1989, a challenge awaited the Morenas del Caribe and also Mireya. The first place in the World Cup was something that the Cubans had not been able to achieve and the player from Camagüey was eager to conquer it; it still had the flavor of second place from four years ago.

“It was my second Cup and I already wanted to win it. We did the last part of the preparation in Mexico, for the first time we went to the height. The training there was strong and very satisfying. We did it with great enthusiasm. The team was completely renewed with Magaly, Lily [Izquierdo], Regla Bell. A national team of young athletes with a lot of responsibility and level. It turned out really wonderful.”

With seven wins without losses and just one set conceded against the Chinese, Eugenio George’s girls took the tournament title and Mireya was chosen as the best spiker and the most valuable of the event. It was a different sensation, despite the fact that she had been awarded in the previous edition.

“I didn’t like going to receive an individual award if I didn’t win. For me the team result was always the first and most important thing. Later, if you stood out, it was a personal satisfaction. Being able to collect those individual awards after having received the team award was the perfect complement, because we didn’t always win. In 1985 I could not savor it, because the objective was not achieved one hundred percent. That’s why 1989 was special. It was my team, and it was me.”

Since the 1971 Pan American Games in Cali, Colombia, Cuba had not relinquished the crown of continental games in women’s volleyball. In 1991 the fight would be in Havana and, apart from the commitment to stay at the top of the Americas, achieving victory would be even more important: Cubans were beginning to face one of the most complex economic crises in their history.

“I had surgery on my arm at the beginning of the year. For the first time in twelve years, we spent that time in the country. I got on a motorcycle with a cousin of mine, and we slipped. We didn’t fall on route, but when we went to get on. That caused a dislocation in my shoulder and Dr. Álvarez Cambra said that I had to undergo an operation. I had recovered for the Pan American Games.

“Politically, the country was entering a complicated period and the will was immense. Fidel did I don’t know if magic, all those things that he used to do when nobody expected it. We held tremendous Pan American Games. The Special Period began, people with nothing and only the satisfaction of being able to enjoy sport, because for Cubans it is visceral.

“Now I suffer a lot. I remember that we were ashamed when we lost because we hadn’t complied with our family and people, and also with ourselves, because we made a great effort and said: ‘We can’t afford to get there and lose.’ And I think the people fed off of that at some point. It was what they took with them: perhaps an empty, dissatisfied stomach; but a soul full of hope to say, ‘we are the best, the athletes are there, we trust them.’ Those were some of the sure things they had at the time.”

Sometime later, in Catalan lands, on Friday, August 7, 1992, the dream of the Cuban Volleyball School came true. The Spectacular Morenas del Caribe touched Olympic glory by neutralizing the Unified Team, made up entirely of Russian players as part of a delegation that had exponents from twelve of the fifteen former Soviet republics, three sets to one in the final.

“It was wonderful. We knew we had the chance and we could win. My team and Eugenio were in charge of making it felt. All of this was planned. Eugenio knew how to adapt to that Special Period, to plan and carry out dynamics that would maintain the discipline, desire and hope of getting there. He studied everything. We did the last stage of preparation in a small town called Zocca, in Modena, Italy. It was located on top of a mountain. If there were forty houses it was a lot. There was a court and a gym. There we were. From there to Barcelona, with the idea in mind that we were going to win.”

