Milagros has never touched her youngest grandson, even though she sees him once a week. The baby is a year old and lives in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. His grandmother lives in Nogales too, but on the other side of the northern border, in Arizona. Her daughter travels half an hour to the border with the United States, and shows her mother Dario in her arms.

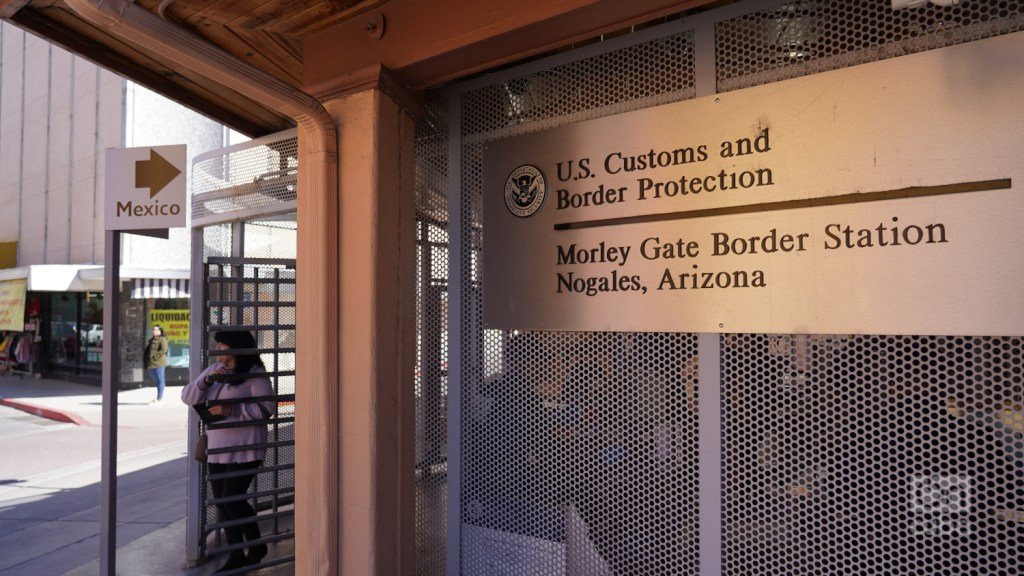

There is another reason for this border fence crossing encounter. Milagros’ eldest grandson is also Mexican, but he studies in the United States. He stays during the week with his undocumented grandmother, and every Friday she takes him from school and brings him to the Morley Gate transit point, where tens of thousands of people come and go every day.

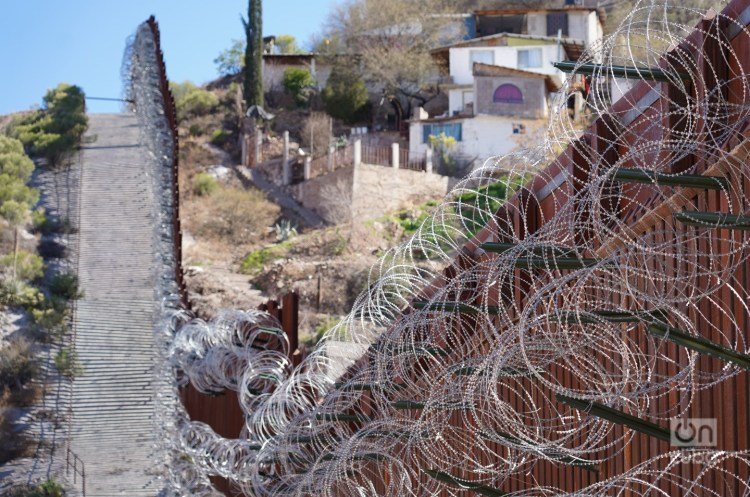

Like other border cities, both Nogales, Sonora and Nogales, Arizona are trafficking channels: drugs to the north, weapons to the south; despite attempts to reinforce and add security to the fence, that technically is not the wall that President Donald Trump likes to announce on television.

