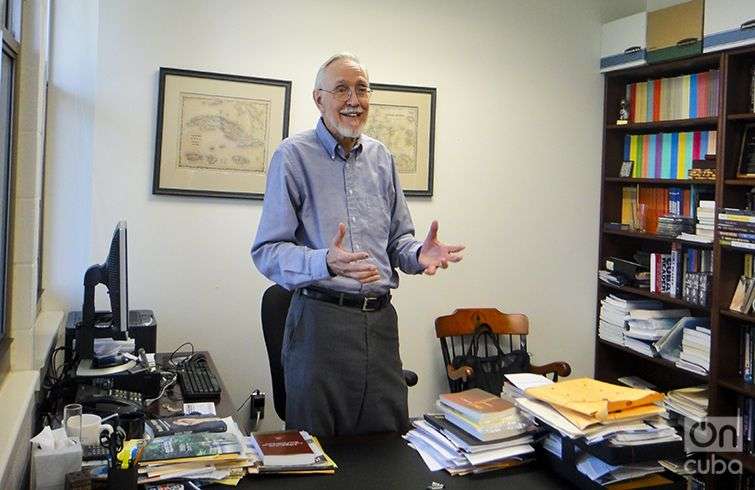

On the beautiful campus of American University in Washington, Prof. William LeogGrande, PhD awaited me. This political scientist has devoted many years of study to Latin American politics and U.S. relations with the rest of the hemisphere.

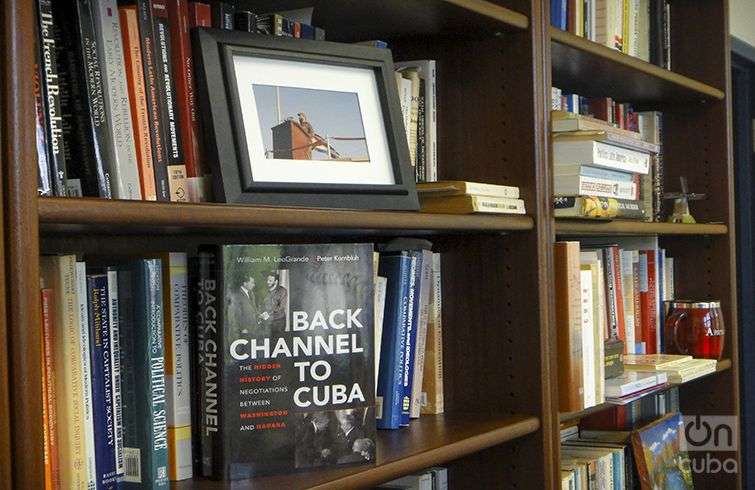

He has been an advisor on these issues for private and government agencies, and is known as one of the most important scholars on U.S.-Cuba relations. His most recent book, Back Channel to Cuba, co-authored with Peter Kornbluh, is an investigation of secret negotiations between the United States and Cuba, a project that he began 20 years ago, he says.

You are a very knowledgeable observer of Cuba. What do you think has changed on the island?

Since the [Communist] Party Congress in 2011, the changes in the economy have been profound. The process is moving slowly, but the nature of the changes to the model are very profound. To me the most important is the recognition that the private sector will now be a permanent and dynamic part of the economy, and also the reliance increasingly on cooperatives as another form of social property, so that the State isn’t trying to manage small and medium-size businesses, but allows the people who work in those businesses to manage them for themselves, and the State restricting itself to larger, strategic industry and enterprise. I think that it’s very difficult if not impossible to centrally plan an economy all the way down to the corner grocery store and the Cuban experience, and the experience of the other socialist countries, demonstrates the difficulty of doing it.

And there’s a sector of the Cuban population that is economically at risk: elderly people on a fixed pension; single mothers trying to provide for their whole family; and to some extent Afro-Cubans because they don’t have relatives abroad to give them remittances, they don’t live in neighborhoods where they can open a paladar, they don’t live in houses where they can rent a room to tourists, so they don’t have access to the hard-currency sector of the economy in the way that other people do. So, I think the challenge for the Cuban State as it tries to raise productivity by using markets is to also find a way to cushion the impact of those changes on the sectors of the population that are most at risk.

Based on this scenario, why has U.S. policy toward Cuba changed?

I think there are two main reasons. One was pressure from…the Latin American presidents at the 6th Summit of the Americas in Cartagena [where] Cuba had not been allowed to participate. Second issue, I think, was the political changes in Miami…. Not only the changes in opinion polls, but also the fact that President Obama himself won half of the Cuban-American vote in 2012. And so, if the Cuban-American community was no longer this homogeneous, conservative community, then a president could take the risk, politically, of changing policy toward Cuba and not think that “I’ve lost Florida for the next election.”

Those two things together were very important. But also, one has to give President Obama credit. He recognized that the old policy didn’t make sense anymore and he wanted to change it. He said in his campaign in 2008 that he wanted to change the policy, and I think it took him six years to do it really because of the domestic political issue in the United States, and also because the issue of Alan Gross became this big obstacle in the road…. So it was a matter of trying to find a way to resolve that obstacle that would clear the road to change

If the next U.S. president is a Republican, do you think he or she would reverse the new policy, which is based on the president’s executive power?