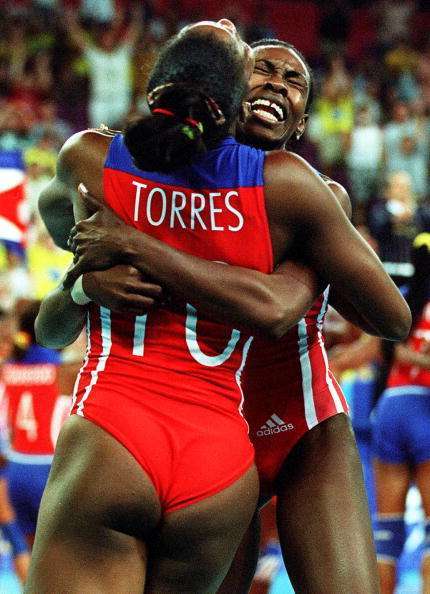

The last point obtained by the Cubans that night at the Palau Sant Jordi in Barcelona did not mean anything other than devotion. In a hug, in the image of complicity and respect, two of the fundamental components of that victory merged: Mireya and Eugenio: “It was his dream, to lead Cuba to be an Olympic champion, and he achieved it. All the work was summed up in that day. Many things were expressed in that hug and that look. I congratulated him, because he had been the architect of that work and it was the greatest thing for him.”

The following year, Mireya Luis added the 1993 Grand Prix to her list of successes, and when asked what happened to Cuba in these events that were not won frequently, she answered with a laugh that the conclusion she and Lily Izquierdo reached is that the team did not know how to play for money.

On the subject of payments, often controversial, she explains that there was a scale. “The performance was not even. There were bench players, they had a level, but they were always a replacement, and they knew what they were up to, because Eugenio said so and I was in charge of leading the group dynamics and that people knew who the most important athletes were. That is, we all were; however, it was clear who were those who carried the team’s weight. If there were mistakes, it will have been later; at that time everyone knew their place, to avoid jealousy and differences. In the case of individual prizes, 50% was handed over and you kept the other half. We managed to do that. And there was no discussion.”

From the undefeated triumph in the 1994 World Cup in Brazil, Mireya recalls that the team was in a “super stellar” moment, although leaving the box of sets against zero was simply a product of preparation. She also confesses that reaching the final with the possibility of materializing such a feat did not worry them, but rather the desire to do so stimulated them.

“We used to say: ‘If we win quickly, we’re going to rest.’ And we were a machine that was in incredible shape. We didn’t think it would be the same in the final against Brazil; however, it was.

“They were already believing that they could. They did religious ceremonies on television and said that Yemaya had been shot in the jungle and we: ‘Oh yes? Alright. They don’t know what our Yemayá eats.’ We laughed about it, and we had a lot of faith and strength. We commented: ‘They could have shot an elephant, but against us they won’t be able.’”

In that final confrontation, the Brazilian public wanted to play its role. Therefore, the Morenas’ first objectives were to dismantle the enthusiasm and erase from the equation the weapon that being the locals meant for them.

“There was silence. They threw thing at us and said all kinds of things, and we concentrated on the game. Before, in the dressing room, we talked. I asked Eugenio: ‘What do we have to do?’ and he answered: ‘Make the public shut up. You have to silence the public and you know how.’

“Magaly said: ‘I’m going to make the first 10 points,’ of those she made several with the block: ‘I’m the best,’ she says between laughs, ‘the best of the best.’ Reglita [Torres] was young and had a great level and a lot of energy. I told her: ‘Regli, save your strength,’ and when we greeted each other they squeezed me tight. I didn’t want them to wear out, because the Brazilians were trained and I was worried that there could be a five-set clash; but no way, what was on our side was very strong. We silenced the public and it was wonderful. That’s where Bernardinho’s frustration began. We finished him off.”

The rivalry with Brazil would see its chapter of greatest impact in the 1996 Olympic Games, in Atlanta, United States. The famous altercation of the semifinal between Cubans and Brazilians is almost remembered more than the second consecutive gold medal of the Morenas del Caribe, who did not start the tournament on the right foot.

“I think the team arrived a little psychologically tired from so much success. You can’t get used to it because you fall into monotony. In the villa, there was a hairdresser’s, and we were there, saying that we were going to win and we were not worried. Eugenio was worried. We lost to Russia, to Brazil, and it was our turn to play the semifinals against the United States. He brought us together that day and talked about many topics. He started with wonderful stories about Cuban women, about Cuba and suddenly he used a dirty word and people reacted. Then he said: ‘That’s Cuba’s reaction,’ and that’s how it was, we took the Americans and swept 3-0. We passed and it was against Brazil: things got nasty then!