Until 2011 it was a precarious fence that separated the community along the 3.6 mile long stretch. Before that, it used to be an ordinary fence. Historically, the two cities have had more in common than toponymy and illicit traffic. Still today there are lives divided, people sleeping on one side, but going to work on the other; earning on one side the bread they will eat under another flag, at a table of bilingual families.

Milagros entered the United States about a year ago, with a tourist visa. She did not return to Mexico when it expired. For the past seven years, visa overstayers have accounted for the highest percentage of the increase in undocumented immigrants in the United States, above illegal entries through the border. But it is easier to control territorial boundaries than the hidden plans of those who enter through an airport or by land, but with a visa.

If Milagros went to Mexico now, she could not come back to Arizona, where she works and can take care of her Mexican grandson who goes to a school in English. She lives illegally in the United States, hoping to eventually be able to regularize her status, also considering the possibility of having to return: “If they deport me, then that’s it.”

In fiscal year 2019, 267,258 people were deported, more than 11,000 in relation to 256,085 in 2018. Five thousand and seven hundred of them were members of “family units”: an increase of 110 percent compared to the previous year.

“He can cross because he is a citizen [of the United States].” The roughly 8-year-old boy kisses her before walking towards the pedestrian control. He crosses alone, under the gaze of his grandmother on one side, and his mother on the other.

From outside the crossing point, officers can be heard calling “Next!” In a couple of minutes someone will be out. On foot and with papers, the process is quite expeditious. At other crossing points, such as Tijuana-San Ysidro or Agua Prieta-Douglas, long lines of cars can wait for hours to enter the United States. When the direction is the opposite, towards the south, the controls are less strict and everything happens faster.

In this part of the Nogales dividing line, the check does not seem more complex than that of any installation; the difference is that instead of a museum or an administrative building, you enter another country.

***

Two Mexican Jehovah’s Witnesses talk in a park in the center of Nogales, Ariz. I interrupt to ask them how they perceive the reduction of migrants in the city. Since January, those who had requested asylum in the United States and waited in Nogales for their appointment in court, were sent to Mexico under a protocol signed in 2018 by the two governments.

The Migrant Protection Protocol (MPP), also called “Remain in Mexico” and questioned by several human rights organizations, has displaced thousands of asylum seekers south of the border.

The last few months so many Cubans have passed, that Elena identifies my accent. Carlos Reyes gave directions to two of them, with a girl, looking for an office, he tells me. “Two countrywomen of yours. They were on the other side. ”

Reyes works in the United States, but he sleeps in his Mexican home every night. He is one of the thousands that increase the population of this American city every day. The police chief, Roy Bermudez, describes a typical scene: “If you pass and walk at night, you will see everything empty, after having seen it full during the day, and you say: what happened here?! ”

In Nogales, he says, they have “neither more or less problems with drugs than any border city.” That is, many. The illicit traffic in narcotic drugs across the border between Mexico and the United States is estimated at around 500 billion dollars.

They throw the drugs in soccer ball-sized packages above the fence or mules carry it on their backs crossing areas where there is poor immigration control, explains Bermudez, clarifying that the controllers are not themselves but Customs and Border Protection (CBP). In recent years, authorities have discovered hundreds of narco tunnels to supply their products to the US market, which is the destination for a quarter of all world consumption.

“If they make a higher fence, they will build taller ladders. And if they can’t get over, they will do it underground, ” Bermudez predicts.

***

Milagros’ grandson, already in Nogales, Sonora, runs to greet his mother and brother, and joins the cross-border conversation.

“Tell him, grandma, how I behaved,” he asks on the other side of the fenced wall, seeking approval from the mother, who has not been with him for days. “Yes, very good. And he has homework!” Milagros warns. She is a grandmother who gives back her grandson with an update and instructions, as they usually do when they live in the same neighborhood of their children, or the same city. Now it is from the United States to Mexico, even it’s a meter away.