Cuba is not only known in the world for its cigars and rum, but also for being the homeland of the Havanese, a charismatic companion dog that was born on the island two centuries ago. It is a furry, vivacious, cheerful and affectionate little lapdog that has always been very popular in Cuban homes. And, although until the 1990s it was almost unknown, today it can be found, reaping success, on beauty tracks on all continents.

In the United States, where it is seen a lot on the streets, it occupies number 25 — out of a total of 1999 — in the list of the most popular canine breeds, according to the latest ranking published by the American Kennel Club — the canine association that governs there everything related to purebred dogs.

But, before this explosion of popularity and, like everything that is not well known, the Havanese gave rise to numerous legends, myths and rumors that are still repeated. Some say that Italian navy captains brought it to Cuba to give it as gifts to Cuban women of ancestry; others say that it came to the island from Argentina and Peru; others — the most daring — say that it came like that, “ready and packaged,” from the western Mediterranean, and there are even those who affirm that the legendary Catalina Laza — a noble and beautiful Havana lady who the only thing she did, apart from scandalizing the society of her time with her divorce, was to lend her name to baptize a flower — raised them.

Very nice, very exotic and very romantic. But none of that is true. In fact, in Cuba things were different: the Havanese, as luxury objects that they were (today they are still dogs that are sold at high prices), were reserved as special gifts for distinguished guests and highly appreciated people, because, in addition to the fact that giving fine dogs is a sign of respect and deference, it is an ancient custom. Cubans have always been characterized by being splendid and obsequious with their friends and guests.

The truth is that the ancestors of the Havanese, a canine breed recognized by the International Canine Federation (FCI) as Cuban, arrived directly from Europe in the mid-18th century, although not from Italy, but from Spain and France, perhaps commissioned by some noble Cubans lovers of lapdogs or eager to follow European fashions (something that was done with great interest in Cuba), or perhaps even as a gift from their husbands and relatives to serve as entertainment and company during their long leisure hours at home.

And so it turned out that, over time, the little lapdogs (bichoncillos) that arrived in Cuba — a type of small, long-haired dog is called a “bichón” — began to become Cuban, until they ended up becoming “something else,” a new type of lapdog, a Cuban lapdog, that was then called a whity from Havana — how the name of the capital of Cuba was spelled in Spanish until 1820 —, Havana silk dog or Cuban white.

It was a funny little miniature dog with long, silky white hair that aroused a true passion in Havana society, to the point that some incisive chroniclers of the time came to criticize women who entrusted the care of their children to domestic servants while they spent long hours combing and bathing their little dogs.

The Havana whity didn’t weigh more than 5 pounds, and its hair was so long that, when walking, its feet couldn’t be seen, so it seemed that he was sliding on the ground. And, although that was very funny, to better keep the animal clean, some owners chose to trim the hair on the lower part of its legs and on its face, which is why it is often seen this way represented in the pictures of those times. Although it was known in Europe, the specimens that were taken there failed to survive, perhaps because it was a very delicate puppy or because it was acclimatized to the tropical atmosphere of the island.

One of the oldest testimonies of the presence of the Havana whity in Cuba can be found in a painting that belongs to the National Museum of Fine Arts, the work of the famous portrait painter of the wealthy classes of the 18th century, the Cuban Vicente Escobar. In the painting, which is titled Retrato de una joven and dates from 1797, a girl appears with a whity in her arms.

Other graphic testimonies, although not Cuban, are found in European paintings and engravings, and in some treatises from the 18th and 19th centuries dedicated to dogs.

But time goes by, life goes on, and fashions, tastes and human interests change, as do dog breeds, since breeders and dog lovers always seek to improve or modify them according to their preferences, sometimes crossing them. And this was the case of the whity, which was mixed with other breeds of a similar type and thus gave way to the Havanese, which is a slightly larger dog (maximum 27 cm at the withers) and which can currently come in any color, although in the past it was predominantly white or light cream — never the color of a cigar, as many like to repeat.

The whity, for its part, became extinct in Cuba over time, although even in the first decades of the 20th century, the occasional specimen could be seen in Havana, like this one in the photo, which dates from 1927.