“It was hard. In the dressing room, after the technical meeting, the girls told me: ‘Mireya, and so? How is this going to be?’ And I answered them: ‘We are going to offend them!’ Apart from the tactical, we began to say things over the net and that distracted them a lot. The referee at some point called my attention, because nothing could be said and I turned to the group and told them: ‘Girls, keep saying things to them!’ That’s how we did it, because they were very good, ready to defeat us, but they lacked the detail,” she smiles shrewdly, “of not having prepared enough from a psychological point of view. To win you have to take in everything.”

With the last point, once again achieved by Mireya Luis, came a shout and struggles followed one another under the net. Later, the heat turned into fire in the dressing rooms: “Márcia [Fu] was a tremendous blocker and I had to use my skills 100 percent. Already in that last set, I had ripened her. In the dressing rooms, there was a fight and I separated them because we were going to the final, nothing else mattered. We won. I told those on the bank, Ana Ibis [Fernández] and Idalmis Gato: ‘You fight, the regulars can’t fight,’ but Reglita and Magaly were really upset… In the end, everything calmed down and we went to our dressing room. We were there until the late morning hours.”

For different reasons, after Atlanta, Mireya distanced herself from volleyball a bit. She felt tired and the separation of Eugenio George due to differences with sports executives, fifteen days after having achieved the second Olympic gold and announced in the Granma newspaper, demotivated her a lot.

“I spent about three months without training and the news came that they had removed Eugenio. A very unpleasant moment. They never came to give us an explanation about it. No one came up to talk about the fact; things were attributed, comments. A note appeared in the newspaper with arguments that nobody understood. They were moments of uncertainty because from having Eugenio to not having him the next day… He made us. After this situation, he went home, put three or four balls in the trunk of his old Lada and went out to the parks with a net to teach the children to play. That’s what he did. He didn’t go anywhere, nor did he comment. Nothing.

“The people who caused that at some point must have felt ashamed. A sport that had the best performance in this country. A team of women completely directed by that person in all aspects, because our attitudes, preparation, results depended on him… everything, and no one thought of that. It was decided and that’s it. Very badly. I took it as an act of jealousy, something disrespectful of our effort and dedication.

“I was interested in being as close as possible and when Humberto Rodríguez entered INDER and wanted to look for him, he asked me and I said: ‘I don’t think he will return; however, what you are going to do seems perfect to me, because we’ll never have someone like him,’ and he finally managed to bring him,” she says.

Mireya Luis had added to her successes in that decade the World Cups of 1991 and 1995, taking the laurels as the best attacker in both editions, in addition to the recognition of the most valuable player in 1995. In 1998, she would revalidate the 1994 title in the World Championship and, although at that time her role in the group was changing, she affirms that she took it in the best way.

“I had a very strong psychological exhaustion. I didn’t want to give up volleyball, but it was like wanting a vacation for a long time, and in high performance, you can’t. I needed to be calm, to do other things, and that is difficult. Eugenio and Ñico understood it and Yumilka [Ruiz] was there and I was worried about her good performance. She came with characteristics that were more or less similar to mine, a school like the one I had, the same technicians, perfect for the moment and she gained the confidence of the girls and gradually took over.”

The fact that she describes the Sydney 2000 Olympic event (the competition in which she had the least weight in the court) as the best passage of her career, speaks of the personality of this woman, a mixture of Haitian and Cuban blood. It is the thought of the eternal captains.

“It was the consecration of a group. I never felt like an individual Mireya, I was part of a group and I had a responsibility. Sydney was the moment that brought this group to glory, where we were able to express the existence of a result thanks to all the work, achieving something that no one has been able to materialize in the world so far: a team of black women from a blocked, tiny country, winner of three consecutive Olympic Games.”

“How did you experience the final game from the bench?”

“Wonderfully. I felt like a player, almost a coach. There are chances that I told Eugenio or Calderón to let me speak. I had the honor, the satisfaction, the luck of being there, of experiencing it, and looking each of the teammates in the eye in the court and feeling what was going to happen. From seeing Reglita, Ana Ibis, Regla Bell, Marlen Costa, who was extra class that day… I knew victory was on the way.”