From a legal point of view, a Republican president could reverse everything, because everything Obama has done, he’s done with his presidential authority. But for the diplomatic reason, I don’t think a Republican would. Jeb Bush was asked would he break diplomatic relations with Cuba if he were elected. And he said, “Well, probably. But I haven’t given it a lot of thought.” Now of course Rubio and Cruz said, “Oh, we’d break relations immediately.” But Jeb Bush understands better, I think, than they do what the impact on Latin America would be to do that; it would be a disaster for U.S. relations with the hemisphere. And I think the other thing is, as the policy becomes more and more successful—more people traveling to Cuba, more cooperation in areas like law enforcement and counter-narcotics; the more constituencies in favor of the policy are being created, and therefore it becomes politically more difficult to just reverse everything. What would happen…with a Republican president is not that they would try to roll back things, but they would stop the forward progress.

Cuba is not a major market for the United States. Why is the business sector so interested now?

The fact that Cuba is a small market is one of the reasons that the business sector has not been more active until now. But the other reason is that because the policy of the United States government was so hostile toward Cuba, business people didn’t want to expend the time and the energy, either exploring opportunities or fighting a battle with the government to try to change the policy. But now that the president has changed the policy, and is calling for an end to the embargo, now the business opportunity, even though it’s small, still, it looks much more immediate—it looks like it may be right around the corner. And so businesses are beginning to think about how they could take advantage of the Cuban market. It is a small market, and yet, at the same time, it’s not insignificant. You know, Cuba a few years ago was buying half a billion dollars’ worth of food from the United States. Cuba buys two billion dollars’ worth of food on the world market; most of that could be sold by the United States if there were credit available. Cubans like American products, they’re familiar with American products, and there are lots of basic consumer goods that Cubans would love to have access to from the United States if they could. Cuba is a poor country, but with the lifting of the embargo and an increase in tourists from the United States, that revenue then will become available for Cuba to buy things from the United States. There’s a possibility that trade would be significant—not enormous, but significant.

How does this new policy affect Cuban society?

If we assume that the embargo will, in fact, be lifted in the relatively near future…then I think the economic opportunity for Cuba is substantial. A lot more tourists will go visit Cuba from the United States; that will provide Cuba with revenue that it will be able to buy things from the United States. U.S. investors will go to Cuba, many of them Cuban-Americans who left Cuba many years ago and have been successful in the United States and would like to go back, like the Fanjuls, the Bacardi family. So I think it will be of benefit to the Cuban economy and to the standard of living of the Cuban people.

What’s interesting is how the politics of this plays out inside Cuba. With the United States no longer pursuing a policy of coercion and hostility, the Cuban government has less reason to restrict the civil liberties of its citizens. The argument has always been that there couldn’t be any disunity because of the threat from the United States, an argument that goes all the way back to José Martí. Now, if the threat from United States is diminished then there’s less reason to limit the kind of debate that people can have and even disagreements, not just about particular policies, but disagreements over even who’s in the government and who’s not. So I think that’ll be an interesting process I think we can already see in Cuba: people pushing at the boundaries of debate, and wanting to have more open debate, and insisting on more open debate and in fact having more open debate through a variety of different venues.

Do you foresee any changes to U.S. migration policy on Cuba? Will the Cuban Adjustment Act be overturned?

No, the Administration has been very clear that they’re not willing to change the Cuban Adjustment Act. I think they are afraid…it will set off a migration crisis. And part of the reason is because after December 17th, there was a big surge of people getting on rafts and boats and trying to come to the United States for fear that the Adjustment Act might go away. So they were very quick to say “No, we’re not going to review the Cuban Adjustment Act.” Now, in the longer run if Cuba and the United States have normal relations, it really does not make sense anymore to have this unique status for Cuban immigrants. So I think eventually it will change, but not in the immediate future.

Five to 10 years from now, how you see the U.S.-Cuba situation, taking into account two assumptions—normal, or more normal, relations, and a profound change in leadership?

For the United States, Fidel Castro was a symbol of Cuba’s defiance. And so, with Fidel Castro as the leader of the Revolution it was emotionally hard for the United States to change its policy. I think that’s less true with Raúl Castro in the presidency, but his last name is still Castro, so it’s still an emotional problem for the United States. After 2018, it’s very likely that the president of Cuba will not be named Castro, and…it’ll be a new generation of people born since the Revolution. And it’s important to recognize in the United States we will also have a new generation of people, both in leadership positions in government but also in Miami. Ten years from now there won’t be many people left who came to the United States in 1960, or even in 1970. And so I think a lot of the deep emotions from 1959, 1960, 1961, that have made it so hard for the two countries to get back together, a lot of those will be gone with a new generation that doesn’t remember those battles. You know President Obama himself has said on several occasions, “These are fights that started before I was born. And I’m not interested in revisiting those; I want to look to the future.” And I think 10 years from now we will be in the future.