As for the Havanese, with the founding of the Republic at the beginning of the last century, the modernization of the country and the modification of old customs, among them, the change in canine fashions, ended up evicted from aristocratic homes — which opted for foreign breeds in vogue — and spontaneously adopted by “ordinary” Cubans, who knew nothing of fine dogs, but who continued to reproduce and preserve them to their liking and good understanding.

Starting in 1990, however, this Cuban dog breed that had been somewhat forgotten experienced a true renaissance. Its breeding was organized, a club was founded to guarantee its conservation and development and, in this way, in a few years, the Havanese once again prospered in its native country.

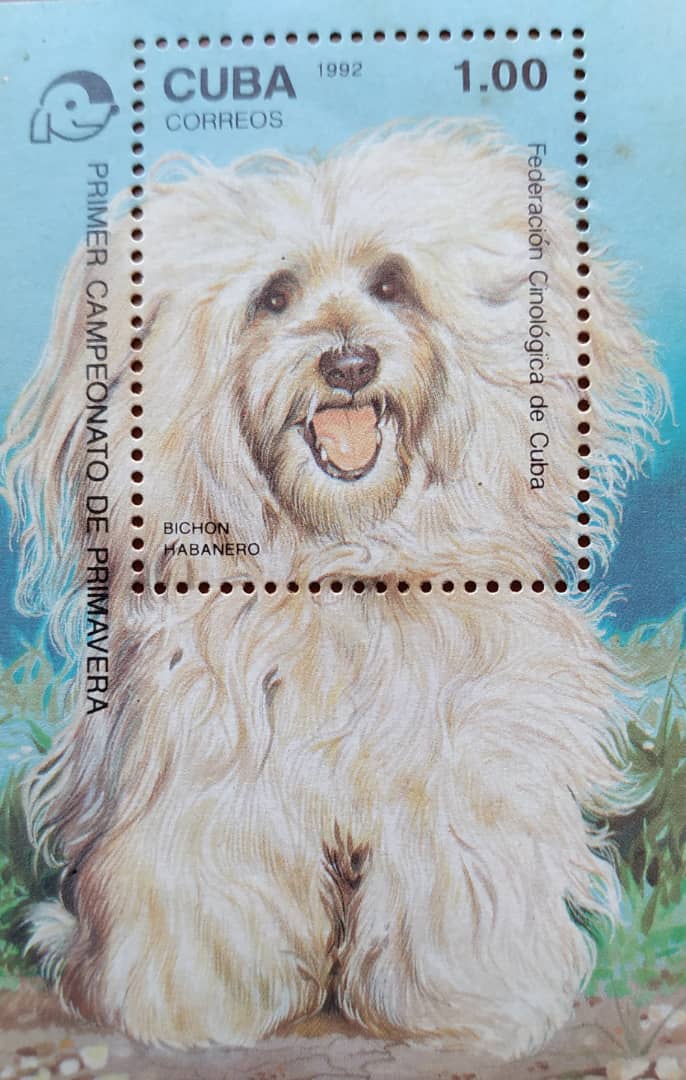

For the first time it competed in the national exhibition tracks with excellent results and in 1993 the first Cuban champions climbed to the podium. It could be said that it was its golden age in Cuba. In 1992, the Ministry of Communications even dedicated a postage stamp to it as part of a collection celebrating the creation of the Cuban Dog Federation and its 7 founding clubs.

It was also around this time that it began to be known throughout the world and its demand increased, which was not exactly good news because it began to be exported en masse and indiscriminately, and not enough specimens were left on the island to guarantee the preservation of the breed. However, its fame and appreciation in the international canine circuits have continued and the population of this breed continued to increase over time.

Today not too many Havanese are seen in Cuba because other breeds have become fashionable and also because dogs, like other cultural and heritage values, are affected by the crises and ups and downs of life and history, and this Cuban breed has certainly had to experience difficult stages.

Even so, there are still some hard-working local breeders who, aware of the valuable cultural and heritage treasure they have in their hands, continue to bet on it. Meanwhile, the Havanese shines in the world with its own lights, standing out in the most important exhibition circuits, winning prizes and the admiration of all those dog lovers who recognize its extraordinary qualities of empathy, charm, good character, sweet heartedness and affectionateness.