However, her path was not always made of wins. Compared to so many moments of euphoria, she recounts that one of the most difficult moments in her career came after her first knee operation, in 1990: “That was the saddest thing. I thought I couldn’t jump anymore. I was in the hospital finishing the last weeks of recovery, I went to the court and said: ‘I don’t know if I can or not.’ Only my mother and her words got me out of that ugly period.”

From Eugenio George, she always received a smile, a friendly hand, that of a father who at first, in the days of Camagüey, doubted, but who later, like the genius that he was, did not have the slightest qualms about admitting his mistake.

“He left me with an immense feeling of nobility. The greatest people can be seen in their details, that’s where his greatness is. He was so big that he was embarrassed to ask you for a glass of water. A man with a lot of wisdom and, at the same time, with extreme humility. That is what remained in me: that tremendous figure of incalculable modesty and simplicity.”

“How do you remember the day of his death, in 2014?”

“It was very difficult. We knew that he was ill; we could expect it at any time. However, what hurt me the most was the lack of recognition, which he deserved. Fidel found out from me. I told him through his son.”

“Do you think he’s been forgotten?”

“Of course. Too unfair. The volleyball school is Eugenio George. If they give it another name.… Cuban volleyball is Eugenio George and that is ignored. Not having the capacity to understand what is great, what is good. We have lost opportunities and we have been very inopportune because we have many things in our hands and Eugenio George is just one, the result of the Morenas del Caribe is just one. It is still missing and will be missing. So we want to continue blindfolding people, even though the smart ones know what the sport was, how it was run, who did it, and why they were successful. Now we are ignoring so many things…”

“Can we continue talking about a Cuban School of volleyball as a philosophy?”

“No, no. It doesn’t exist.”

On March 3, 2001, Mireya Luis said goodbye to high performance volleyball in a packed Coliseum in Havana’s Ciudad Deportiva, putting the perfect touch to the end of one of the most impressive stories in the world of sports. Next to her was her mother, Catalina. In the boxes, Fidel Castro was waiting for her. Today she appears in specialized media listings among the ten best female athletes of all time and her influence goes beyond sports.

The controversy unleashed with the delivery of the award for the best volleyball player of the 20th century to her partner Regla Torres does not take away her sleep. In short, she always played for the team.

“The International Volleyball Federation (FIVB) decided to do it that way and she was Reglita. We weren’t the best of the century either, because they wanted to put on an act and it went wrong because in reality, the best team of the century was ours and not Japan.”

“Did that award generate any harshness with Regla Torres?”

“My affection for her has always been the same, it has never varied. There were many comments, people who hurt her, comparing. That was wrong. At all times I tried to make her never believe that I had felt bad or anything like that. I actually have not felt bad, I have expressed it everywhere, and I adore her.”

“Do you think there was an intention to give the impression of a confrontation between the two of you?”

“Yes. It hurt her a lot, until she reacted. She knows that in my heart there is only affection for her. Also, neither she nor I played to be the best of the century; we did it simply to win. It was a decision in which neither of us had anything to do.”

To Mireya’s merit sheet we can add that she is one of the four Cubans who, along with Eugenio George, are in the Holyoke, Massachusetts Volleyball Hall of Fame, the place where the beginnings of this sport in 1895 are recorded. Mireya has never gone there; however, she wears her ring with much honor.

“What does it mean to represent Cuba as an official of NORCECA and vice president of the FIVB?”

“It’s something similar to when you play.”

“Which is more difficult: playing or leading?”

“Leading. And more at those levels, where you have to be very diplomatic. Sometimes laws, rules are at stake and, sometimes, your country does not classify, and you feel bad; but you must speak as a representative of the FIVB and not as a Cuban. It’s complicated, but important. Athletes have to be prepared. They are the true ambassadors of the sport; they are not the leaders who have been in I don’t know where for ten years. I organize events and, in the countries around there, athletes are the ones who look for sponsors, big companies and involve the authorities.”

“What’s missing for Cuban volleyball to resurface?”

“Trainers have to be made. The players are there. Technicians to teach women to play volleyball and convey that we are winners. That they really have a plan. Decisions cannot be made by the commissioner or the president of the Federation; the director is the one who leads the whole process.”

Eugenio George, says Mireya, said that the Olympic medal was built every day in training. “Those records are the ones that are scarce. Each aspect has to be studied a little deeper. That is what Eugenio did, and it is what the new technicians have not learned or have not wanted to learn. I have not seen an Olympic gold medalist who has spent ten years in a national team and has no subsequent injuries or aftereffects of high performance. In the world, and I know almost all of them.

“The concepts are left afloat here and we go back every day. We are no longer Central American champions. The analysis is purely sporty, we make it very difficult and we talk about a hundred variants that have nothing to do with it. It is true, the world is full of resources; but we had much less than we have now. I drank water with sugar as a recuperative; I didn’t have Gatorade or anything like that. ‘These are other times.’ Well, if we are going to think like this, it is another sport, we are going to zero and lose and continue losing.”

Apart from those who taught her along the way, Mireya has words of gratitude for the former president of INDER, Conrado Martínez, and the former volleyball commissioner, Inocencio Yoyo Cuesta. “Conrado was one of those leaders who went to the field and touched things with their hands. That is what sometimes the athlete needs: true closeness and not the ‘blah blah blah.’

“And Cuesta was a spectacular representative, very close to us, with details on birthdays.… Sometimes we played hookie, because they gave us two days to go to Camagüey, and we spent seven. You took them, because it was not easy and Eugenio sent us to the commission: ‘Get out of here. Go. The commissioner is waiting for you.’ I remember that I once told him: ‘Yoyo….’ and he: ‘Let’s see, what are you going to say? If I know that you are tired from training and you needed to take those days. But what am I going to tell Eugenio?’ He wasn’t conspiring with us; although he understood us very well. The thing is that it was a collective of luminaries.”

“In a word, how would you define your life?”

“Oh! Imagine, I can’t be very pretentious,” she smiles and thinks. “Fortunate,” she says like lightning and bursts out laughing.

Mireya Luis says that she is half campesina. And it is that she is very Cuban. She is a dancer guarded by rum and tobacco, and to the rhythm of her Van Van and Gente de Zona. Speaking of cigars and the countryside, we went out to the part of the house that is one of her treasures.

It’s already past 2 in the afternoon and the red earth plot of land is still wet almost everywhere. My shoes know it from the first moment. Mireya shows me all the crops and walks to the back of the furrows, while I take many photos of her. Click, click.… The camera shutter is heard while Mireya proudly poses next to the production specimens: cane, tomatoes, papaya.

“I distribute lettuce to the entire neighborhood,” she says, walking through all the greenery.

She looks happy. Perhaps she is reminded of that ateje plant that excited her as a child with the little light. Behind you can see a booth where they sew tobacco. The cold of January does not subside, not even with the sun in its punishing schedule. My shoes, plastered by the earth, lost their white and blue. The return to the immaculate floor of the interior of the house will be difficult.

“And now? I think it’s better to take them off and put them on when I leave.”

“No,” says Mireya, and she pulls out an old mop that she folds on the floor. “Clean them here.”

The first attempts are in vain. However, most of it eventually falls on the mop and, carefully checking that I wouldn’t make a mess, we went back inside.

As I ask for an autograph for a colleague’s mom, I start clearing the table. I put away the camera and the notebook.

“Ah! You have the book?” she asks when she sees her biography on the table.

“No. Humberto brought it when I arrived. I don’t know if it was for me or if he was just showing it to me.”

“Take it,” she says.

“Thanks, but then you sign this one for me….”

“To J. Luis with love and respect. Successes!

Mireya Luis

#3

Cuba

1/22/20.”

*This interview is part of the book Tie Break with the Morenas del Caribe, which will be published by UnosOtrosEdiciones.